2024-09-0514:01

Status:CPSC110

Tags: Computer Science Systematic design process

Introduction

The major goal of this course is to introduce students to a systematic method for solving hard design problems. Going forward in your career you will of course learn additional techniques, but the design method covered in CPSC 110 will serve you well whenever you face a difficult design problem — whether it is program design or a problem from another field entirely.

Course Principles

- Systematic Design Process

This is demonstrated by being able to write programs for a reasonably complex task, where the ability to use the “one task - one function” rule can be demonstrated.

- Readability

This is demonstrated by being able to write code that is readable, well organized, documented, and tested.

- Relationship Between Information and Data

This is demonstrated by being able to design the data representation for a reasonably complex problem, and to describe the information encoded in the given data.

- Relationship Between Data Structure and Program Structure

This is demonstrated by being able to identify correspondences between a data definition and a program that operates on that data. Also by being able to identify how potential changes to a data definition would affect a program.

- Abstraction and Reduction of Redundancies

This is demonstrated by being able to produce examples of code before and after abstraction: before, where one can see the repeated code, and after, where one can see the abstraction and verify that it provides the solution to the original problem, as well as several other similar problems. Students should also be able to design a program that uses existing libraries or existing code to solve a new problem.

- Alternative Notation to Describe Code

This is demonstrated by being able to identify correspondences between non-code models of a program and the program itself and by being able to use non-code models in program design.

BSL (Beginning Student Language)

Documentation: https://docs.racket-lang.org/htdp-langs/beginner.html#%28def._htdp-beginner._%28%28lib._lang%2Fhtdp-beginner..rkt%29._exp%29%29

Common Arithmetic Expressions

Syntax: there must be a space separating the operator e.g. ’+’, and the integer values, ‘x,’ ‘y,’ ‘z’. These expressions can be complex, and thus follow the general order of operations: Brackets → Exponents → Multiplication (Division = sequential as division can be ) → Addition (Subtraction = negative addition)

;; Addition

(+ x y z ...)

;; Subtraction

(- x y z ...)

;; Multiplication

(* x y z ...)

;; Division

(/ x y z ...)

;; Power/exponent

(expt x y)

;; Mod

(modulo x y)

;; Complex expressions (follows BEDMAS) - USE BRACKETS

(* (+ 3 4) (+ 1 1))Primitive Calls

A primitive call is a basic expression often built into the programming language: Arithmetic expressions are primitive calls, where the operation symbol is the operator, and the values x, y, and z are the operands. To evaluate a primitive call: Operand = anything operated on e.g. 3 + x Parameter = the placeholder variable in defining a function e.g. pow(x) Argument = the value that goes into the function e.g. x = 3 pow(3)

- First reduce operands to values: e.g.

(+ 1 2)3 - The apply primitive to the values: e.g.

(+ (+ 1 2) + 1)(+ 3 1)4 E.g.

(+ 2 (*3 4) (- (+ 1 2) 3))

= (+ 2 12 (- (+ 1 2) 3))

= (+ 2 12 (-3 3))

= (+ 2 12 0)

= 14 This is similar to BFS.

Strings in BSL

Other kinds of primitives include images and strings. Some sample functions for strings include:

(string-append "Ada" " " "Lovelace") ;; ""

(string-length "apple") ;; "5"

(substring "Caribou" 2 4) ;; "ri"

(substring "Caribou" 0 3) ;; "Car"Images in BSL

Defining shapes, images, and textual images

(require 2htdp/image)

(circle {radius} {"texture"} {"colour"})

(rectangle {width} {length} {"texture"} {"colour"})

(text {"messgae"} {font size} {"colour"}) ;; image of the "message"

;; etc. Calls

above ((image ... ) (image ... ) ... ) ;; stacks images on top of each other

beside ((image ... ) (image ... ) ... );; puts images next to each other

overlay ((image ... ) (image ... ) ... );; superimposes images

rotate ({degree} {image}) ;; rotates images

;; etc. Constant Definitions offer readability, changeability, and brevity to a program.

To form a constant definition, use the following: (define <name> <expression>)

(require 2htdp/image)

(define WIDTH 400) ;; constants are typically capitalized

(define HEIGHT 600)

(* WIDTH HEIGHT) ;; = (* 400 HEIGHT) = (400 600)You can straight up copy images from Google and paste them into the IDE to define them

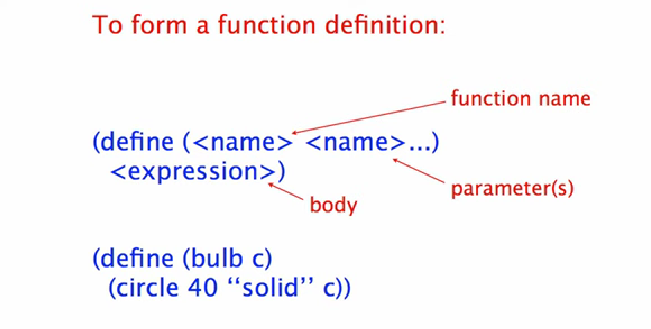

Function Definitions

In order to reduce repetition, functions are used. E.g. f(x). Operand = anything operated on e.g. 3 + x Parameter = the placeholder variable in defining a function e.g. pow(x) Argument = the value that goes into the function e.g. x = 3 pow(3)

Defining a function:

(require 2htdp/image)

(define (bulb c) ;; whitespace does not matter

(circle 40 "solid" c))

(above (bulb "red")

(bulb "yellow")

(bulb "green"))

This follows the same order of precedence for operation calls

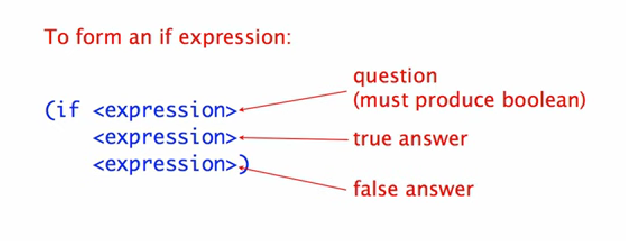

Boolean and Conditional Expressions

Predicates are values that return boolean values.

Another way of expressing conditionals is by using the following syntax:

Predicates are values that return boolean values.

Another way of expressing conditionals is by using the following syntax:

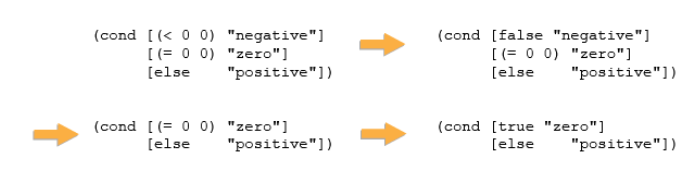

(cond [(> 1 2) "bigger"]

[(= 1 2) "equal"]

[(< 1 2) "smaller"])

;; Which evaluates to...

(cond [false "bigger"]

[(= 1 2) "equal"]

[(< 1 2) "smaller"])

(cond [(= 1 2) "equal"]

[(< 1 2) "smaller"])

(cond [false "equal"]

[(< 1 2) "smaller"])

(cond [(< 1 2) "smaller"])

(cond [true "smaller"])

"smaller"

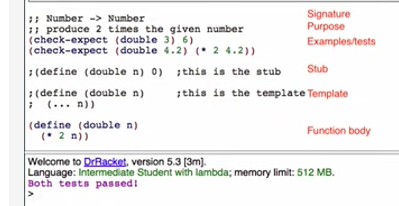

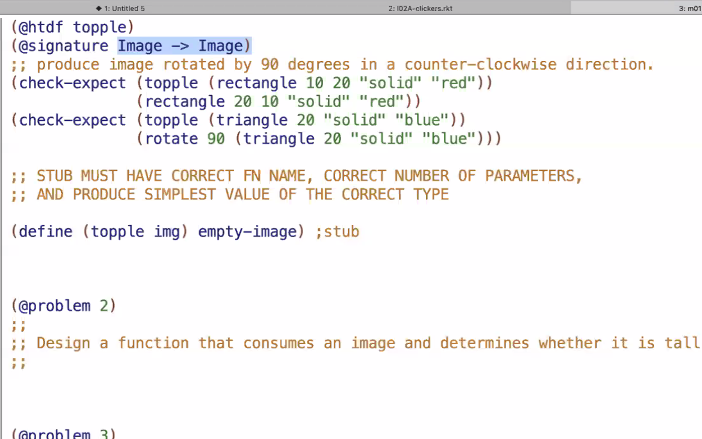

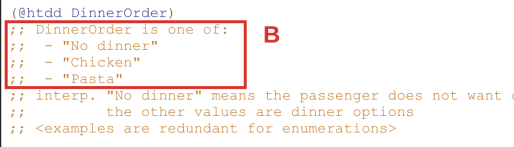

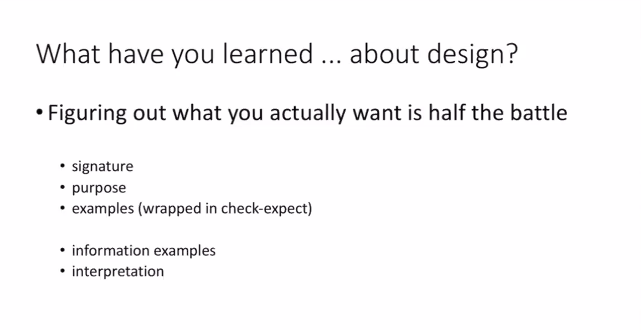

How to Design Functions (HtDF)

Heavily referenced https://cs110.students.cs.ubc.ca/reference/design-recipes.html#HtDF for information

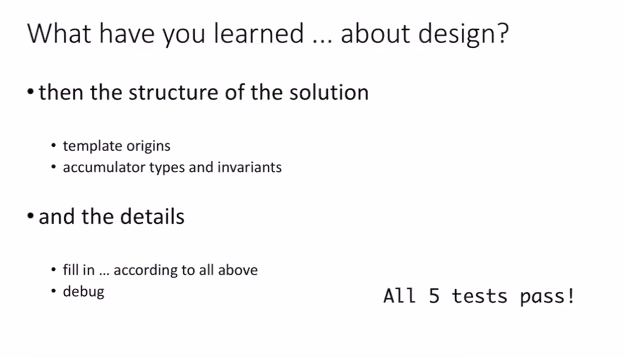

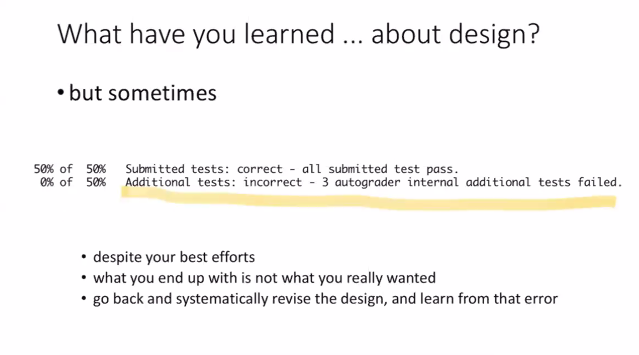

The How to Design Functions (HtDF) recipe is a design method that enables systematic design of functions. We will use this recipe throughout the term, although we will enhance it as we go to solve more complex problems.

Signatures help write purpose. The stub and the check-expects help code the body. = The template is meant to be an aid. Doing the steps in another order is permissible if it helps (however, you should never write a function definition first and then the other elements as that defeats the point of writing with a template + it introduces new errors). A general rule of thumb is to “run early and run often.”

- Signature, purpose, stub

- The entire function starts with an

@htdftag. This indicates the name of the function, and the fact that what follows is going to be designed in accordance with the design template. - Signatures take the form of `@signature … →

- Purpose statements should be one line statements explaining the ONE purpose of a function (must be <80 characters).

- The stub is a “dummy line” that is syntactically complete and produces a “dummy value.” This is so the check-expects can run without need for fully developed code: E.g.

(define (double n) 0) ; this is the stub

- The entire function starts with an

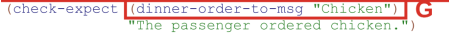

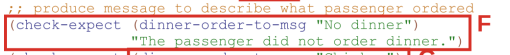

- Examples (wrapped in check-except)

- Check expects act as test cases that indicate whether a function behaves as it should. For instance, suppose a function should double a value:

(double 0) should produce 0,(double 1) should produce 2, and(double 2) should produce 4. - Replace “should produce” with another bracket expression that shows how the desired function should operate to produce that value:

(check-expect (double 0) (* 0 2)),(check-expect (double 1) (* 1 2)), and `(check-expect (double 3) (* 3 2)) - Check expects should always handle the edge cases and cover a base case of the function. A common example is when a function is evaluating if a number is greater than a value, it should check one above, one below and at the value. The cases passed only needs to make sense to the problem: so having a negative length of a square as a test case would not be necessary (this will be further discussed in HtDD).

- On check-expect: Must test 1 above and 1 below target: e.g. if a function is seeing if an image is taller than 20, heights of 19, 20, and 21 must be tested. Also consider fringe cases at 0, out of bounds numbers, null values etc.

- Check expects act as test cases that indicate whether a function behaves as it should. For instance, suppose a function should double a value:

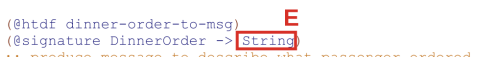

- Inventory - template and constants

- The template is the basic structure of a function. Templates will be designed in accordance to how data is structured (according to HtDD).

@template-originis the first input data type. (i.e. if the function takes one image and one number the template-origin should be(@template-origin Image).- The template should be copied from the design recipe defined earlier in the code. Here is an example with the definition outside the template:

(@template

(define (double n) ;this a copy of the template for reference

(... n)))

(define (double n) ;this is the start of the final function definition

(... n))

- Code body

- Now complete the function body by using the information in the previous steps.

- The signature tells you the type of the parameter(s) and the type of the data the function body must produce

- The purpose describes what the function body must produce in English

- The examples provide several concrete examples of what the function body must produce

- The template tells you the basic function structure - the raw material you have to work with

- Now complete the function body by using the information in the previous steps.

- Test and debug

- -The signature tells you the type of the parameter(s) and the type of the data the function body must produce

- The purpose describes what the function body must produce in English

- The examples provide several concrete examples of what the function body must produce

- The template tells you the basic function structure - the raw material you have to work with

Full Template and Example

(@htdf foo)

(@signiature <Type> <Type> ... -> <Type>)

;;Description of function (brief)

(check-expect (foo x y ...) <expected value>)

(check-expect (foo x y ...) <expected value>)

; (define (foo x y ...) <temp value>) ; this is a stub

(@template

(define (foo x y ...)

(... x y ) )

(define (foo x y ...)

(<code body here>))

``````bsl

(@signature Number -> Number)

;; Purpose: given a side length of a square, calculates the area of the sqaure

(check-expect (area 2) 4)

(check-expect (area 1.1) 1.21)

(check-expect (area 0) 0)

;(define (area n) 0);stub

(@template

(define (area n)

(... n)))

(define(area n)

(* n n))Further Examples

]

]

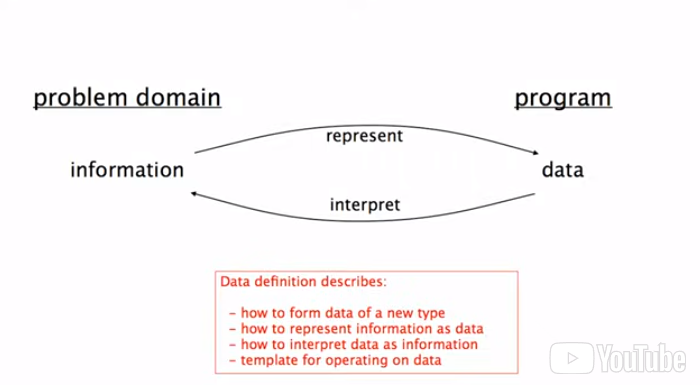

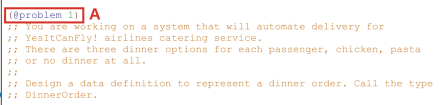

How to Design Data (HtDD)

Heavily referenced : https://cs110.students.cs.ubc.ca/reference/design-recipes.html#HtDF

Data definitions will describe how we are representing/interpreting information as data. Data in the program can be interpreted as information in the program’s domain.

A data definition must describe how to form data that satisfies the data definition and if the data meets those requirements. E.g. (define velocities = [19, -20, 0]) data must be formed as an integer, and if an element like "apple" was added there should be an error signifying that it does not follow the data definition. Additionally, if “velocities” wasn’t added those numbers could quantify anything.

The structure of the information in the program’s domain determines the kind of data definition used, which in turn determines the structure of the data-driven templates and helps determine the function examples (check-expects), and therefore the structure of much of the final program design.

After the (@htdd) tag, take the following steps where applicable.

- A possible structure definition (not until compound data)

- The structure of the information in the program’s domain determined the kind of data definition used.

- The type/organization of the data determines the template used and the nature of the

(check-expect)s.

Data Definitions (more in depth later on)

The general form of a data definition is as follows:

(@htdd Dataset)

;; Dataset is <Data Type> ; similar to signature in htdf

;; interp. data inside of set ; brief interpretation of the data, similar to purpose

(define D1 <x>) ;test value 1 ; examples of data types (may be redundant for specific data types)

(define D2 <y>) ;test value 2

(define D3 <z>) ;test value 3

; ...

(@dd-template-rules <rules used> ; e.g atomic-distinct, atomic-non-disticnt

<rules used>

<rules used>

... )

(deine (fn-for-Dataset d) ; format depends on the type of data passsed + will be copied as the template for htdf

(... d))

| When the form of the information to be represented… | Use a data definition of this kind |

|---|---|

| is atomic | Simple Atomic Data |

| is numbers within a certain range | Interval |

| consists of a fixed number of distinct items | Enumeration |

| is comprised of 2 or more subclasses, at least one of which is not a distinct item | Itemization |

| consists of two or more items that naturally belong together | Compound data |

| is naturally composed of different parts | References to other defined type |

| is of arbitrary (unknown) size | Self-referential or mutually referential |

Custom Data

Simple Atomic Data:

Use simple atomic data when the information to be represented is itself atomic in form, such as the elapsed time since the start of the animation, the x coordinate of a car or the name of a cat.

2 check-expects are needed

(@htdd Time)

;; Time is Natural

;; interp. number of clock ticks since start of game

(define START-TIME 0)

(define OLD-TIME 1000)

(@dd-template-rules atomic-non-distinct) ;Natural

(define (fn-for-time t)

(... t))

Intervals

A special case of the number types (Number, Integer, and Natural) arises when the information to be represented is numbers within a certain range. In an interval data definition describe the bounds of the interval as part of the interpretation. For example, integers in the range [0, 10]. In specifying the bounds use the notation that [ and ] mean that the end of the interval includes the end point; ( and ) mean that the end of the interval does not include the end point. So [0, 10] is 0 to 10 inclusive; [0, 10)0 inclusive to 10 exclusive.

(@htdd Countdown)

;; Countdown is Integer

;; interp. the number of seconds remaining to liftoff, restricted to [0, 10]

(define C1 10) ; start

(define C2 5) ; middle

(define C3 0) ; end

(@dd-template-rules atomic-non-distinct) ;Integer

(define (fn-for-countdown cd)

(... cd))

For data examples provide sufficient examples to illustrate how the type represents information. The three data examples above are probably more than is needed in this case.

When writing tests for functions operating on intervals be sure to test closed boundaries as well as points off the boundary such as midpoints. As always, be sure to include enough tests to check all other points of variance in behavior across the interval.

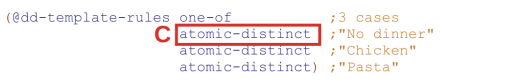

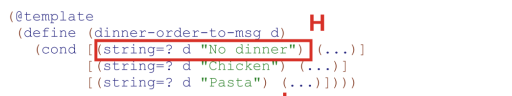

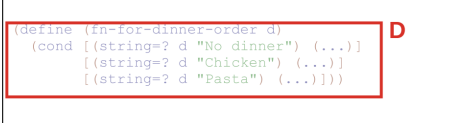

Enumerations

Use an enumeration when the information to be represented consists of a fixed number of distinct items, such as colors, letter grades, provinces etc. The data used to represent an enumeration could in principle be anything - strings, integers, images even. Some languages provide an explicit mechanism rather than allowing arbitrary data selection - we mirror that by always using strings for enumerations. In the case of enumerations it is sometimes redundant to provide an interpretation and nearly always redundant to provide examples.

(@htdd LightState)

;; LightState is one of:

;; - "red"

;; - "yellow"

;; - "green"

;; interp. the color of a traffic light

;; <examples are redundant for enumerations>

(@dd-template-rules one-of ;3 cases

atomic-distinct ;"red"

atomic-distinct ;"yellow"

atomic-distinct) ;"green"

(define (fn-for-light-state ls)

(cond [(string=? ls "red") (...)]

[(string=? ls "yellow") (...)]

[(string=? ls "green") (...)]))

- A

LightStateenumeration is an enumeration with 3 cases, so the one of rule says to use acondwith 3 cases. - Do not use

elseunless the large enumeration rule is used. - Examples are redundant for enumerations

- The order of the question answer pairs in the conditional must match the order of subclasses in the type comment

Large Enumerations

In the cases where an enumeration has numerous elements, a large enumeration is used. For instance marking every possible keyboard press in KeyEvent. It is not necessary to write test cases, just write 2.

Defer writing templates for such large enumerations until a template is needed for a specific function. At that point include the specific cases that particular function cares about. Be sure to include an else clause in the template to handle the other cases. As an example, some functions operating on KeyEvent may only care about the space key and ignore all other keys, the following would be an appropriate template for such functions.

(@template-origin KeyEvent)

(@template

(define (fn-for-key-event kevt)

(cond [(key=? " " kevt) (...)]

[else

(...)])))

The same is true of writing tests for functions operating on large enumerations. All the specially handled cases must be tested, in addition one more test is required to check the else clause.

Itemizations

An itemization describes data comprised of 2 or more subclasses, at least one of which is not a distinct item. (C.f. enumerations, where the subclasses are all distinct items.) In an itemization the template is similar to that for enumerations: a cond with one clause per subclass. In cases where the subclass of data has its own data definition the answer part of the cond clause includes a call to a helper template, in other cases it just includes the parameter.

(@htdd Bird)

;; Bird is one of:

;; - false

;; - Number

;; interp. false means no bird, number is x position of bird

(define B1 false)

(define B2 3)

(@dd-template-rules one-of ;2 cases

atomic-distinct ;false

atomic-non-distinct) ;Number

(define (fn-for-bird b)

(cond [(false? b) (...)]

[else (... b)]))

Note that the order of question/answer pairs in the cond must match the order of subclasses in the type comment. In addition, in any function where the template is used, the cond question/answer pairs must not be re-ordered and the cond questions must not be edited in any way. Except when using the large enumeration rule all cond question/answer pairs must be preserved.

Functions operating on itemization should have at least as many tests as there are cases in the itemizations. If there are intervals in the itemization, then there should be tests at all points of variance in the interval. In the case of adjoining intervals it is critical to test the boundaries.

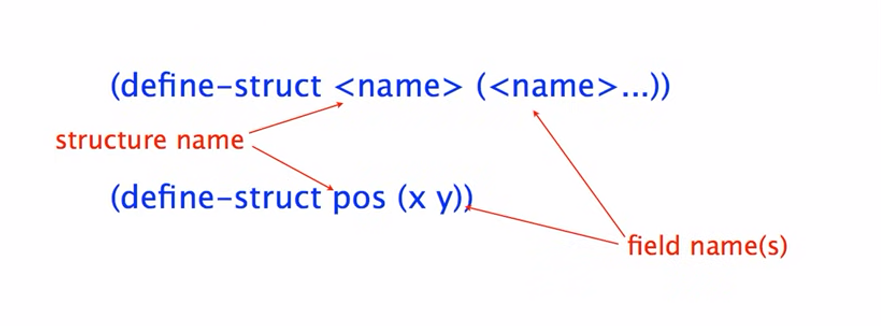

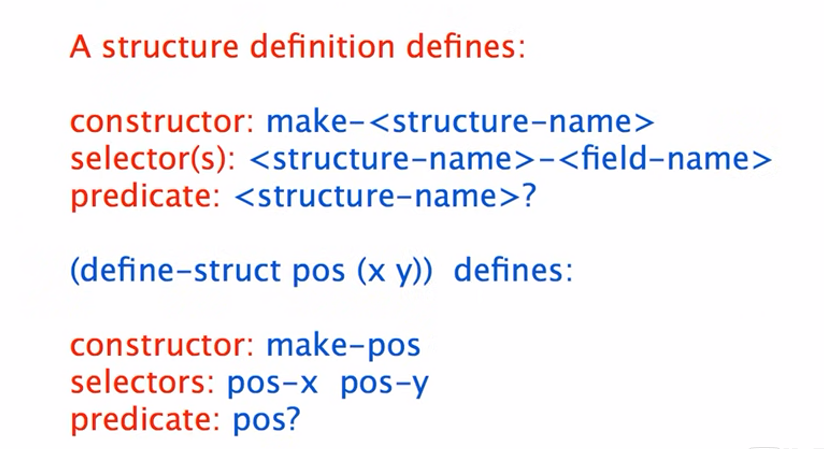

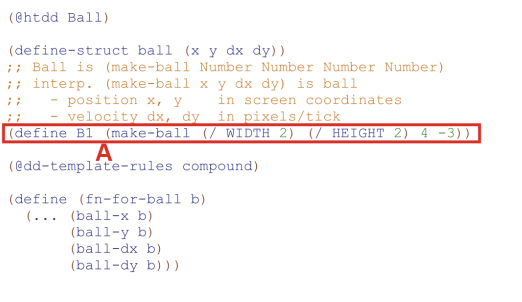

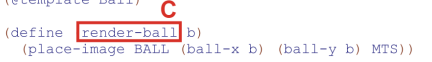

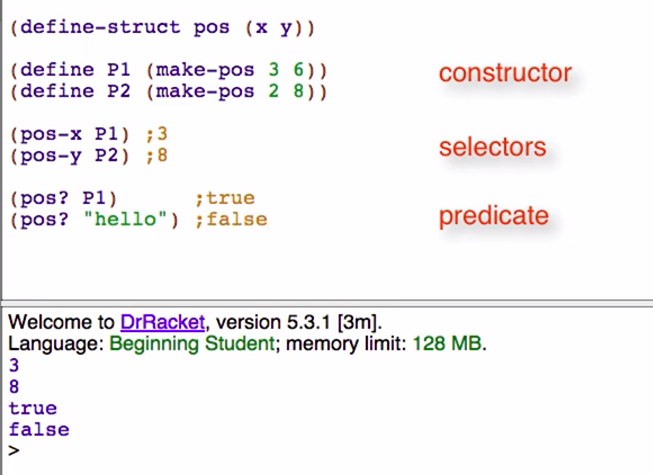

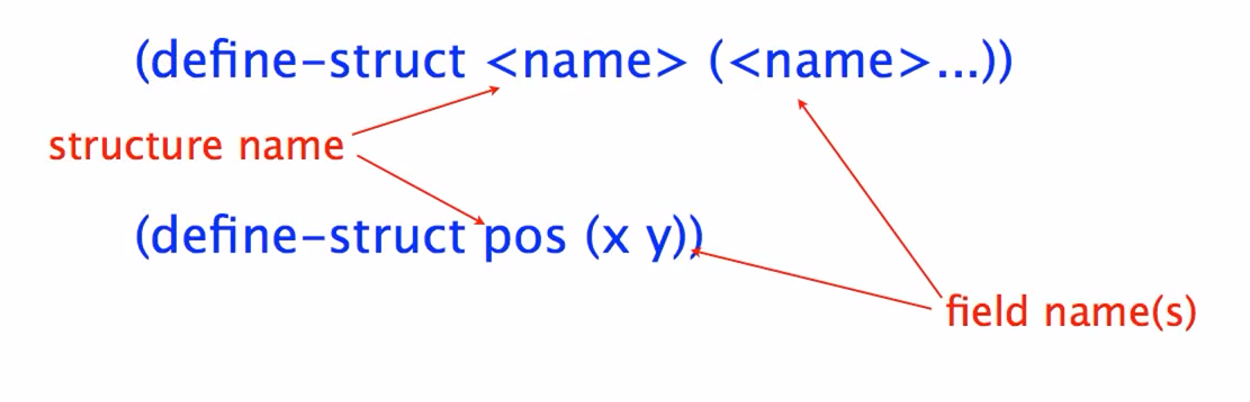

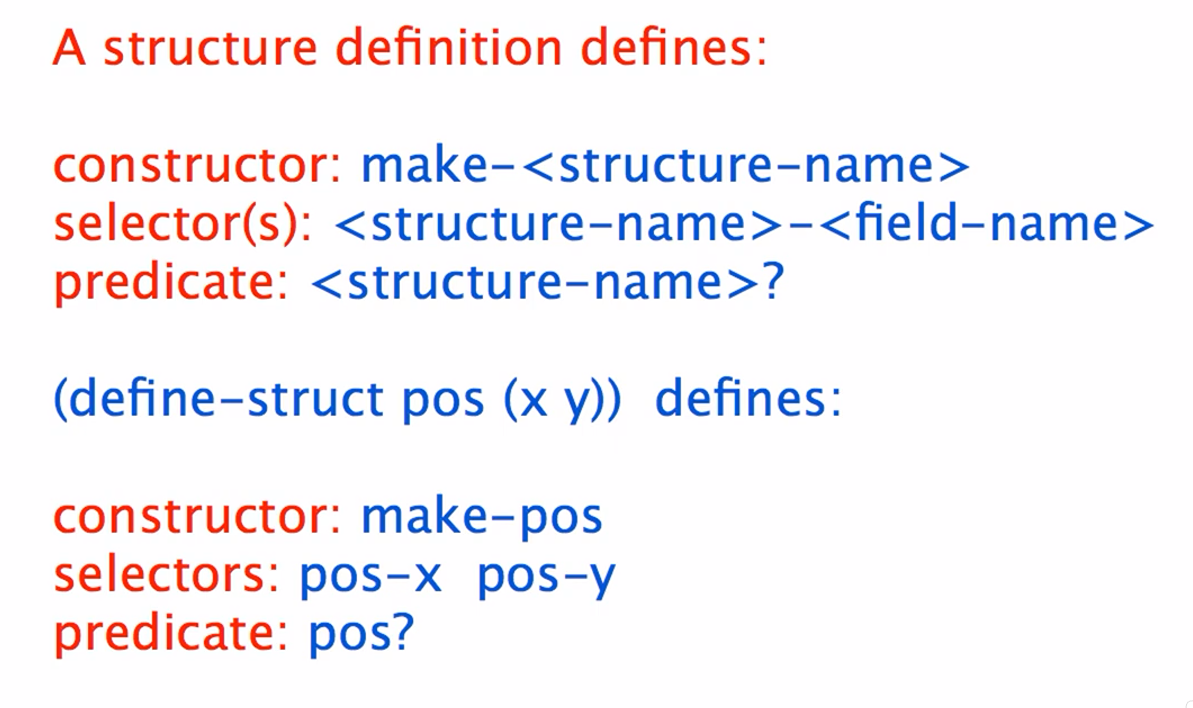

Compound Data

Use compound when two or more values naturally belong together. The define-struct goes immediately after the @htdd tag, and before the type comment.

(@htdd Ball)

(define-struct ball (x y))

;; Ball is (make-ball Number Number)

;; interp. a ball at position x, y

(define BALL-1 (make-ball 6 10))

(@dd-template-rules compound) ;2 fields

(define (fn-for-ball b)

(... (ball-x b) ;Number

(ball-y b))) ;Number

Reference to Other Data Definitions

Some data definitions contain references to other data definitions you have defined (non-primitive data definitions). One common case is for a compound data definition to comprise other named data definitions. (Or, once lists are introduced, for a list to contain elements that are described by another data definition. In these cases the template of the first data definition should contain calls to the second data definition’s template function wherever the second data appears. For example:

--assume Ball is as defined above---

(@htdd Game)

(define-struct game (ball score))

;; Game is (make-game Ball Number)

;; interp. the current state of a game, with the ball and score

(define GAME-1 (make-game (make-ball 1 5) 2))

(@dd-template-rules compound ;2 fields

ref) ;(game-ball g) is Ball

(define (fn-for-game g)

(... (fn-for-ball (game-ball g))

(game-score g))) ;Number

How to Design Worlds (HtDW)

The How to Design Worlds process provides guidance for designing interactive world programs using big-bang. While some elements of the process are tailored to big-bang, the process can also be adapted to the design of other interactive programs. The wish-list technique can be used in any multi-function program.

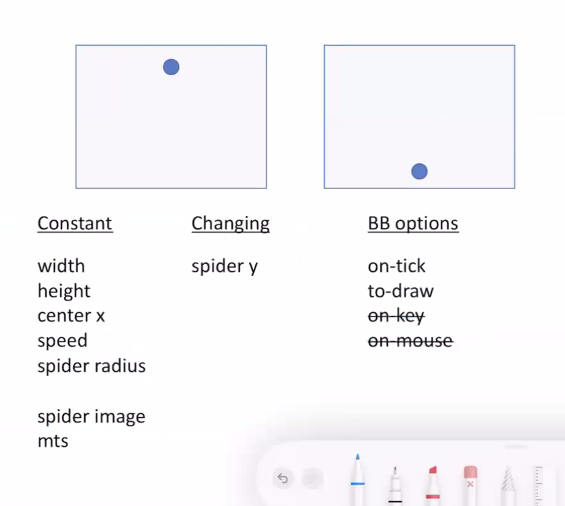

- Domain analysis (use a piece of paper!

- Sketch program scenarios

- Identify constant information

- Identify changing information

- Identify big-bang options

- Build the actual program

Domain Analysis

To analyze a domain, hand draw 3 or more pictures of what the world program will look like at different phases. Then use this photo to identify constant information (e.g. width-screen length WIDTH (constants must be in all caps)), changing information (e.g. y position of a firework), and identification of which big-bang options are needed for the program.

on-tick= program needs to change as time goes on (nearly all do).to-draw= program needs to display something (nearly all do).on-key= program needs to change in response to key presses.on-mouse= program needs to change in response to mouse activity.stop-when= program needs to stop automatically.- (There are more, but these are the only ones needed/used in this course)

Building the Actual Program

There are 4 phases to designing programs:

- Requires followed by one line summary of program’s behavior

- Constants

- Data definitions

- Functions

The program should include libraries before functions are used = “requires” This will be followed by a brief line explaining the program’s function (ideally one line). Then definition of constants, coming directly from the domain analysis. This is followed by data definitions (that describe how the world state (the changing information identified during the analysis). The function section should be the main function which uses big-bang with the appropriate options.

Template for a World Program

(require spd/tags)

(require 2htdp/image)

(require 2htdp/universe)

;; My world program (make this more specific)

(@htdw WS) ;(give WS a better name)

;; =================

;; Constants:

;; =================

;; Data definitions:

(@htdd WS)

;; WS is ...

;; =================

;; Functions:

(@htdf main)

(@signature WS -> WS)

;; start the world with ...

;;

(@template-origin htdw-main)

(define (main ws)

(big-bang ws ; WS

(on-tick tock) ; WS -> WS

(to-draw render) ; WS -> Image

(on-mouse ...) ; WS Integer Integer MouseEvent -> WS

(on-key ...))) ; WS KeyEvent -> WS

(@htdf tock)

(@signature WS -> WS)

;; produce the next ...

;; !!!

(define (tock ws) ws)

(@htdf render)

(@signature WS -> Image)

;; render ...

;; !!!

(define (render ws) empty-image)

Depending on which other big-bang options you are using you would also end up with wish list entries for those handlers. So, at an early stage a world program might look like this:

(require 2htdp/universe)

(require 2htdp/image)

;; A cat that walks across the screen.

(@htdw Cat)

;; Constants:

(define WIDTH 200)

(define HEIGHT 200)

(define CAT-IMG (circle 10 "solid" "red")) ; a not very attractive cat

(define MTS (empty-scene WIDTH HEIGHT))

;; Data definitions:

(@htdd Cat)

;; Cat is Number

;; interp. x coordinate of cat (in screen coordinates)

(define C1 1)

(define C2 30)

(@dd-template-rules atomic-non-distinct)

(define (fn-for-cat c)

(... c))

;; Functions:

(@htdf main)

(@signature Cat -> Cat)

;; start the world with initial state c, for example: (main 0)

(@template-origin htdw-main)

(define (main c)

(big-bang c ; Cat

(on-tick tock) ; Cat -> Cat

(to-draw render))) ; Cat -> Image

(@htdf tock)

(@signature Cat -> Cat)

;; Produce cat at next position

;!!!

(define (tock c) 1) ;stub

(@htdf render)

(@signature Cat -> Image)

;; produce image with CAT-IMG placed on MTS at proper x, y position

; !!!

(define (render c) MTS)

Key and Mouse Handlers

The on-key and on-mouse handler function templates are handled specially. The on-key function is templated according to its second argument, a KeyEvent, using the large enumeration rule. The on-mouse function is templated according to its MouseEvent argument, also using the large enumeration rule. So, for example, for a key handler function that has a special behavior when the space key is pressed but does nothing for any other key event the following would be the template:

(@template-origin KeyEvent)

(@template

(define (handle-key ws ke)

(cond [(key=? ke " ") (... ws)]

[else

(... ws)])))

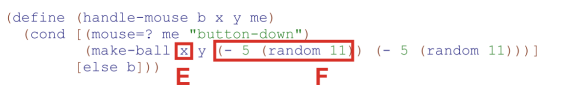

Similarly, the template for a mouse handler function that has special behavior for mouse clicks but ignores all other mouse events would be:

(@template-origin MouseEvent)

(@template

(define (handle-mouse ws x y me)

(cond [(mouse=? me "button-down") (... ws x y)]

[else

(... ws x y)])))

For more information on the KeyEvent and MouseEvent large enumerations see the DrRacket help desk.

Data Driven Templates

Templates are the core structure that we know a function must have, independent of the details of its definition. In many cases the template for a function is determined by the type of data the function consumes. We refer to these as data driven templates. The recipe below can be used to produce a data driven template for any type comment.

For a given type TypeName the data driven template is: an appropriately chosen parameter name (often the initials of the type name) and the body is determined according to the table below. To use the table, start with the type of the parameter, i.e. TypeName, and select the row of the table that matches that type. The first row matches only primitive types, the later rows match parts of type comments.

(define (fn-for-type-name x)

<body>)

Where x is an appropriately chosen parameter name (often the initials of the type name) and the body is determined according to the table below. To use the table, start with the type of the parameter, i.e. TypeName, and select the row of the table that matches that type. The first row matches only primitive types, the later rows match parts of type comments.

| Type of data | cond question (if applicable) | Body or cond answer (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Non-Distinct - Number - String - Boolean - Image - etc. | Appropriate predicate - (number? x) - (string? x) - (boolean? x) - (image? x) - (and (⇐ 0 x) (< x 10)) - etc. | Expression that operates on the parameter. (… x) |

| Atomic Distinct Value - “red” - false - empty - etc. | Appropriate predicate - (string=? x “red”) - (false? x) - (empty? x) - etc. | Since value is distinct, parameter does not appear. (…) |

| One Of - enumerations - itemizations | Cond with one clause per subclass of one of. (cond [ [ Where each question and answer expression is formed by following the rule in the question or answer column of this table for the corresponding case. A detailed derivation of a template for a one-of type appears below. Always use else for the last question for itemizations and large enumerations. Normal enumerations should not use else. Note that in a mixed data itemization, such as ;; Measurement is one of: ;; - “high” ;; - “low” ;; - Number the cond questions must be guarded with an appropriate type predicate. In particular, the first cond question for Measurement must be (and (string? m) (string=? m “high”)) where the call to string? guards the call to string=?. This will protect string=? from ever receiving a number as an argument. | |

| Compound - Position - Firework - Ball - cons - etc. | Predicate from structure - (posn? x) - (firework? x) - (ball? x) - (cons? x) (often just else) - etc. | All selectors. - (… (posn-x x) (posn-y x)) - (… (firework-y x) (firework-color x)) - (… (ball-x x) (ball-dx x)) - (… (first x) (rest x)) - etc. Then consider the result type of each selector call and wrap the accessor expression appropriately using the table with that type. So for example, if after adding all the selectors you have: (… (game-ball g) ;produces Ball (game-paddle g)) ;produces Paddle Then, because both Ball and Paddle are non-primitive types (types that you yourself defined in a data definition) the reference rule (immediately below) says that you should add calls to those types’ template functions as follows: (… (fn-for-ball (game-ball g)) (fn-for-paddle (game-paddle g))) |

| Other Non-Primitive Type Reference | Predicate, usually from structure definition - (firework? x) - (person? x) | Call to other type’s template function - (fn-for-firework x) - (fn-for-person x) |

| Self Reference | Form natural recursion with call to this type’s template function: - (fn-for-los (rest los)) | |

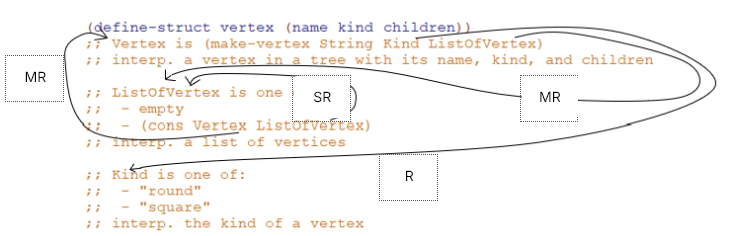

| Mutual Reference Note: form and group all templates in mutual reference cycle together. | Call to other type’s template function: (fn-for-lod (dir-subdirs d) (fn-for-dir (first lod)) | |

| The previous example doesn’t cover the mutual-reference rule, which says that in the case of mutually-referential data definitions, when you template one function in the mutual-reference cycle you should immediately template all the functions in the mutual-reference cycle. So, for example, given: |

(define-struct person (name subs))

;; Person is (make-person String ListOfPerson)

;; ListOfPerson is one of:

;; - empty

;; - (cons Person ListOfPerson)

Then if you need a template for a function operating on a Person (or a function operating on a ListOfPerson) you should immediately write a template for both functions, resulting in something like this:

(define (fn-for-person p)

(... (person-name p)

(fn-for-lop (person-subs p)))) ;mutual recursion from mutual-reference

(define (fn-for-lop lop)

(cond [(empty? lop) ...]

[else

(... (fn-for-person (first lop)) ;mutual recursion from mutual-reference

(fn-for-lop (rest lop)))])) ;natural recursion from self-reference

Midterm 1 Preparation

https://cs110.students.cs.ubc.ca/admin/exam-instructions.html

Terminology

“answer expression” (N/A)

“argument” (N/A)

“atomic distinct” (N/A)

“constant definition” (N/A)

“constant name”  “data example”

“data example”  “dd template rule”

“dd template rule”  “expression” (N/A)

“function body” (N/A)

“function call expression” (F)

“expression” (N/A)

“function body” (N/A)

“function call expression” (F)

“function definition” (N/A)

“function example”

“function definition” (N/A)

“function example”  “function name”

“function name”  “if statement” (N/A)

“metadata annotation”

“if statement” (N/A)

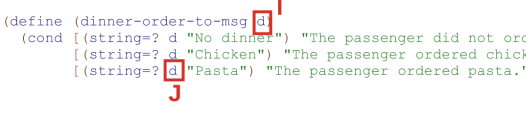

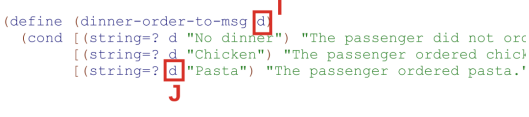

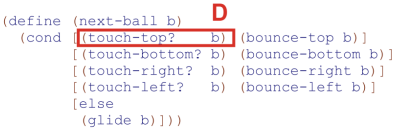

“metadata annotation”  “operand” (J)

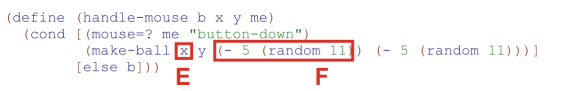

“operand” (J)  “parameter” (E, I)

“parameter” (E, I)

“question expression”

“question expression”

“structure definition” (N/A)

“template” (commented out)

“structure definition” (N/A)

“template” (commented out)  “type comment”

“type comment”  “type name”

“type name”

Compound Data

Self-Reference

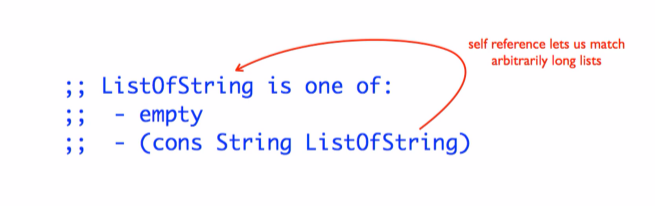

Arbitrary Sized Data

All previous data definitions were of fixed size, however, to represent data of an arbitrary size lists/cons need to be used.

List Mechanisms

(require 2htdp/image)

empty ; a list with "0" elements (null)

(cons "Flames" empty) ; a list with 1 string element

(cons "Leafs" (cons "Flames" empty)) ; a list with 2 string elements

(cons 10 (cons 9 (cons 8 empty))) ; a list with 3 numerical elements

(cons (string-append "C" "annucks") empty) ; a list with 1 element (evaluated)

(cons (square 10 "solid" "blue") ; a list of 2 image elements

(cons (triangle 20 "solid" "green")

empty))

(define L1 (cons "Flames" empty))

(define L2 (cons "Leafs" (cons "Flames" empty))

(define L3 (cons 10 (cons 9 (cons 8 empty)))

(first L1) ; returns "Flames"

(first L2) ; returns "Leafs"

(second L1) ; returns empty

(second L2) ; returns "Flames" (third Ln), (fourth Ln) ... (nth Ln)

(first (rest L1)) ; returns "Flames" <--- Prefered in CPSC 110 to (second Ln)

(first (rest (rest L3))) ; returns 8

(empty? empty) ; returns true

(empty? L1) ; returns false

(empty? (first (rest L1))) ; returns true

List Data Definition

;; ListOfElement is one of:

;; - empty

;; - (cons Element ListOfElement)

;; interp. a list of elements

(define LOE1 empty) ;example 1

(define LOE2 (cons 1 empty)) ;example 2

(define LOE3 (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 empty)))) ;example 3

(define (fn-for-loe loe)

(cond [(empty? loe) (...)]

[else

(... (first los)

(fn-for-loe (rest los)))]))

(@dd-template-rules one-of

atomic distinct

compound

self-ref)

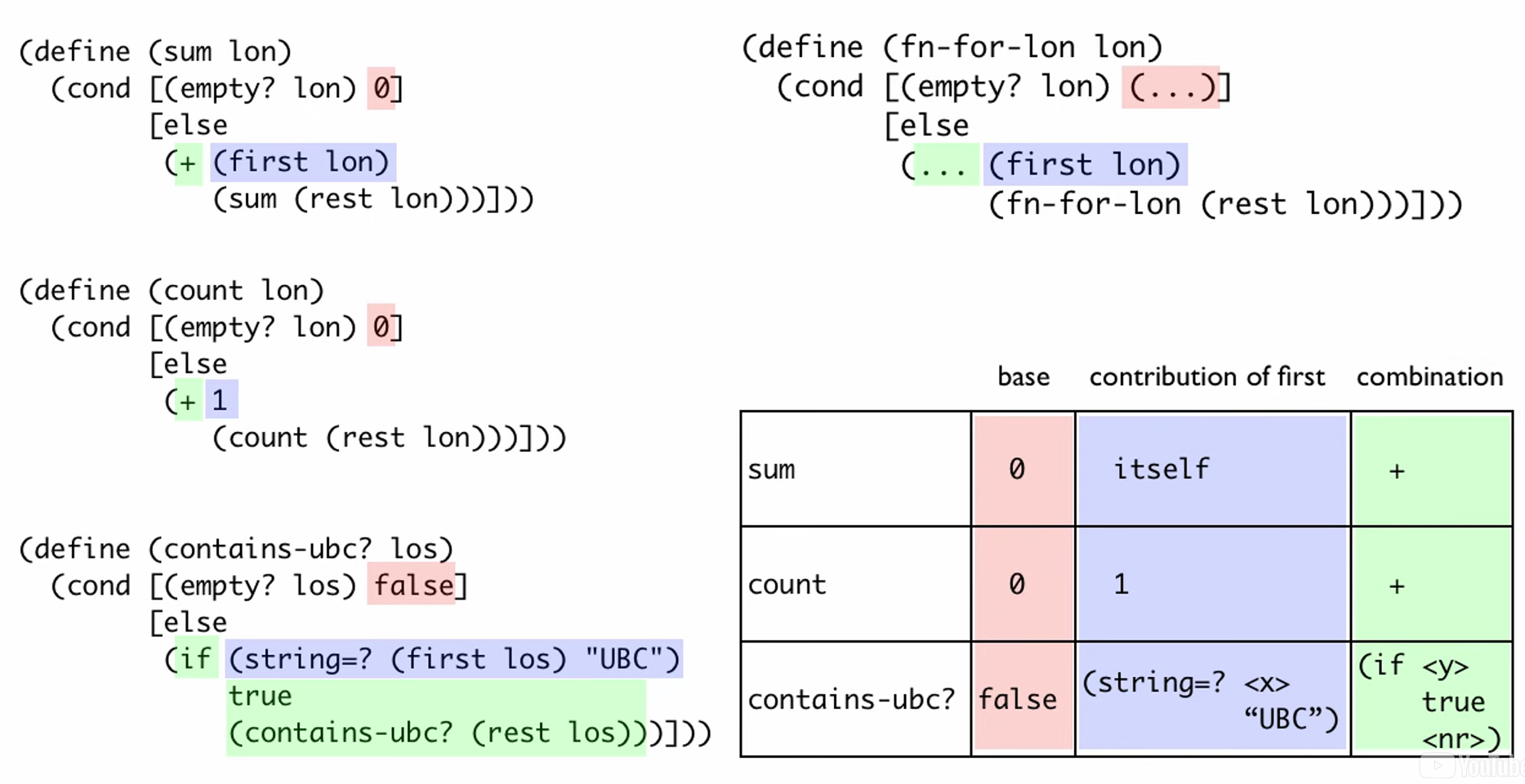

As long as the base case (n=0, list is empty) and n-1 case is accounted for the function will undergo a Natural recursion and not break. This requires either self referential data definitions or mutually referential data definitions. For the check expects, have one base case test, and at least one inductive case.

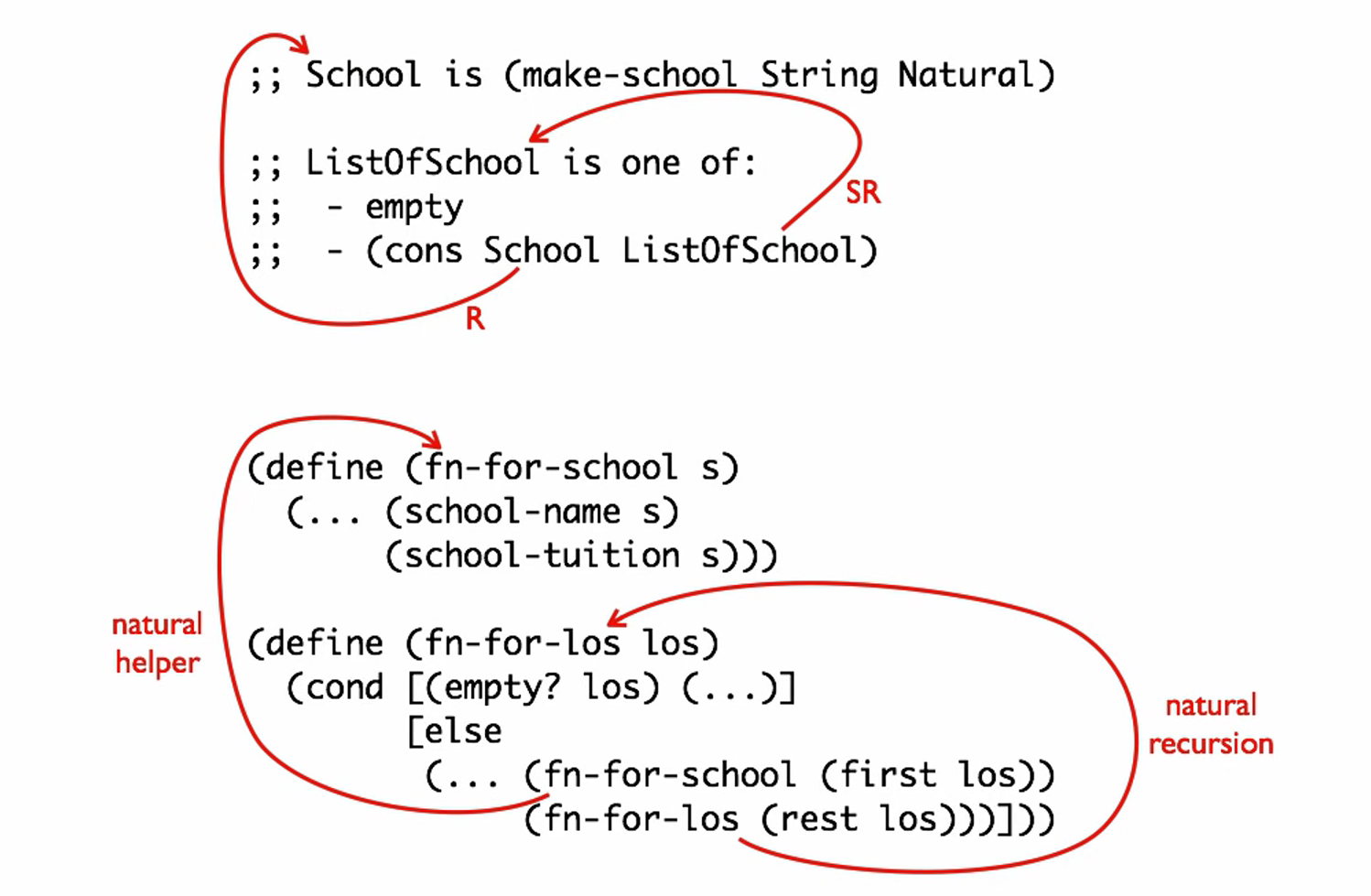

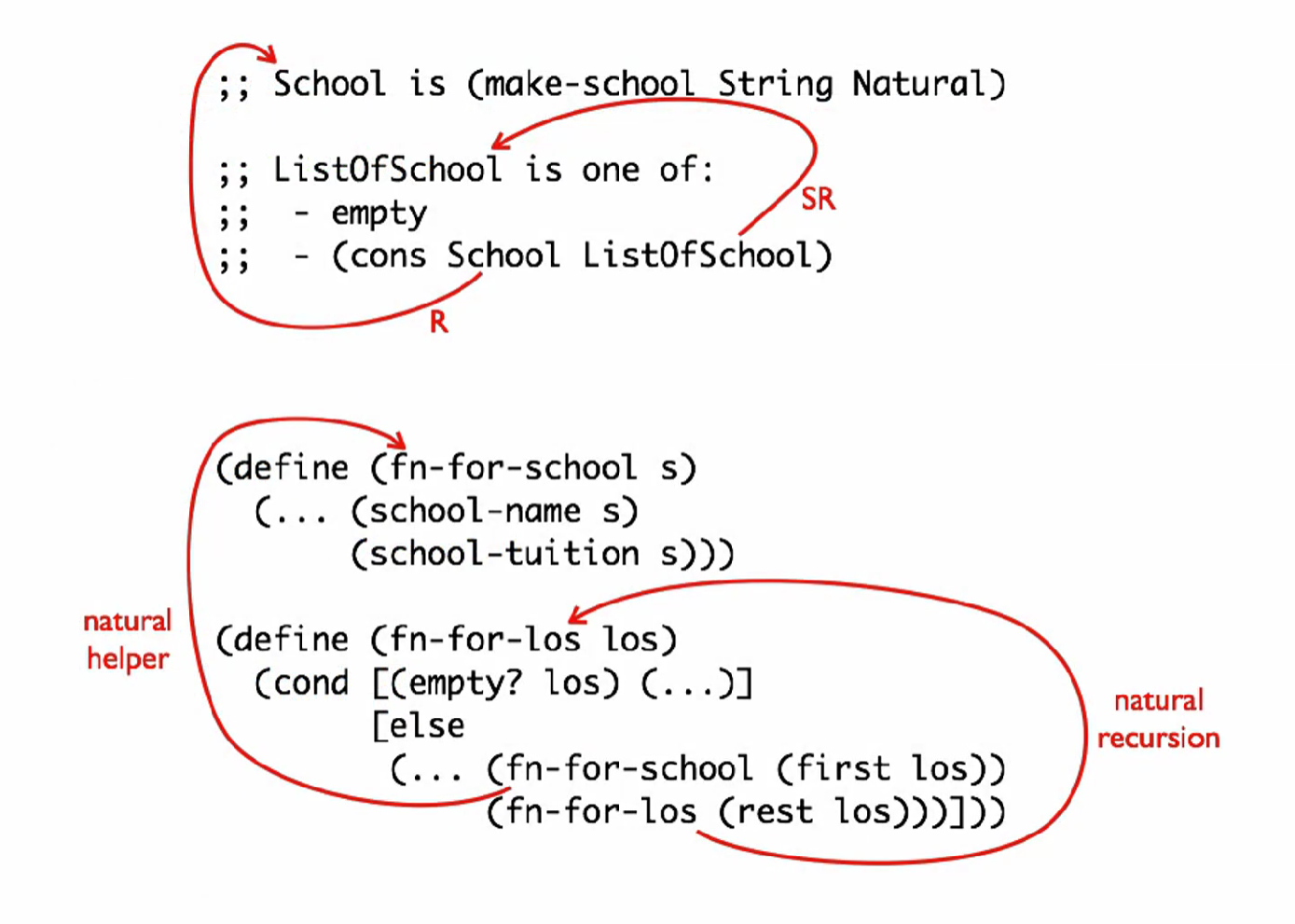

Reference

Reference refers to data definitions that relate to each other. For instance in a list of schools, there must be a reference to the school data type in list of schools. There will be a reference relationship in the type comment of list of school, a natural helper in the templates (for helper functions), and a helper function call.

MAKE CHECK-EXPECTS BEFORE FUNCTION DEFINITIONS

Helper functions are needed if there is

- a complicated conditional statement that operates on every element of a list

- a complicated operation needs to be made on every element

Keep all recursive calls it in the form:

(define (fn-for-loe loe)

(cond [(empty? loe) (...)]

[(<helper>) (<helper>)]))

This is designed so the natural recursion executes one function on all the elements of a list

Naturals

There are arbitrarily many natural numbers, so we can use a well-formed self-referential data definition to describe the type Natural. Doing so makes it easy to design functions that count down from a given natural number to 0. (Fancy way of saying for loop). Some useful functions for naturals include:

;; (add1 x), (sub x), (zero? x)

(add1 0) ; returns 1 similar to cons as it produces a list one longer

(sub1 1) ; returns 0 similar to rest as it produces a list one shorter

(zero? 0); returns true The data definition for a natural is as follows:

;; Natural is one of:

;; - 0 ; base case

;; - (add 1 Natural) ; self referential + recursive

;; interp. a natural number

(define N0 0) ; 0

(define N1 (add1 N0)) ; 1

(define N2 (add1 N1)) ; 2

(deine (fn-for-natural n)

(cond [(zero? n) (...)]

[else ... n (fn-for-natural (sub1 n))])) ; n is not in template but is very useful

An example of a function that uses a natural data definition is:

(@htdf sum)

(@signature Natural -> Natural)

;; Produce sum of Natural [0, n]

(check-expect (sum 0) 0) ; base case

(check-expect (sum 1) 1) ; 1 recurion

(check-expect (sum 3) (+ 3 2 1 0)) ; at least 2 recursions

(@template-origin Natural)

(template

(define (fn-for-natural n)

(cond [(zero? n) (...)]

[else ... (fn-for-natural (sub1 n)]))

)

(define (sum n)

(cond [(zero? n) 0]

[else (+ n (sub1 n)]))

Helpers

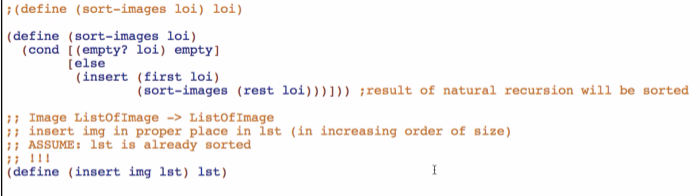

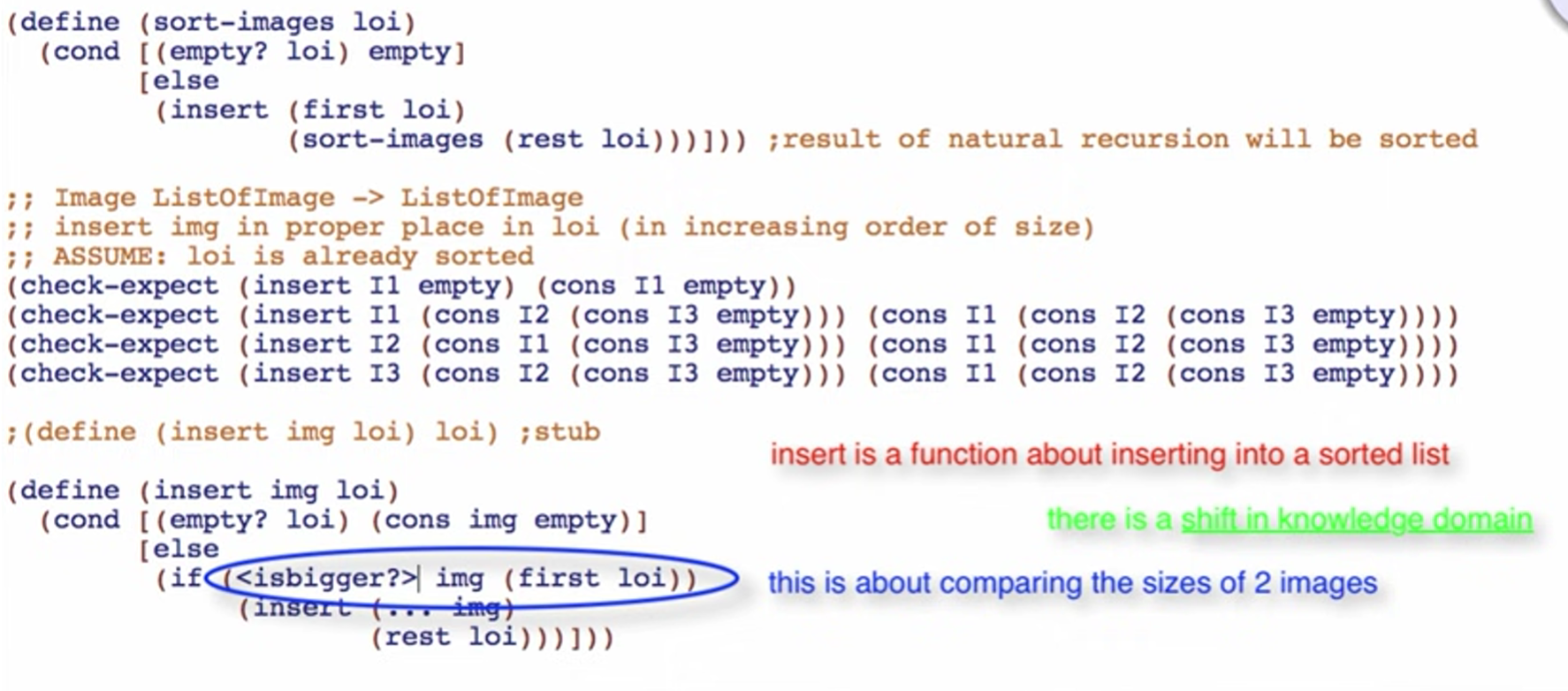

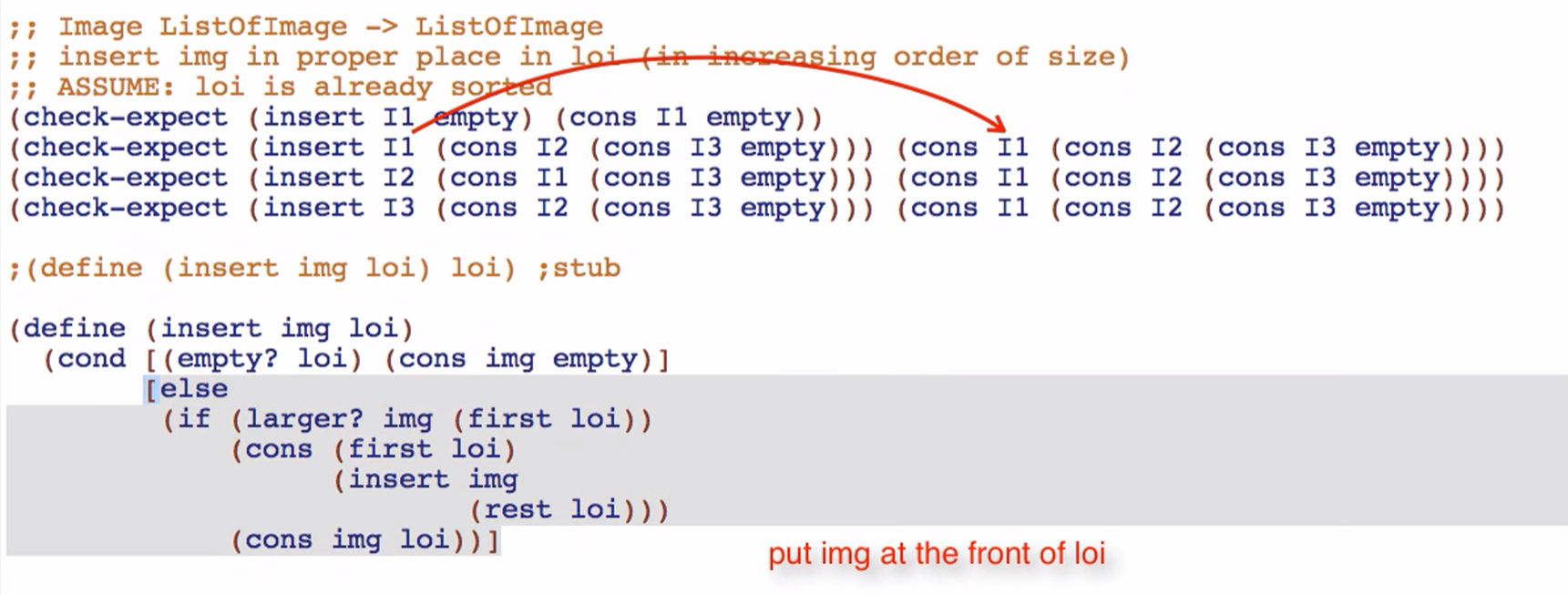

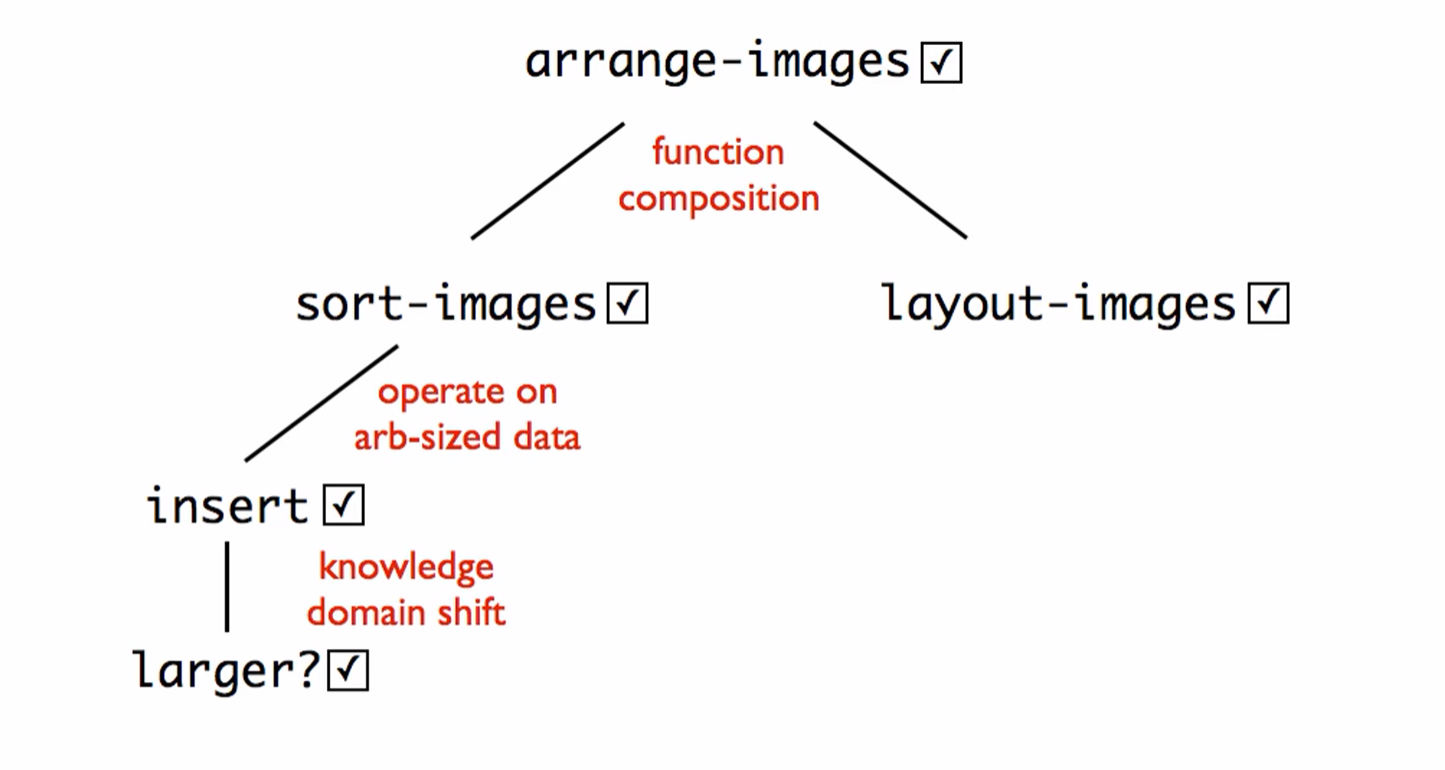

The key to solving large design problems is to break them down into smaller pieces. The recipes already do this, sometimes functions and data types need to be further decomposed into multiple types and functions.

Function composition is used when a function must perform two or more distinct and complete operations on the consumed data. For example: A function that must sort a list of images. First the images must be arranged by height, then displayed. In these cases, data definition templates for functions are not used instead,

(define (composition loe)

(operation2 (operation1 loe))

For example:

(define (arrange-images loi)

(layout-images (sort-images loi)))

- Note that the check expects for the function compositions do not need to test operations 1, 2 … but that the composition works. For instance, arrange images does not need to fully exercise layout-images, and sort-images; but they do need to exercise the combination of the two functions.

- Instead of having a stub for operations that returns empty, have it return loe as it is known that a list of elements are being passed. This will help with finding errors.

If operating on a list, a helper function MUST be used.

Sorting typically requires two recursive functions. One to insert an element to the right position, and another to sort the rest of the list.

A helper is also needed if the domain (purpose) of a function shifts. For instance,

^^ insertion example

^^ insertion example

Binary Search Trees (BST)

List Abbreviations

Before trying any abbreviation, go edit Beginning Student (Custom) to Beginning Student (with Abbreviations) This allows for the definition of lists, where the following are equivalent

(cons "a" (cons "b" (cons "c" empty))) = (list "a" "b" "c")

So when (cons "a" (cons "b" (cons "c" empty))) is evaluated, it returns the abbreviated form (list "a" "b" "c").

However, there are some small things to note when using lists:

(define L1 (list "b" "c")

(define L2 (list "d" "e" "f"))

(cons "a" L1) ; returns (list "a" "b" "c")

(list "a" L1) ; returns (list "a" (list "b" "c"))

Unless the goal is to make nested lists, cons should be used to add elements, and list should be used to define a list in its entirety. When operating on a list, append is used to “add” lists to each other.

(append L1 L2) ; returns (list "b" "c" "d" "e" "f")

append takes at least two lists/cons values. So if one element is being added it must be added as a list:

(append (cons "a" empty) L1) ; returns (list "a" "b" "c")

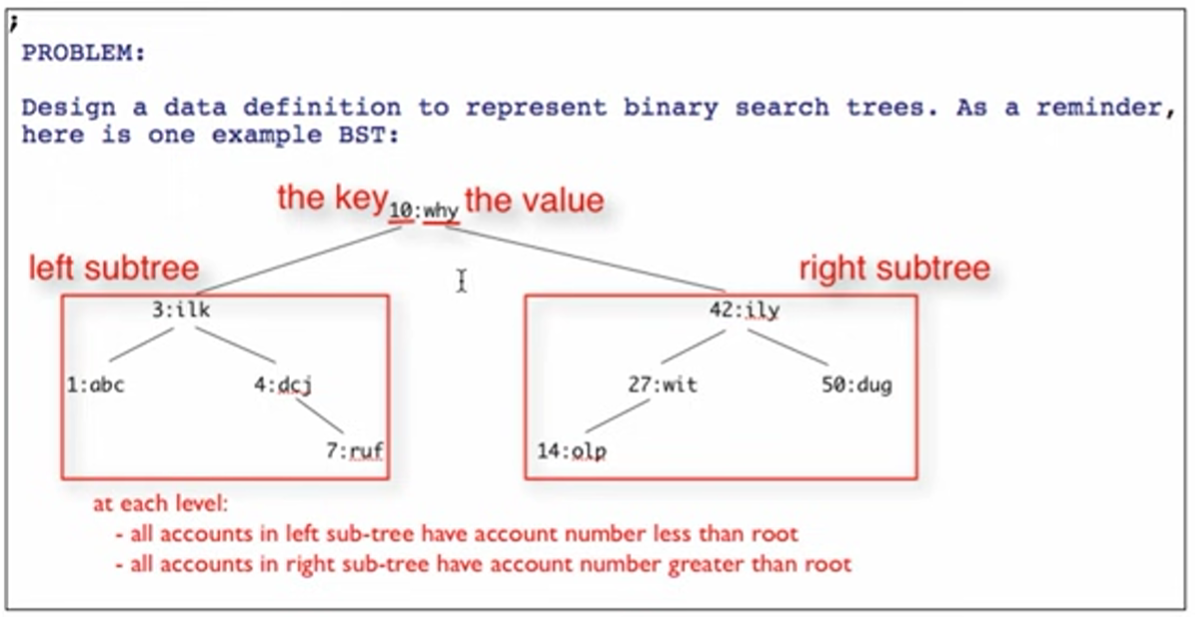

Binary Search Tree

The invariant for a binary search tree is that the child (branching value) to the left is left than the current node (circle) and the child to the right is greater than the current node. Generally there should be a relatively even number of nodes on both sides of the root (the highest value) and similar generations (levels of nodes)

The time complexity of finding an element in such a tree would be .

The time complexity of finding an element in such a tree would be .

Data Definitions for BSTs

Because the nodes on the left and right can be arbitrarily long, two self referential rules are needed.

(define-struct node (key val l r))

;; BST (Binary Search Tree) is one of:

;; - false

;; - (make-node Integer String BST BST)

;; interp. false means no BST, or empty BST,

;; key is the node key

;; val is the node value

;; l and r are left and right subtrees

;; INVARIANT: for a given node:

;; key is > all keys in its l(eft) child

;; key is < all keys in its r(ight) child

;; the same key never appears twice in the tree

(define BST0 false)

(define BST1 (make-node 1 "left" false false))

(define BST2 (make-node 4 "right" false (make-node 7 "hij" false false)))

(define BST3 (make-node 3 "top" BST1 BST2))

(define (fn-for-bst t)

(cond [(false? f)(...)]

[else (... (node-key t) ; Integer

(node-val t) ; String

(fn-for-bst (node-l t)) ; BST (self-ref)

(fn-for-bst (node-r t))])) ; BST (self-ref)

(@dd-template-rules one-of

atomic-distinct

compound

self-ref

self-ref)

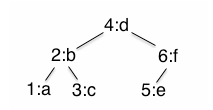

To represent binary search trees such as

Use:

(make-node 4 "d"

(make-node 2 "b"

(make-node 1 "a" false false)

(make-node 3 "c" false false))

(make-node 6 "f"

(make-node 5 "e" false false)

false))

Lookup in BSTs

(@template

(define (lookup-key t k)

(cond [(false? t) (... k)]

[else ... k

(node-key t)

(node-val t)

(lookup-key (node-l t) (... k))

(lookup-key (node-r t) (... k))]))

(define (lookup-key t k)

(cond [(false? t) false]

[else (cond [(= k (node-key t)) (node-val t)]

[(< k (node-key t)) (lookup-key (node-l t) k)]

[(> k (node-key t)) (lookup-key (node-r t) k)]

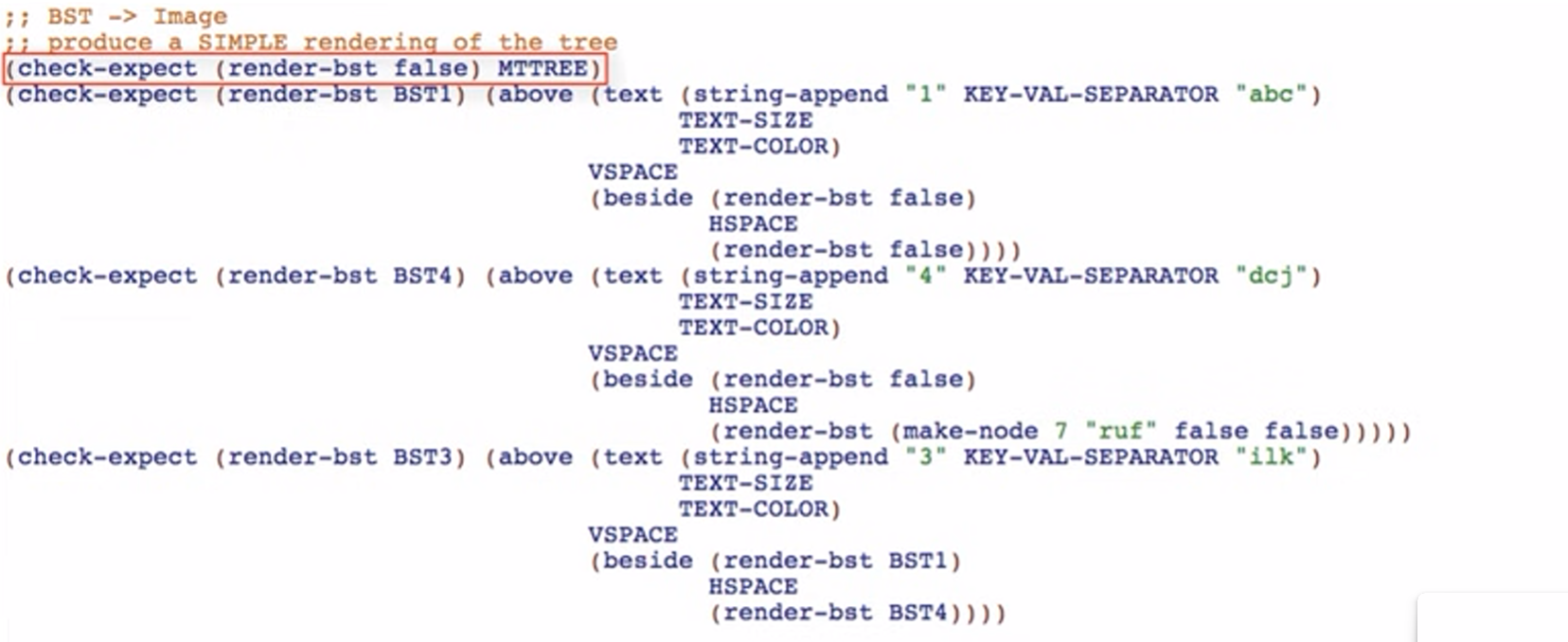

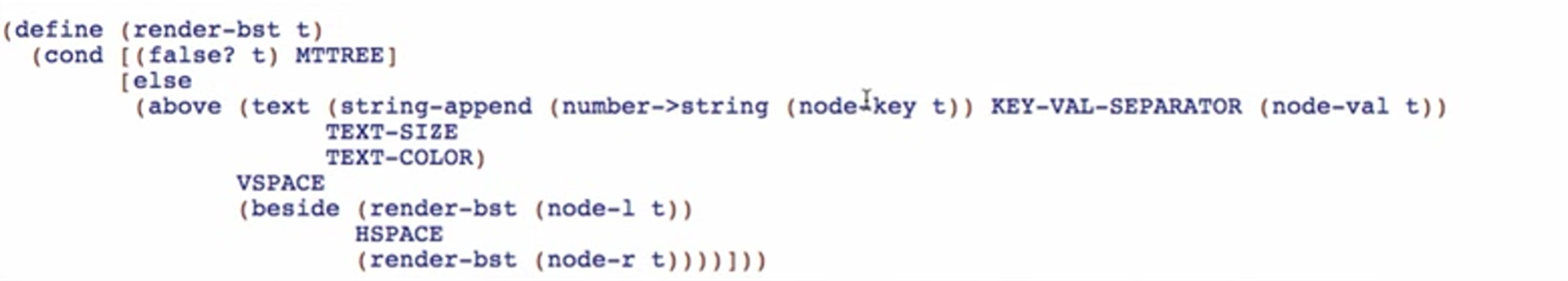

Rendering BSTs

Mutual Reference

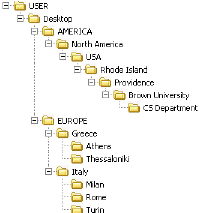

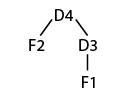

Mutually self-referential types can represent a tree of arbitrary depth and width. Similar to folders on a desktop:

Mutually Recursive Data

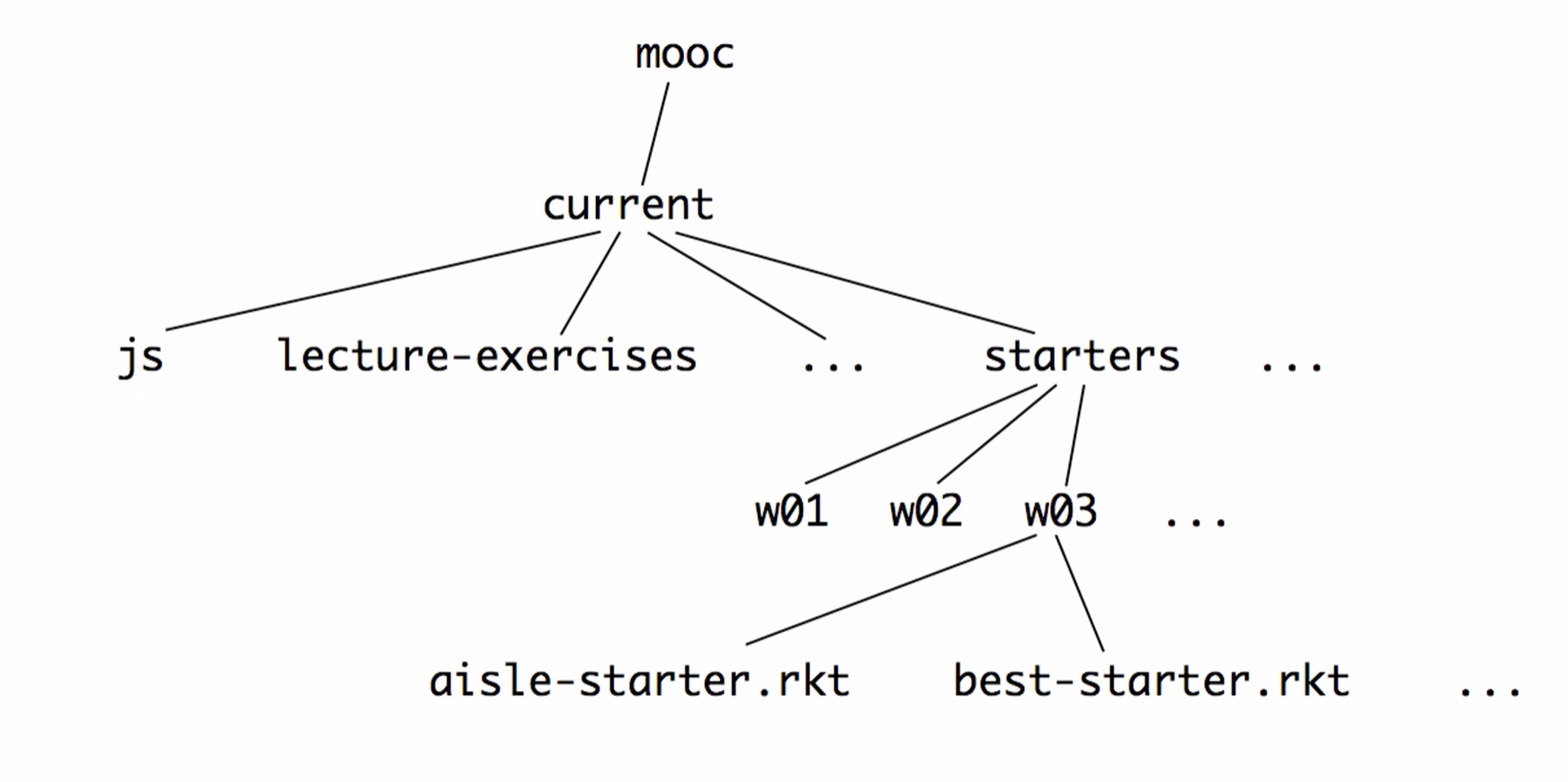

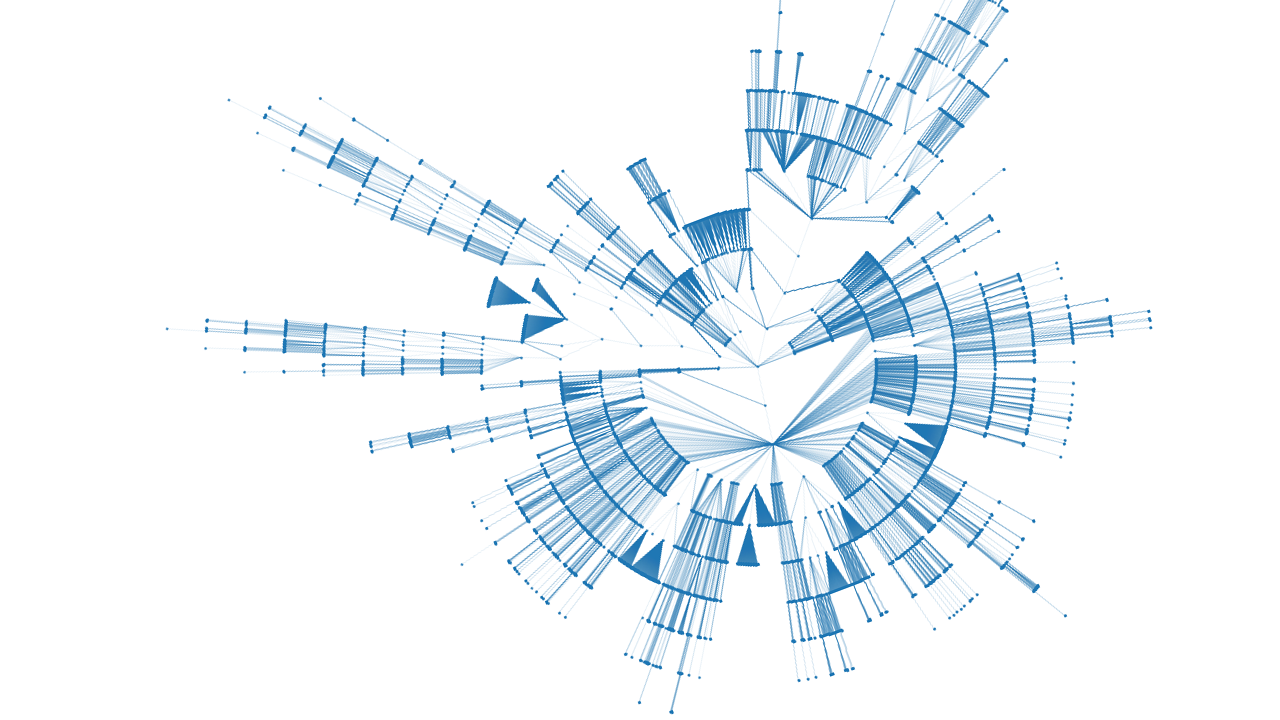

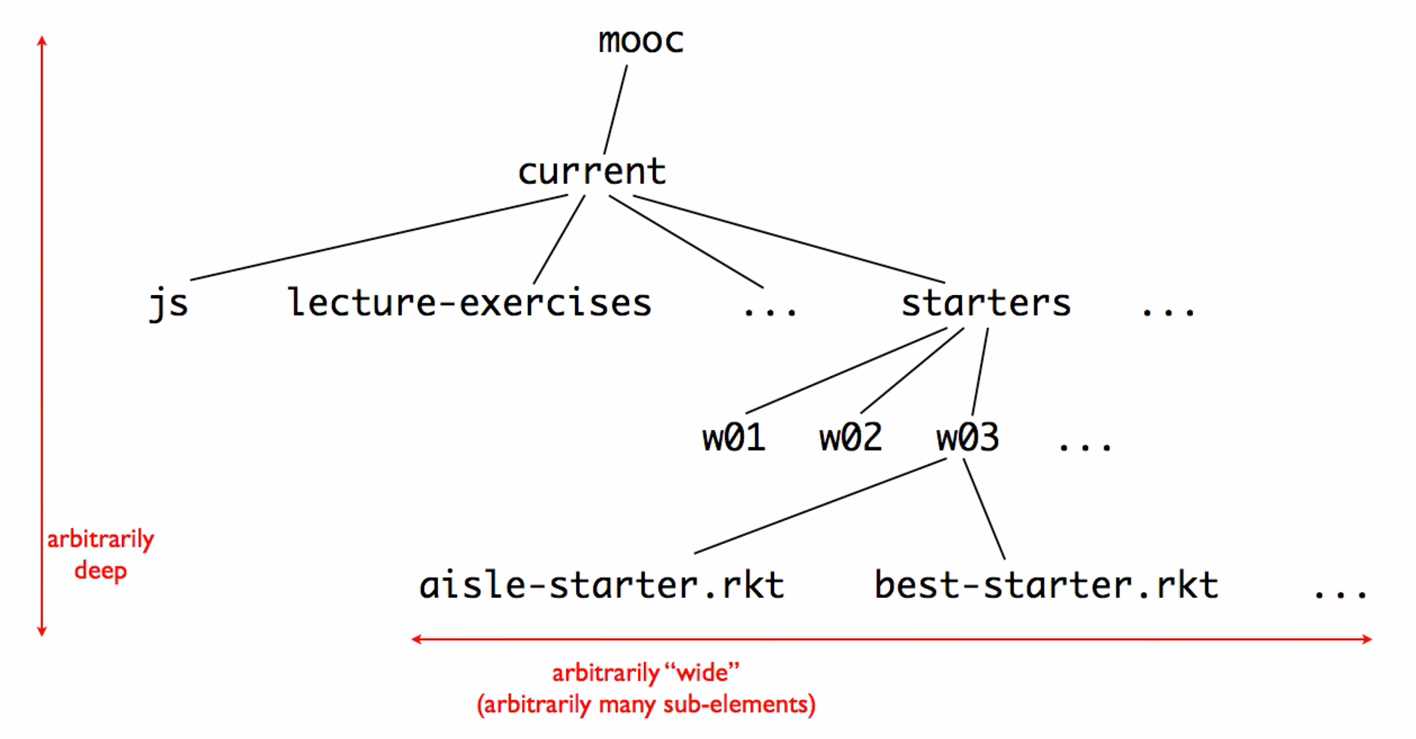

Unlike lists, which are only arbitrarily long in one dimension, arbitrary arity trees are arbitrarily long in two dimensions. It can be arbitrarily wide and deep:

Diagrams to Help Describe Arbitrary Arity Tree

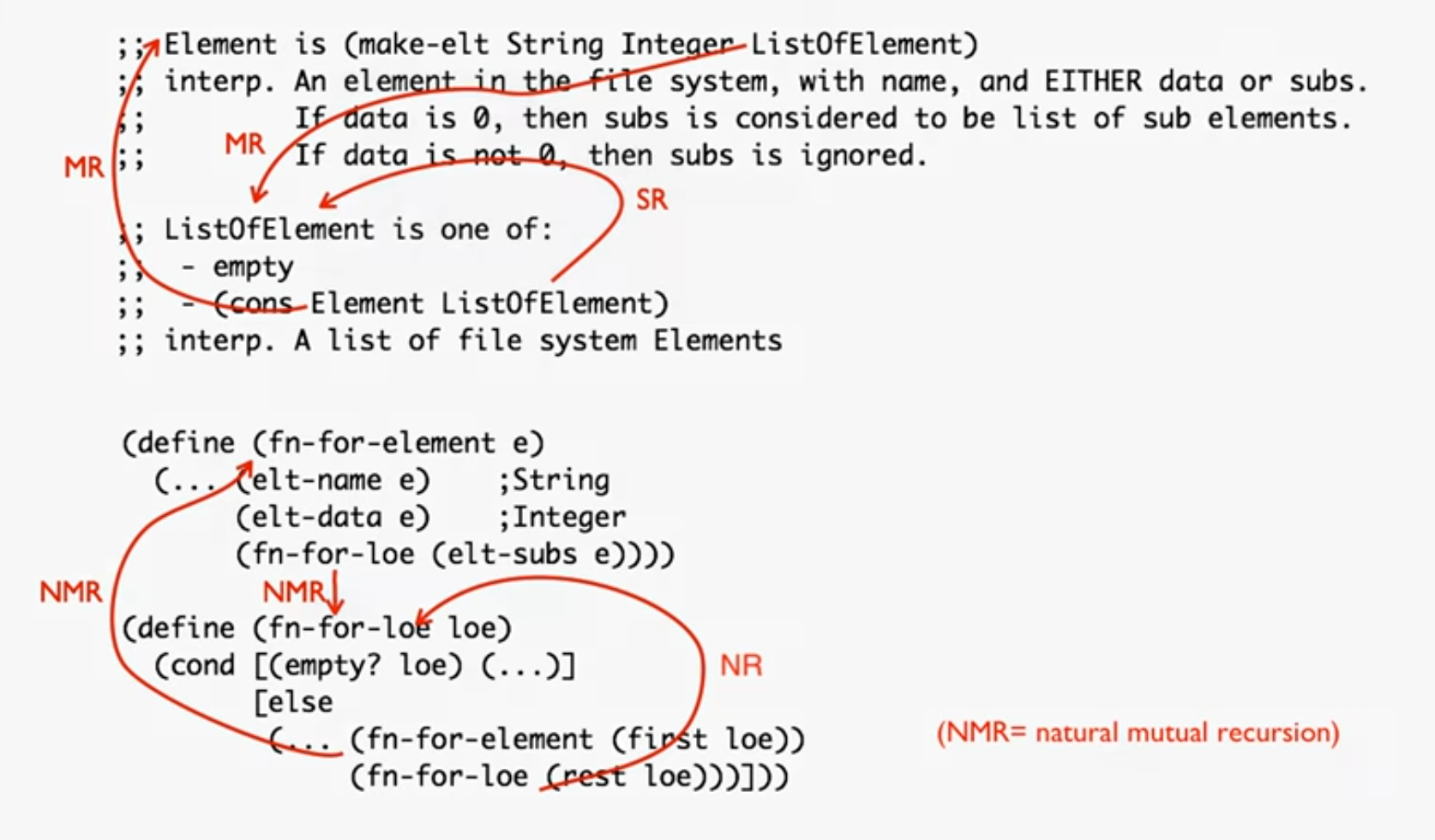

Templating Mutual Recursion

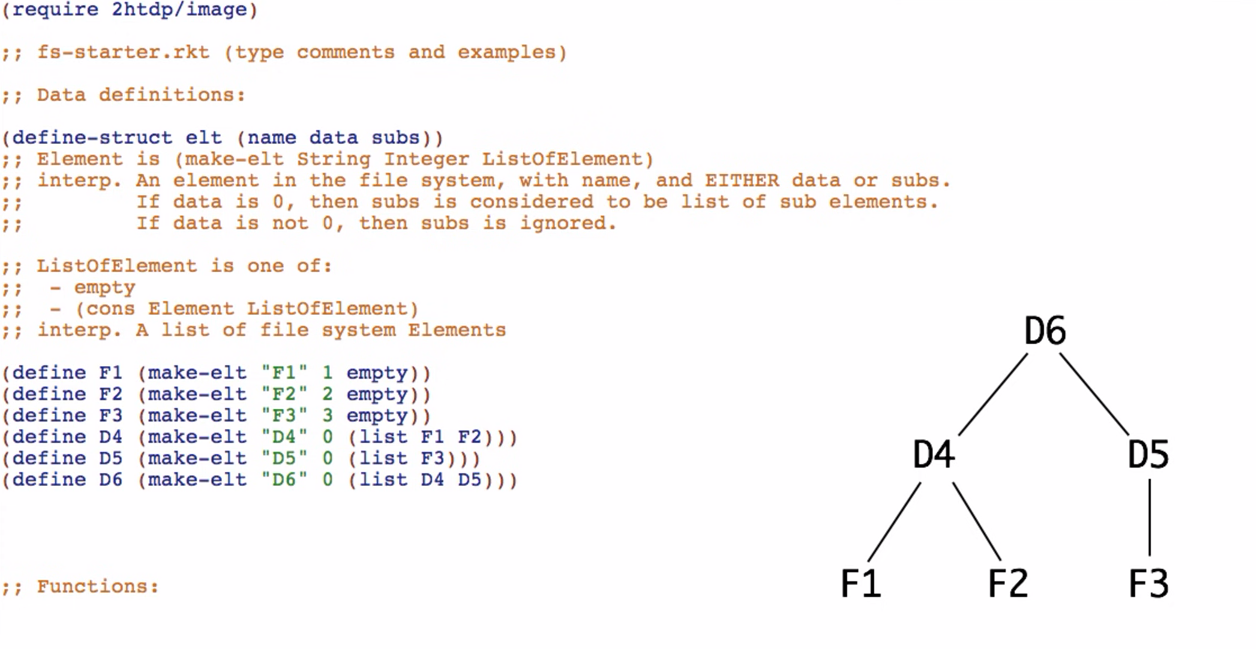

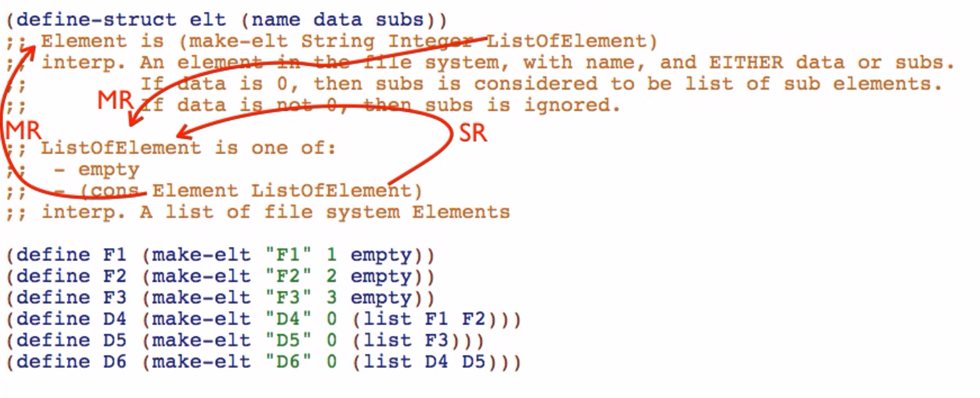

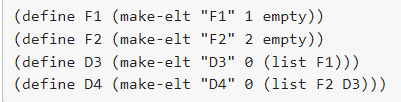

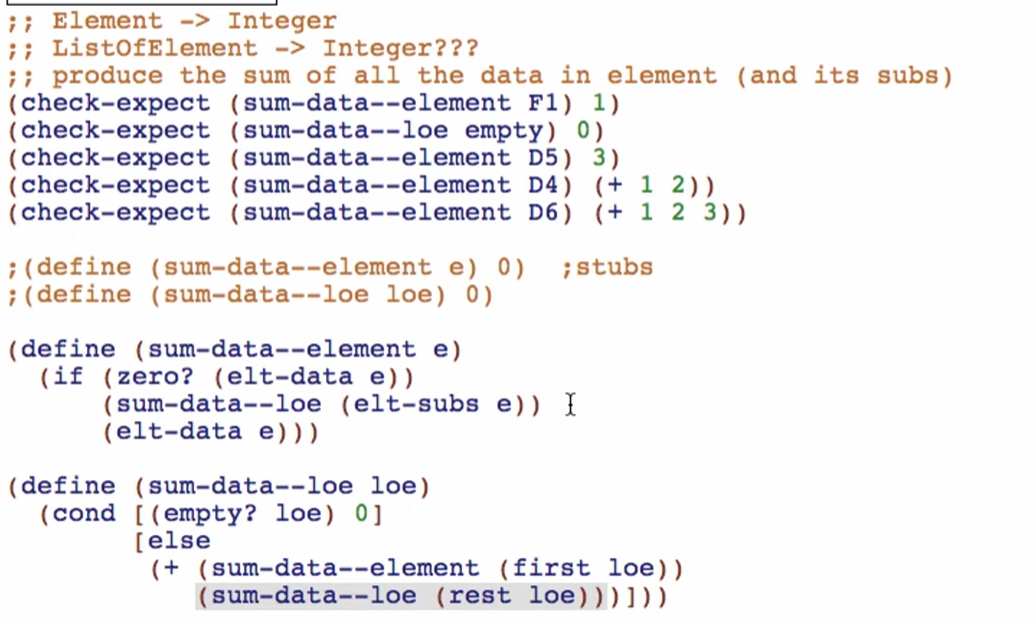

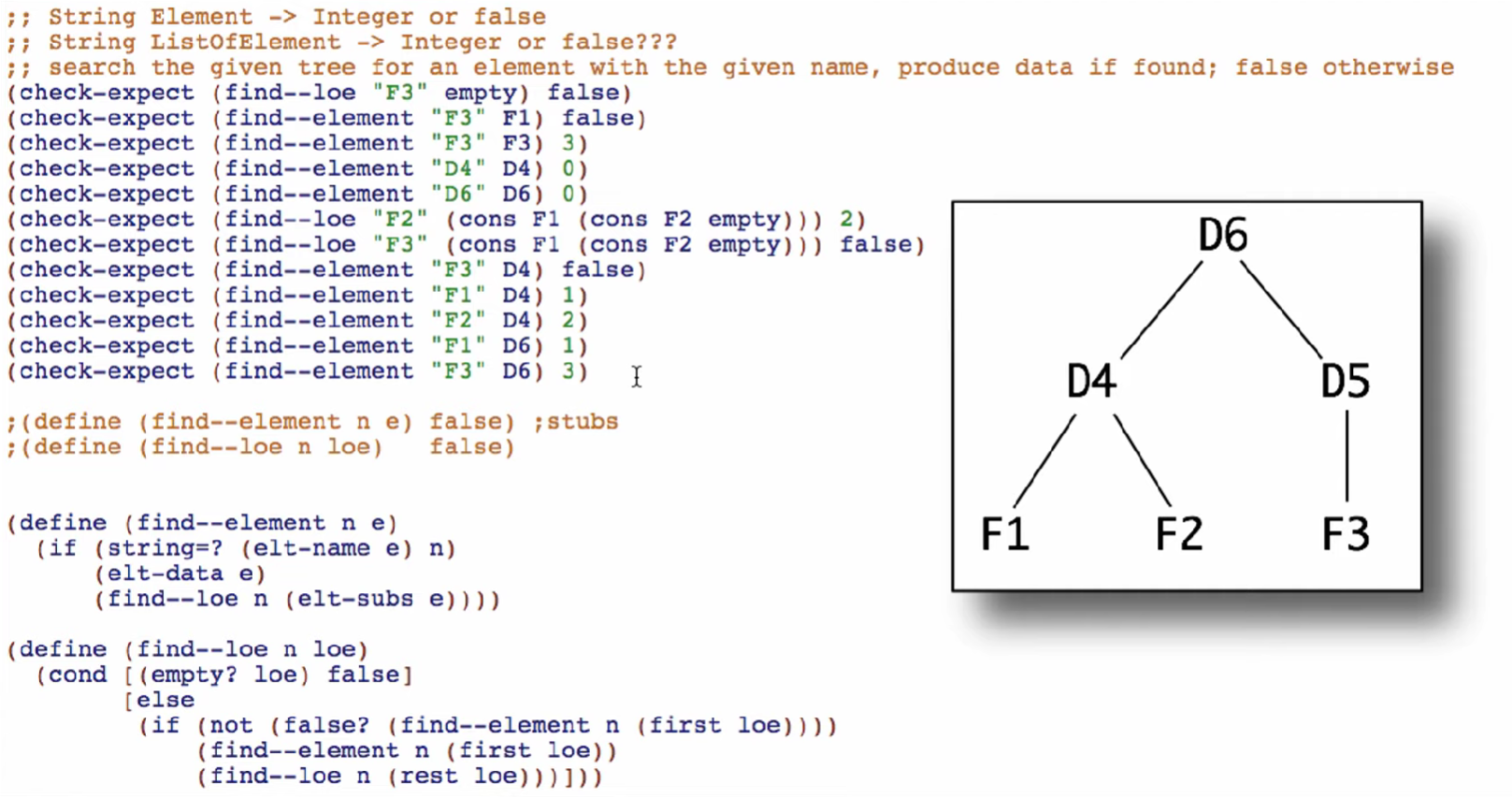

(define-struct elt (name data subs))

;; Element is (make-elt String Integer ListOfElement)

;; interp. An element in the file system, with name, and EITHER data or subs (more folders)

;; If data is 0, then subs is considered to be a list of sub elements

;; If data is not 0, then subs is ignored and elt is considered a piece of data (like a file)

;; ListOfElement is one of:

;; - empty

;; - (cons Element ListOfElements)

;; interp. A list of file system Elements

(define F1 (make-elt "F1" 1 empty))

(define F2 (make-elt "F2" 2 empty))

(define F3 (make-elt "F3" 3 empty))

(define D4 (make-elt "D4" 0 (list F1 F2)))

(define D5 (make-elt "D5" 0 (list F3)))

(define D6 (make-elt "D6" 0 (list D4 D5)))

;; Template rules used is no longer required

(define (fn-for-element e)

(... (elt-name e) ; String

(elt-type e) ; Integer

(fn-for-loe (elt-subs e)))) ;mutual-ref => ListOfElement

(define (fn-for-loe loe)

(cond [(empty? loe)(...)]

[(... (fn-for-element (first loe)) ;mutual-ref => Element

(fn-for-loe (rest loe))])) ;self-ref => ListOfElement

Functions on Mutual recursive Data

Functions are made in tandem: one for the elements, and another for the list of elements. Group examples, definitions, signatures (everything) together when writing mutually referential data types.

MUTUALLY REFERENTIAL NATURAL RECURSION MUST BE “TRUSTED”

Backtracking Search

Two One-Of Types

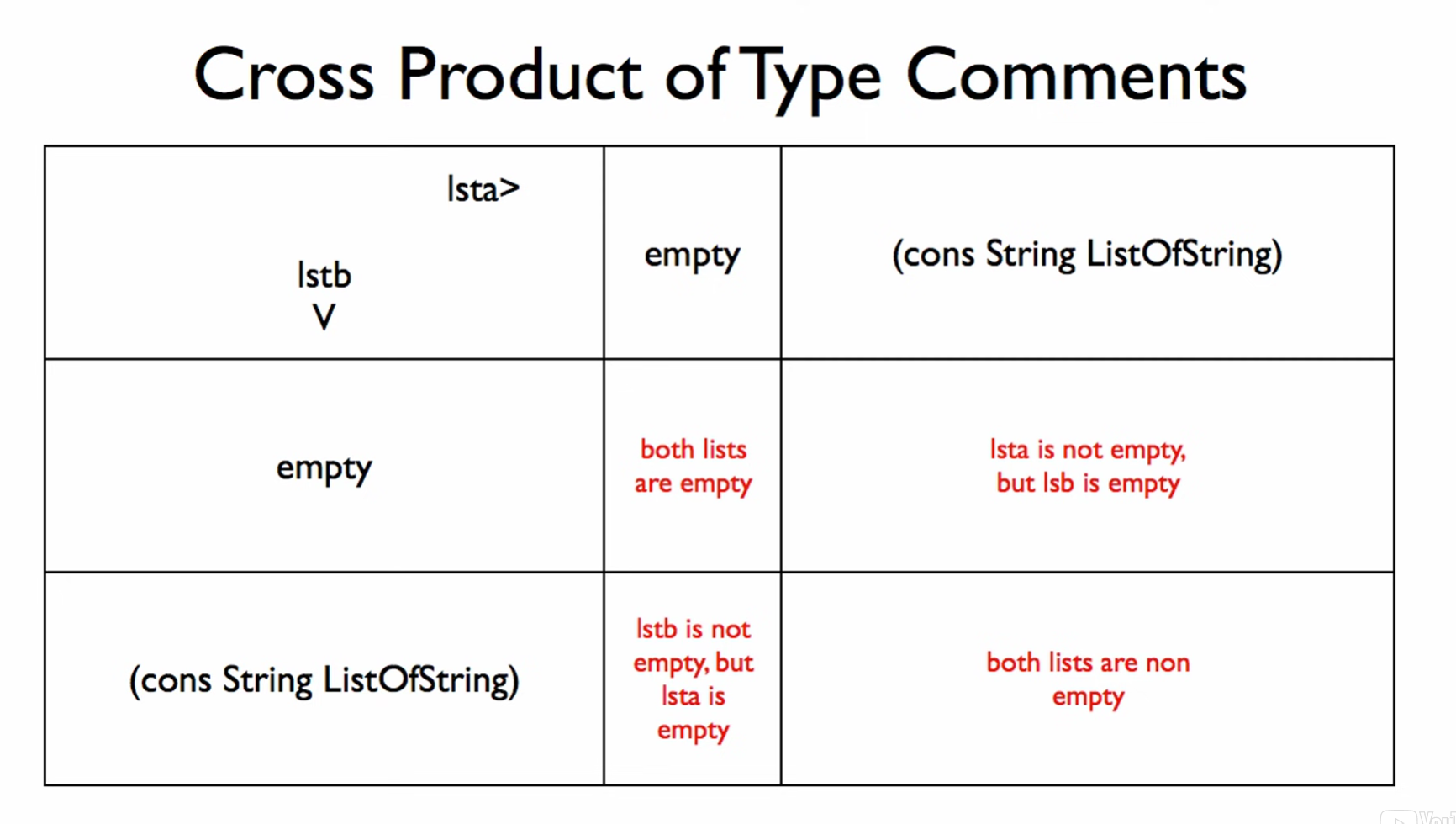

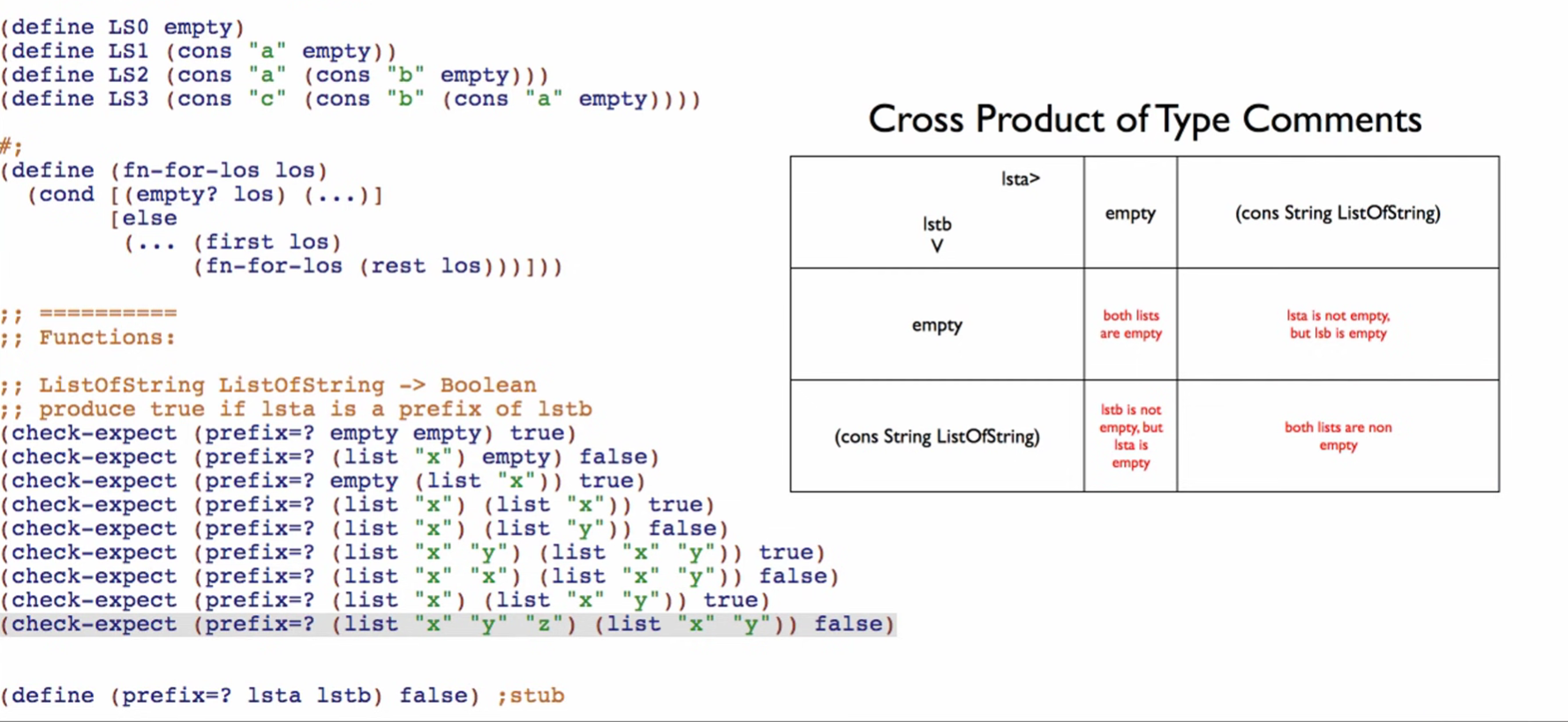

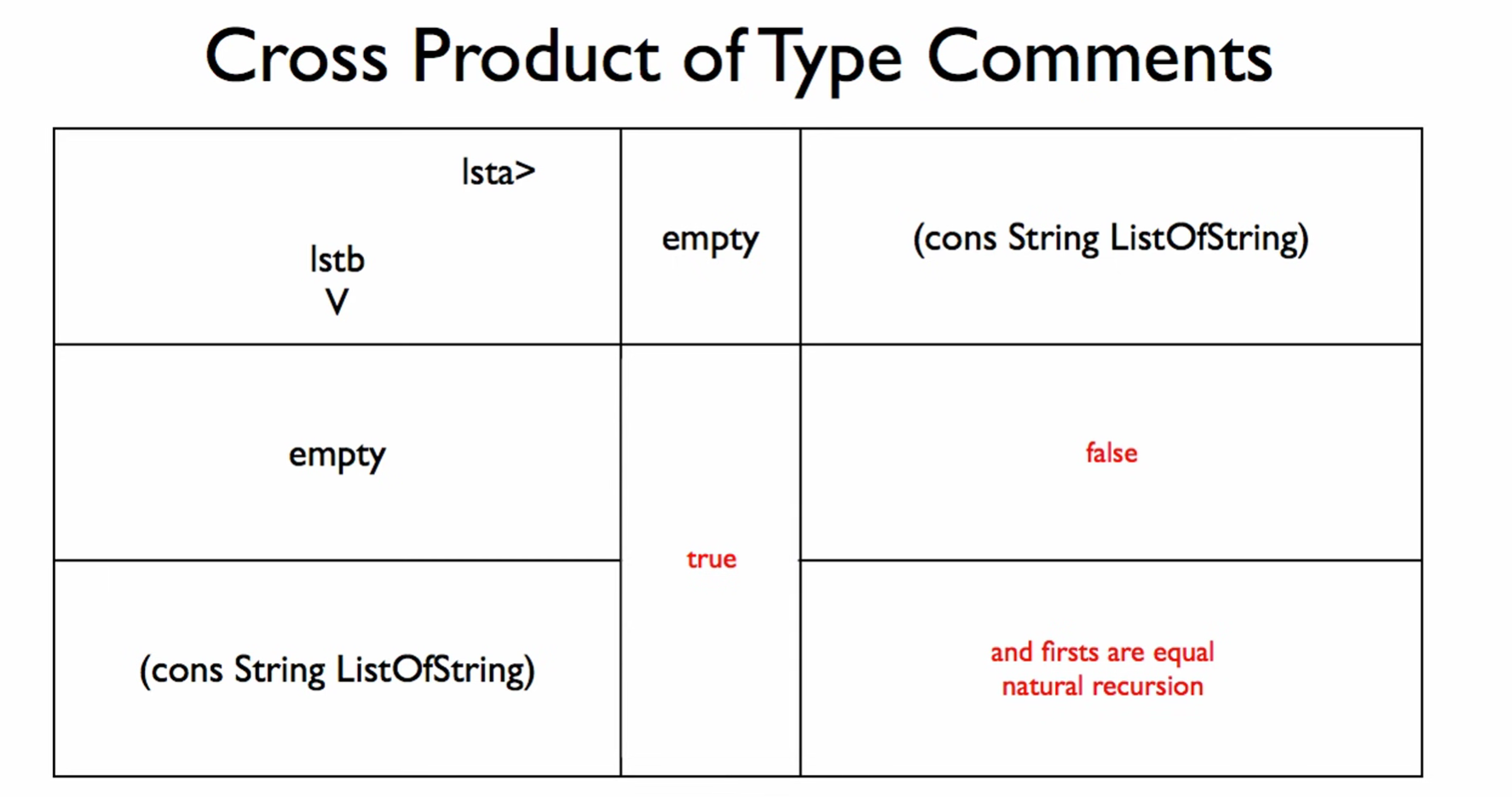

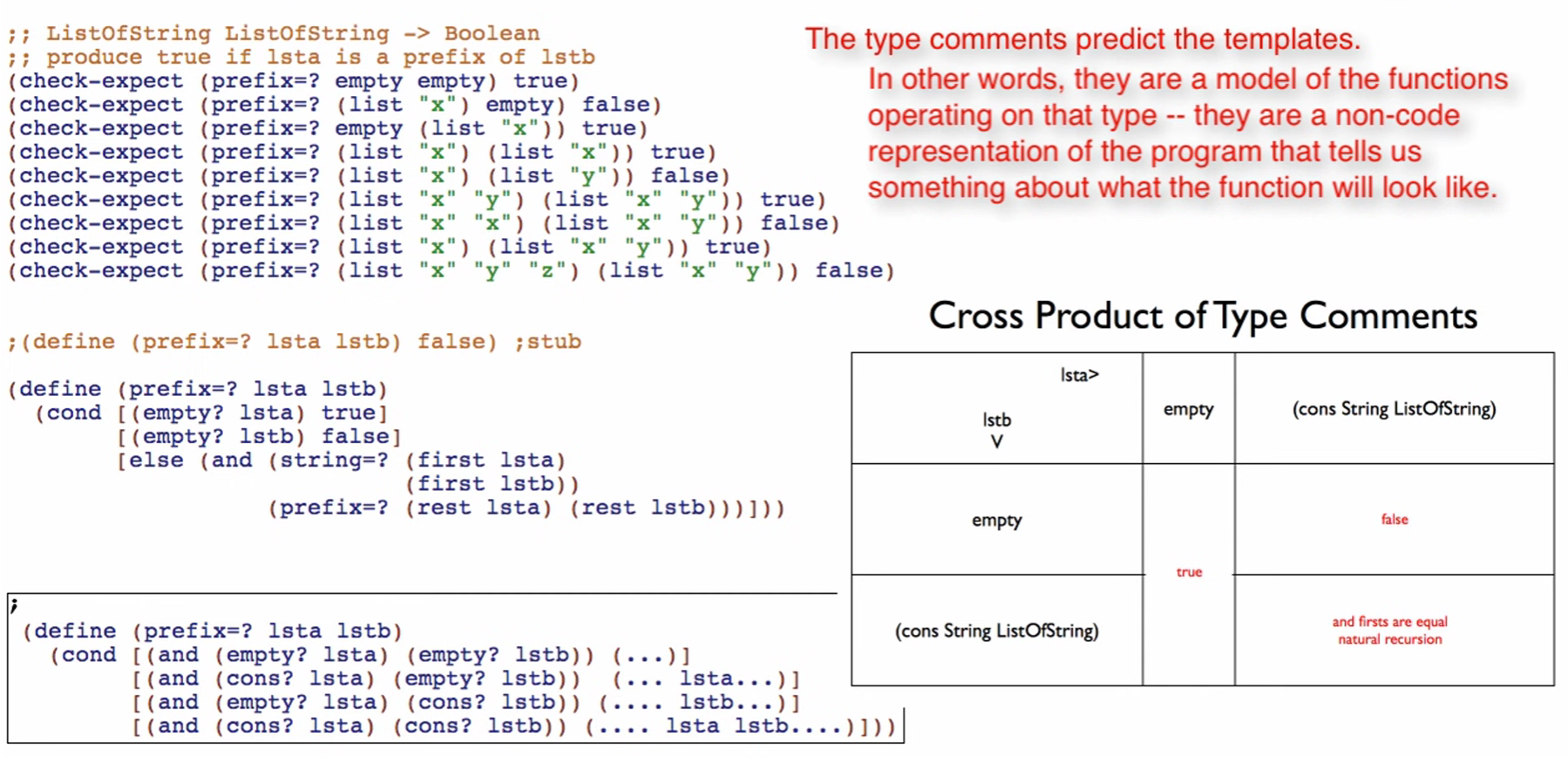

Cross Product Type Comments

When taking in two “one-of” types such as a list, the cross product of the type comments can be used to deduce the behavior of a function. This works for all types of data as long as it follows the one-of type definition: a “ListOfString” can be consumed with “ListOfElement” for instance.

If there are more than two cases within a one-of type comment then the cross product expands to accommodate for EVERY case. For instance list a is one of empty, (cons String ListOfString), and false would imply 3 columns (or rows) to cross with the other one-of type comment. For the cross product of two “one-of” implies the need for at least 4 cases.

Cross Product Code

Not all cases need to be investigated. When writing a cross product type comment, the cases can be simplified to reduce the number of cases. For instance:

And writing the conditionals for the template would look like this:

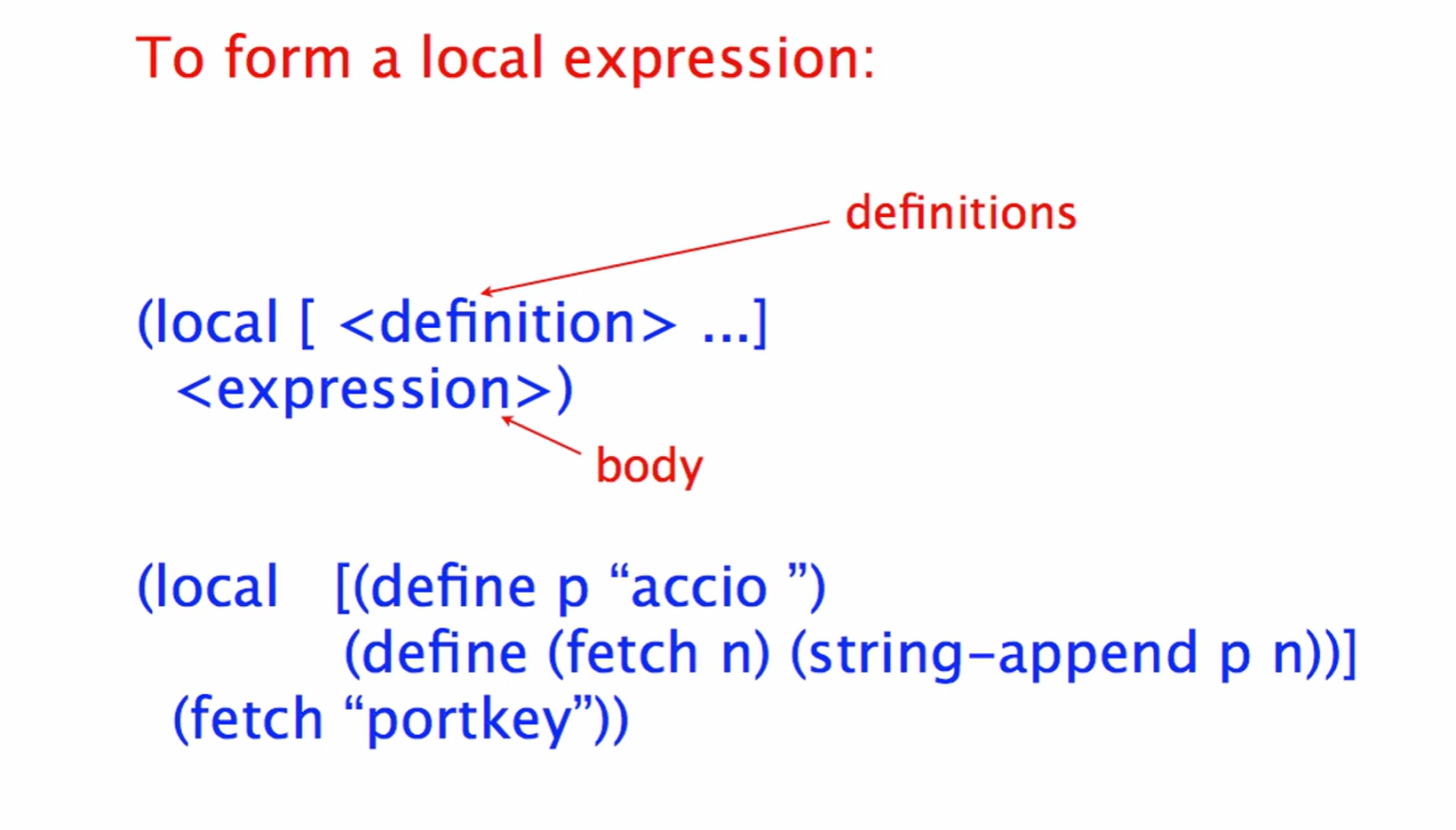

Local

When dealing with very large programs, or ones that are worked on by multiple people, using local expressions are used. In Dr. Racket, ISL is used to define variables, functions and expressions within a section of the code.

For the following:

(local [(define a 1) (define b 2)

(+ a b)])

(+ a b)

The expression within the local produces 3 as the variables are defined within the scope of that local. However, when trying to evaluate an expression where the variables are not defined, they cannot be evaluated as a and b are not defined outside the scope of the local expression.

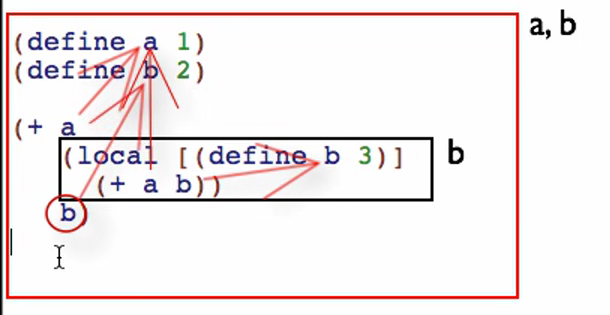

Lexical Scoping

Using “Check Syntax” in Dr. Racket allows you to see what is being referenced when a variable is called.

Evaluation Rules for local

(define b 1)

(+ b

(local [(define b 2)]

(* b b ))

b )

;; Evaluates to...

(+ 1

(local [(define b 2)] ;; recall that local is an expression

(* b b ))

b )

;; 3 things occur simultaneously when a local expression is evaluated

;; - Renaming: Renaming b to b_0

;; - Lifting: Defining b_0 with on a global scope

;; - Replace entire local with renamed body: remove 'local'

(define b_0 2)

(+ 1

(* b_0 b_0))

b )

...

Encapsulation

When writing mutually recursive functions such as finding the sum of all the elements in a list, instead of writing sum-data--element and sum-data-loe globally, the following can be done instead.

(define (sum-data e)

(local [(define (sum-data--element e) (...))

(define (sum-data--loe e) (...))]))

This leaves the function sum-data as the only global function. Because of this, the amount of check-expects are reduced as sum-data--loe cannot be operated on globally (previously the list functionality was checked by passing a list of elements instead of an element with children). In fact, the function only runs one function (typically the one that operates on an element) at after the definitions:

(define (sum-data e)

(local [(define (sum-data--element e) (...))

(define (sum-data--loe e) (...))]

(sum-data--element e))) ;; <-- Trampoline

A more complete example:

(define (all-names e)

(local [(define (all-names--element e)

(cons (elt-name e)

(all-names--loe (elt-subs e ))))

(define (all-names--loe e)

(cond [(empty? loe) empty)]

[else

(append (all-names--element (first loe))

(all-names--loe (rest loe)))]))]

(all-names--element e))) ;; <-- Trampoline

At this stage, stubs can be deleted. Just ensure that all code runs. Additionally, you can start with pre-encapsulated templates, but you don’t have to. Being able to test base examples of the inner functions is helpful. Encapsulation is especially helpful in hiding all of the unnecessary functions (take libraries for instance.)

Avoiding recomputation

To find the time complexity of a function, you can use the primitive, (time (foo ...)) to see the general trend of time taken as , number of operated data increase. To avoid cases of exponential computation that is significantly decreasing the run time of a program, encapsulating the “exponential step” decreases the time taken substantially.

(local [define (find-element n e)

(if (string=? (elt-name e) n)

(elt-data e)

(find--loe n (elt-subs e)))]))

(define (find--loe n loe)

(cond [(empty? loe) false]

[else

(local [(define try (find--element n (first loe)))]

(if (not (false? try))

try

(find--loe n (rest loe))))]))]

(find--element n e)))Abstraction

To reduce the amount of repetition in code, functions can be abstracted to allow operations as parameters with data. Take the two functions:

(define (square-roots lon)

(cond [(empty? lon) empty]

[else (cons (sqrt (first lon))

(square-roots (rest lon)))]))

(define (square lon)

(cond [(empty? lon) empty]

[else (cons (sqr (first lon))

(square-roots (rest lon)))]))

But if the function were to be redefined with the operand swapped out then,

(define (map2 foo lon)

(cond [(empty? lon) empty]

[else (cons (foo (first lon))

(square-roots (rest lon)))]))

(map2 sqr lon) ; this is equivalent to the previous definition for square

(map2 sqrt lon) ; this is equivalent to the previous defintiion for square root

Note that this technique is called map (in mathematics). However, in Dr. Racket, map is already taken as a primitive type. So it is common for map2 to be used instead. map2 is a higher order function that can consume one or more functions and can produce a function. This process is also known as parameterization.

Templating Abstract Functions

When templating abstract functions, the order is reversed from the typical order:

- Test and debug abstract function

- Code the function body

- Template and inventory

- Define examples, wrap each check-expect

- Signature, purpose and stub.

If asked to abstract a function, existing examples can be restructured for an abstract function. E.g.

(define (LOU1) (list McGill UoT UBC))

(check-expect (contains-ubc? LOU1) true)

(check-expect (constains? "UBC" LOU1) true)

A common purpose for operations on lists is:

;; given fn and (list n0 n1 ...) produce (list (fn no) (fn n1) ...)

A filter function:

;; given a list, produce a list of only the leements that satisfy the predicate p

When finding a signature for an abstract function look for the clearest case. Look at all the function can produce and put it into the signature. Look at predicates like (empty?) to see if its a list, (string=?) to see if strings are equal, (first loe), (rest loe) indicate a list etc. The signature for (contains?) would be:

;; (@signature String (listof String) -> Boolean)

There is no longer a need for defining ListOf___ data types. They can now be referred to as (listof ___)

For functions that operate on all types of data, type parameters can be used in place of a concrete type. The convention is to write it as a capital letter (X). E.g.

(define (map2 fn lon)

(cond [(empty? lon) empty]

[else

(cons (fn (first lon))

(map2 fn (rest lon)))]))

The list must be of X, and the operation that fn performs on X is the result Y. As the abstract function produces a list of ___ it must be a (listof Y)

;; (X->Y) (listof X) -> (listof Y)

Built in Abstract Functions

In Dr. Racket, there are built in abstract functions e.g. map and filter that can be used to create functions. foldr is the abstraction of sum and product. There are other useful abstract functions such as:

(foldr + 1 (list 1 2 3)) ; returns (list 2 3 4)

(foldr * 2 (list 1 2 3)) ; returns (list 2 3 6)

(build-list n foo) ; n is the number of elements (0, 1, 2 ... n-1); foo is a function on n

(build-list 3 identity) ; returns (list 0 1 2)

(build-list 4 sqr) ; returns (list 0 1 4 9)

Determine which abstract function to use by the signatures:

build-list=Natural -> (listof X)filter=(listofX) -> (listof X)map=(listof X) -> (listof Y)andmap=(listof X) -> Booleanormap=(listof X) -> Booleanfoldr=Y (listof X) -> Yfoldl=Y (listof X) -> Y

It is often useful to do an operation on all element to a certain number n. To do this, write a composition of functions. E.g.

(define (sum-to n)

(foldr + 0 (build-list n identitiy)))

Closures

When using abstraction there may be cases where the function does not yet exist. Here they can always be defined with local but there is a subcase where it must be defined with local.

(define (wide-only loi)

(local [(define (wide? i) (> (image-width) (image-length)))]

filter wide? loi))

When the body of a function that is passed to an abstract function refers to a parameter of the outer function, the function passed must be defined using local. It simply cannot be defined globally. A closure refers to a function that can only be defined within the function as its parameters do not globally:

(define (wider-than-only w loi)

(filter wider-than? loi))

(define (wider-than? i)

(> (image-width i) w))

w is defined within the abstract function but not globally so the function does not run.

Fold Functions

A fold function can be manually written as:

(@signature (X Y -> Y) Y (listof Y) -> Y)

(define (fold fn b lox)

(cond [(empty? lox) b]

[else

(fn (first lox)

(fold fn b (rest lox)))]))

A mutually recursive fold function can be written as:

(@signature (String Integer Y -> X) (X Y -> Y) Y Elmeent -> X)

(define (fold-element c1 c2 b e)

(local [(define fn-for-element e)

(c1 (elt-name)

(elt-data)

(fn-for-loe (elt-subs e))))

(define (fn-for-loe loe)

(cond [(empty? loe) b]

[else

c2 (fn-for-element (first loe)

(fn-for-loe (rest loe)))]))]

(fn-for-elemeent e)))

Generative Recursion

Generative recursion is in many ways similar to structural recursion: a function calls itself recursively (or several functions call themselves in mutual recursion). For the recursion to terminate, each recursive call must receive an argument that is in some way “closer to the base case”. That is what guarantees the recursion will eventually terminate. In the structural recursion we have already seen, the nature of the data definitions and the template rules provide us the guarantee that we will reach the base case. But in generative recursion we have to develop that proof for each function we write.

Termination Arguments

A well formed termination argument has the following:

- Base case: (AKA Trivial) Whenever the trivial condition is met, run the trivial answer e.g.

(<= s CUTOFF) - Reduction step: Some operation that reduces the input towards the base case e.g.

(\ s 2) - Argument that repeated application of reduction will eventually reach the base case: As long as the cutoff is > 0, and s starts >=0 repeated division by 2 will eventually be less than the cutoff.

(if (trivial? s)

(base case)

(fn ... (local [(define fn2) ...]

fn (reduction s)))

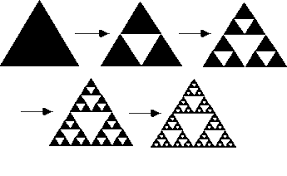

Generation of Fractals

The code for generating a fractal is as follows (Sierpinski triangle)

(define CUTOFF 2)

(@signature Number -> Image)

;; Produce a Sierpinski triangle of the given size.

(check-expect (stri CUTOFF) (triangle CUTOFF "outline" "red"))

(check-expect (stri (* 2 CUTOFF)) (overlay (triangle (* 2 CUTOFF) "outline" "red")

(local [(define sub (triangle CUTOFF "outline" "red")]

(above sub

(beside sub sub)))))

(define (stri s) (square 0 "solid" "white")) ; stub

(@template

(define (genrec-fn d)

(if (trivial? d) ;similar to base case

(trivial-answer d)

(... d

(denrec-fn (next-problem d)))))

(define stri s)

(if (<= s CUTOFF)

(triangle s "outline" "red")

(overlay (triangle s "outline" "red")

(local [(define sub (stri (/ s 2)))]

(above sub

(beside sub sub))))

Search

First switch to intermediate student (with lambda). Lambda functions are used when the function is small, and only used in one place. Lambda is typically used for abstract functions that use local to define functions that will only be used once (closures). For lambda functions, they are defined and not given a name. For example:

(define (only-bigger threshold lon)

(local [(define (pred n)

(> n threshold))]

(filter pred lon)))

;; Is equivalent to

(define (only-bigger threshold lon)

(filter (lambda (n) (> n threshold)) lon))

- Lambda in Dr. Racket can be written by using

(lambda ... )or CTRL \

Sudoku Solver

Template Blending

Combine the templates found in the domain analysis for sudoku solver: Generate an arbitrary-arity tree and backtrack search over it.

(Board -> Board or false)

;; Produce a solution for bd; or false if bd is unsolvable

;; Assume given bd is valid

(define (solve bd)

(local [(define (solve--bd bd)

(if (solved? bd)

bd

(solve--lobd (next-boards))))

(define (solve--lobd lobd)

(cond [(empty? lobd) false]

[(local [(define try (solve--bd (first lobd)))]

(if (not (false? try))

try

(solve--lobd (rest lobd))))]))]

(solve--bd bd)))

Here there were two functions wished for: solved? and next-boards

(@signature Board -> Boolean)

;; Produce true if the board is solved.

;; Assume board is valid, so it is solved if it is full

; (define (solved? bd) false) ; stub

(@signature Board -> (listof Board))

;; Produce list of valid next boards from board.

;; Finds first empty square, fills it with Natural [1,9], keeps only valid boards

; (define (next-boards empty))

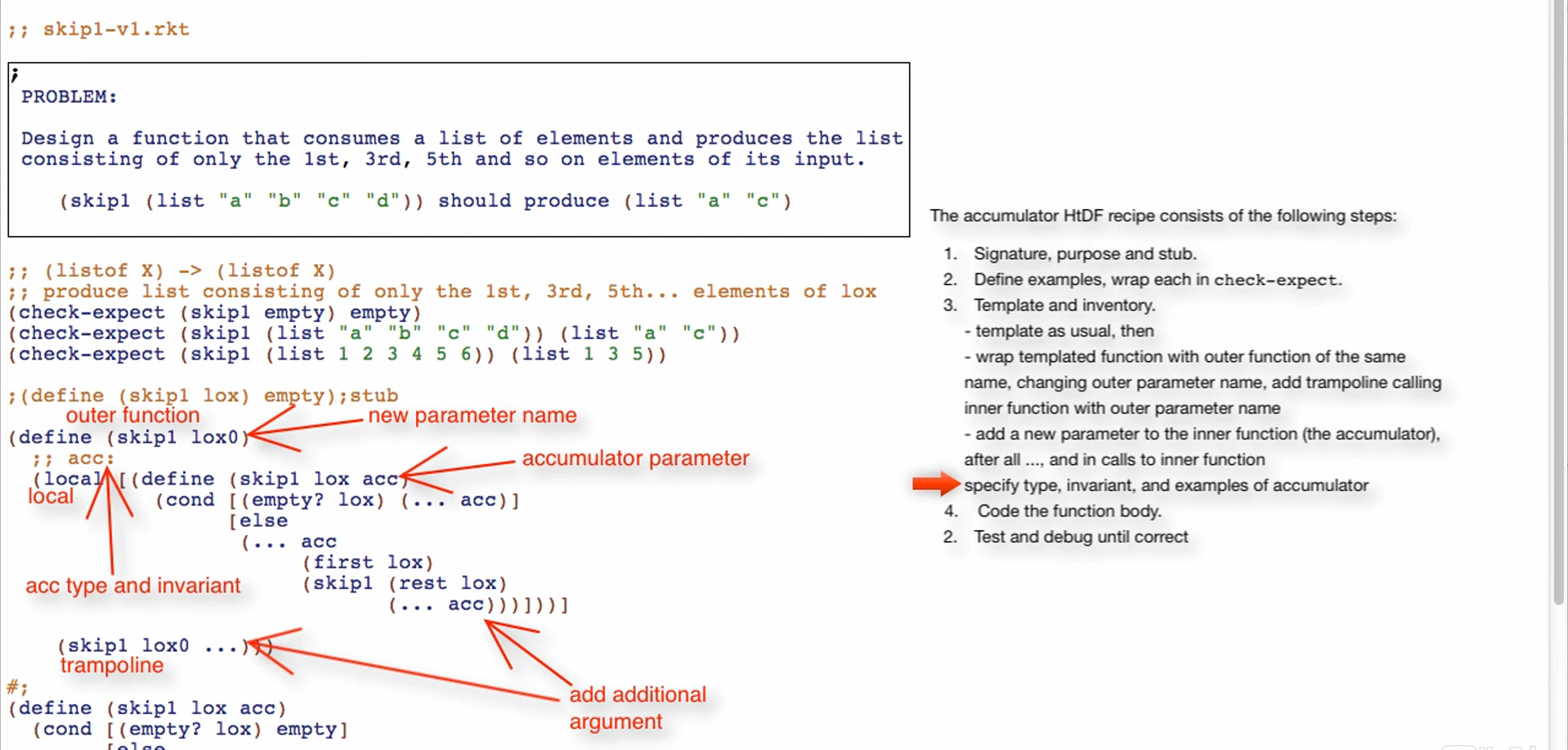

Accumulators

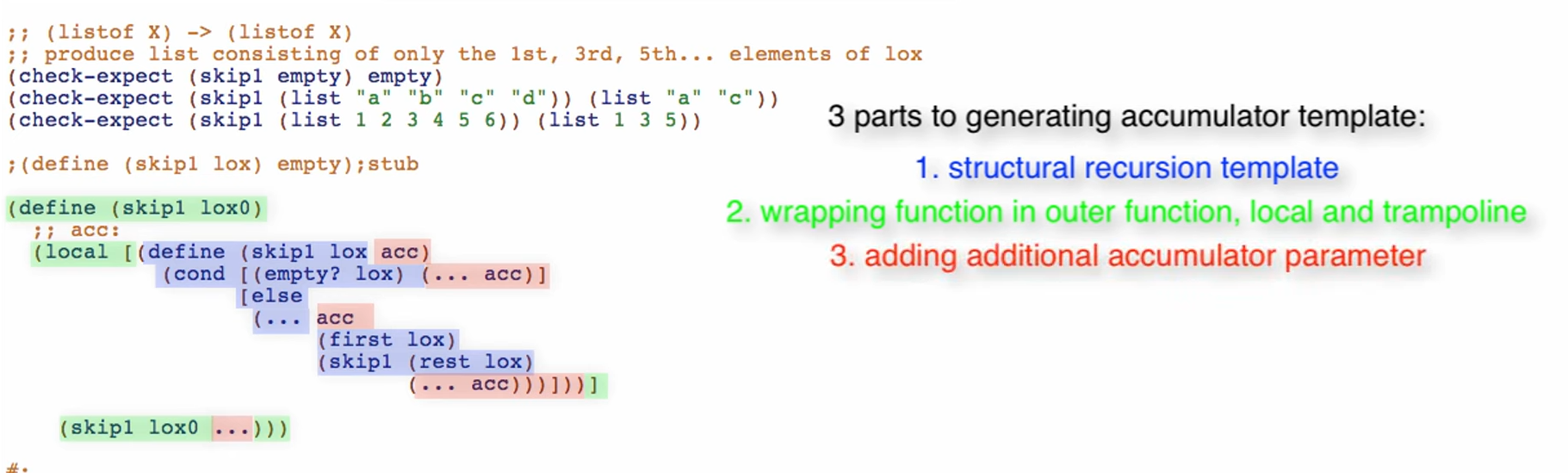

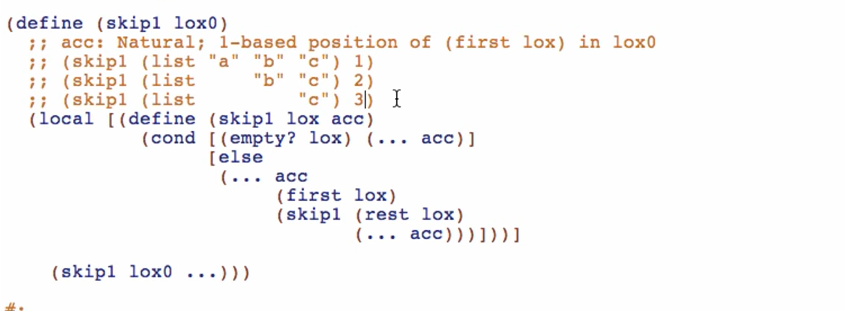

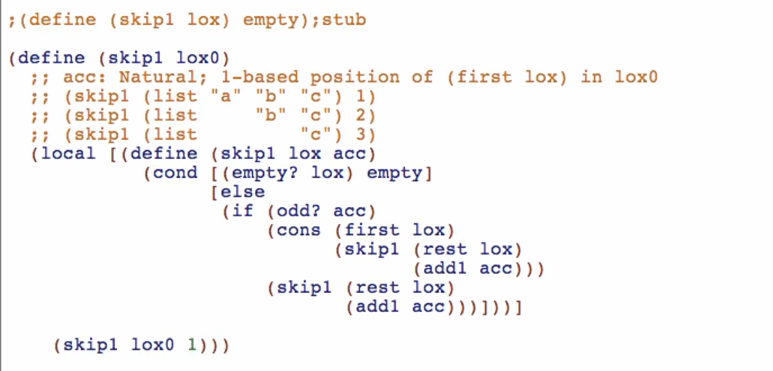

Context Preserving Accumulators

These kinds of accumulators typically maintain the position/index of a data type that can be represented by a list. Take the function skip:

(@htdf skip)

(@signature (listof X) -> (listof X))

;; Produce list consisting of only the 1st, 3rd, 5th, ... elemetns of lox

(check-expect (skip "a" "b" "c" "d") (list "a" "c"))

(check-expect (skip 1 2 3 4 5 6) (list 1 3 5))

(define (skip lox) empty); stub

(define (skip lox)

(cond [(empty? lox) empty]

[else

(if (odd? POSITION-OF-FIRST-LOX)

(cons (first lox)

(skip (rest lox))

(skip (rest lox))))]))

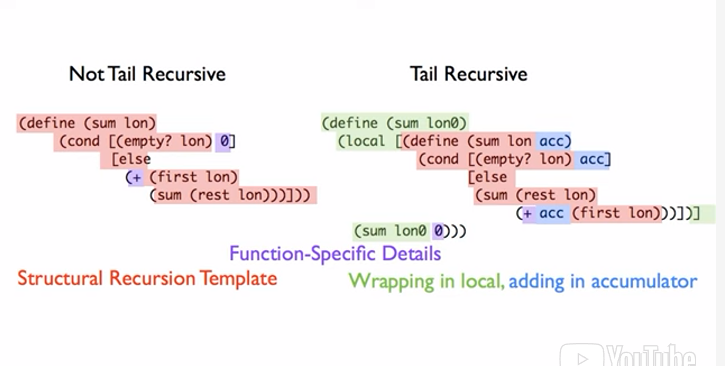

Tail Recursion (result-so-far accumulators)

A function is tail recursion when it is not encapsulated by another function. Take the following, equivalent definitions for sum.

The main difference that makes sum tail recursive in the second is the position of the recursive call. By placing it at the “front” of the else condition answer, it does not need to store the context of (+ 1 (+ 2 (+ 3 (+4 ...) it simply does (+ n (n-1 (n-2 ...) the reason why this works is because the innermost operation is done first, from the inside out.

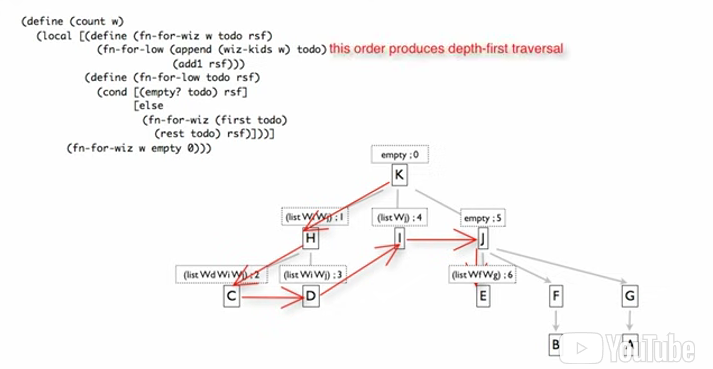

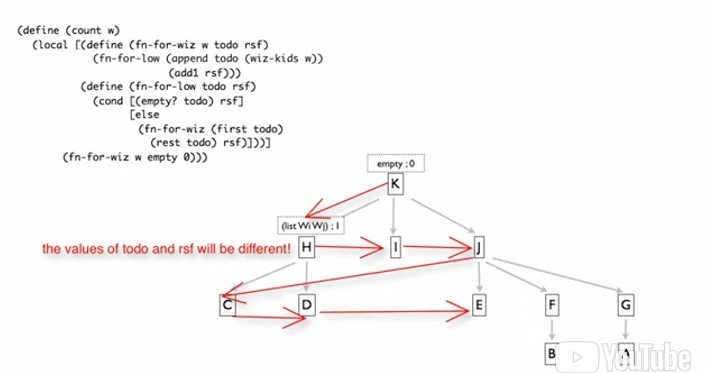

Worklist Accumulators

Worklist accumulators keep track of previous path: they help achieve tail recursion by eliminating the need to retain future recursive calls in pending operations. !!! Every mutual recursive call must be in tail position.

** Depending on the order of the appending the todo, the graph is traversed: BFS vs DFS.

** Depending on the order of the appending the todo, the graph is traversed: BFS vs DFS.

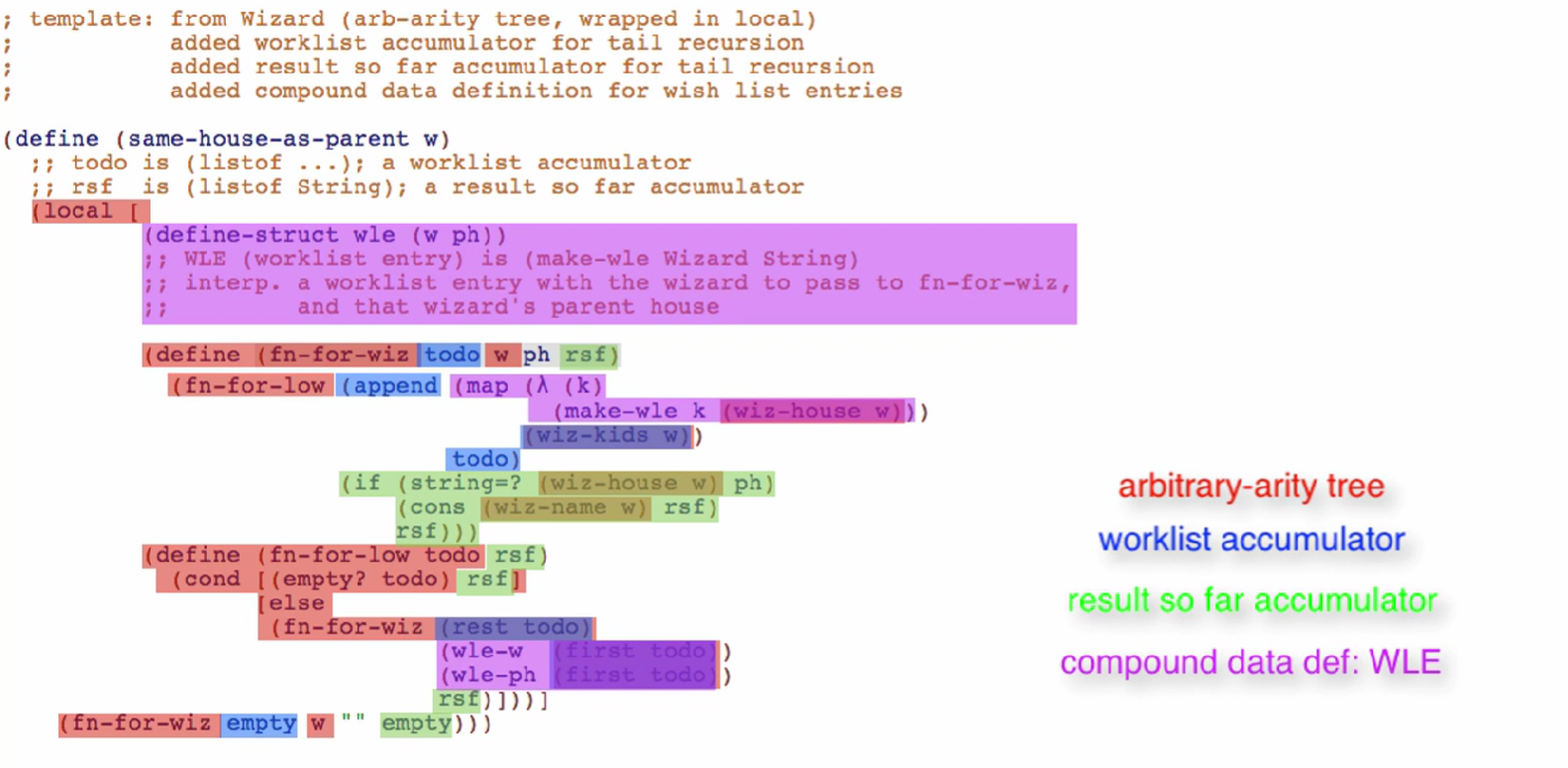

In order make worklist accumulators preserve their context, compound data must be used.

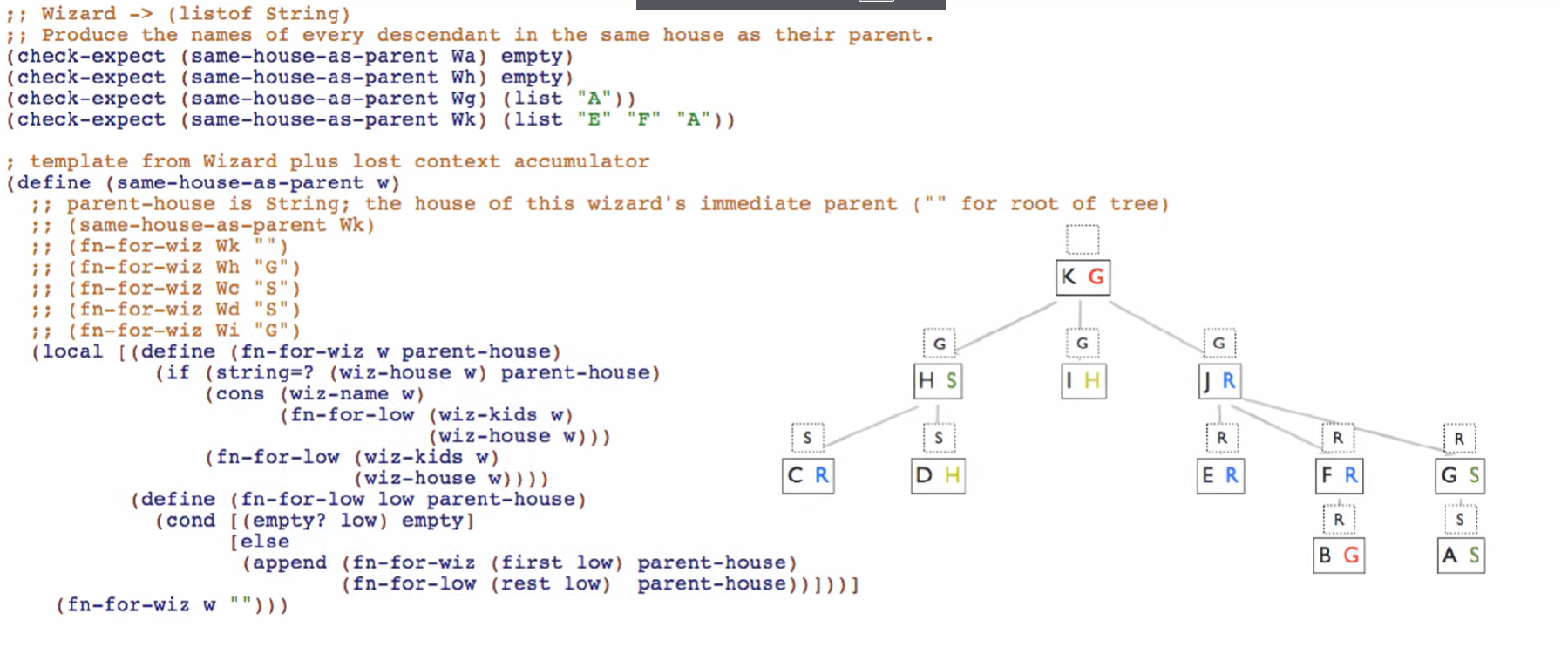

;; Wizard -> (listof String)

;; add worklist accumulator

;; added result so far accumulator for tail recursion

;; added compound data def for wish list entries

(define (same-house-as-parent w)

;; todo is a worklist accumulator

;; rsf is (listof String); a result so far accumulator

(local [(define-struct wle (w ph))

;; WLE (worklist entry) is (make-wle Wizard String)

;; interp. a worlist entry with the wizard to pass to fn-for-wiz,

;; and that wizard's parent house.

(define (fn-for-wiz todo w ph rsf)

(fn-for-low (append (map (lambda (k)

(make-wle k (wiz-house w)))

(wiz-kids w))

todo)

(if (string=? (wiz-house w) ph)

(cons (wiz-name w) rsf)

rsf)))

(define (fn-for-low todo rsf)

(cond [(empty? todo) rsf]

[else

(fn-for-wiz (rest todo)

(wle-w (first todo))

(wle-ph (first todo))

rsf)]))]

(fn-for-wiz empty w "" empty)))

Steps:

- Template from data definition

- Add worklist accumulator

- Add result so far accumulator4. Pass x and context accumulator to

fn-for-x - Map context accumulator to a compound data definition with x

- Append ^ to todo

- Write filtering behavior

- Fill in

rsfand initialize compound components, rsf and todo.

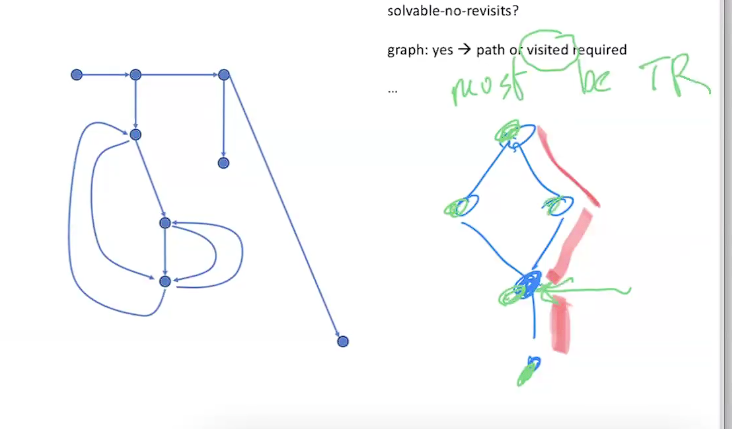

Graphs

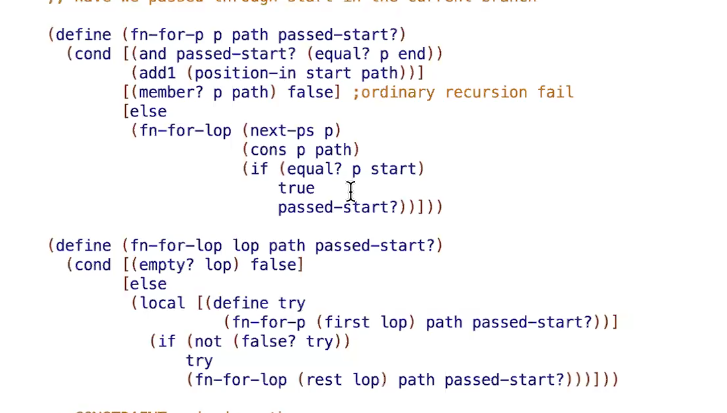

Path Accumulators

When trying to keep track of a node from a root (or other node), keeping track of the paths taken prevents the same path being taken (looping). Think of these as bungee cords that come from a root and try to find a route.

- Original recursion - current branch of the data is in the past

- Prevents cycles (A leads to B and B leads to A)

(local [(define R (sqrt (length m)))

;; trivial:

;; reduction:

;; argument:

(define (fn-for-p p path passed-start?)

(cond [(equal? p end) (add1 (position-of start path))]

;if end is reached, then find the distance between start/path

;[(solved? p) false]

[(member? p path) false] ;termination condition/result

[else

(if (equal? p start)

(fn-for-lop (next-ps p) (cons p path) true)

; if the starting node has been found, pass true as acc

(fn-for-lop (next-ps p) (cons p path) passed-start?))]))

; if the starting node is yet to be found pass acc

(define (fn-for-lop lop path dist)

(cond [(empty? lop) false]

[else

(local [(define try (fn-for-p (first lop) path dist))]

(if (not (false? try))

try

(fn-for-lop (rest lop) path dist)))]))

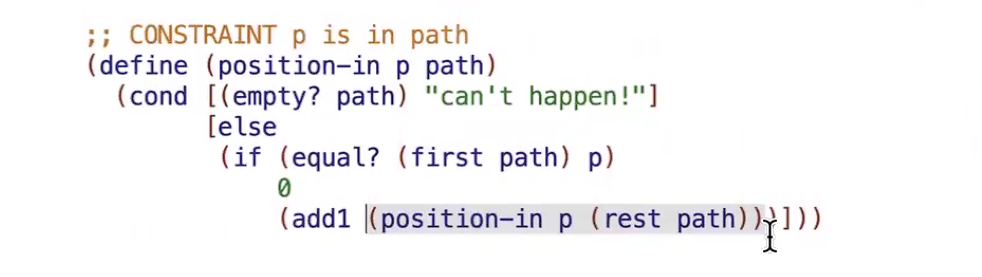

;; CONSTRAINT: p is in lop

(define (position-of p lop)

(cond [(empty? p) (error "p was not in lop")]

[else

(if (equal? p (first lop))

0

(add1 (position-of p (rest lop))))]))

...

(fn-for-p (make-pos 0 0) empty false)))(Full Code)

(local [(define R (sqrt (length m)))

;; trivial:

;; reduction:

;; argument:

(define (fn-for-p p path passed-start?)

(cond [(equal? p end) (add1 (position-of start path))]

;if end is reached, then find the distance between start/path

;[(solved? p) false]

[(member? p path) false] ;termination condition/result

[else

(if (equal? p start)

(fn-for-lop (next-ps p) (cons p path) true)

; if the starting node has been found, pass true as acc

(fn-for-lop (next-ps p) (cons p path) passed-start?))]))

; if the starting node is yet to be found pass acc

(define (fn-for-lop lop path dist)

(cond [(empty? lop) false]

[else

(local [(define try (fn-for-p (first lop) path dist))]

(if (not (false? try))

try

(fn-for-lop (rest lop) path dist)))]))

;; CONSTRAINT: p is in lop

(define (position-of p lop)

(cond [(empty? p) (error "p was not in lop")]

[else

(if (equal? p (first lop))

0

(add1 (position-of p (rest lop))))]))

;; Pos -> Boolean

;; produce true if pos is at the lower right

(define (solved? p)

(and (= (pos-x p) (sub1 R))

(= (pos-y p) (sub1 R))))

;; Pos -> (listof Pos)

;; produce next possible positions based on maze geometry

(define (next-ps p)

(local [(define x (pos-x p))

(define y (pos-y p))]

(filter (lambda (p1)

(and (<= 0 (pos-x p1) (sub1 R)) ;legal x

(<= 0 (pos-y p1) (sub1 R)) ;legal y

(open? (maze-ref m p1)))) ;open?

(list (make-pos x (sub1 y)) ;up

(make-pos x (add1 y)) ;down

(make-pos (sub1 x) y) ;left

(make-pos (add1 x) y))))) ;right

;; Maze Pos -> Boolean

;; produce contents of maze at location p

;; assume p is within bounds of maze

(define (maze-ref m p)

(list-ref m (+ (pos-x p) (* R (pos-y p)))))]

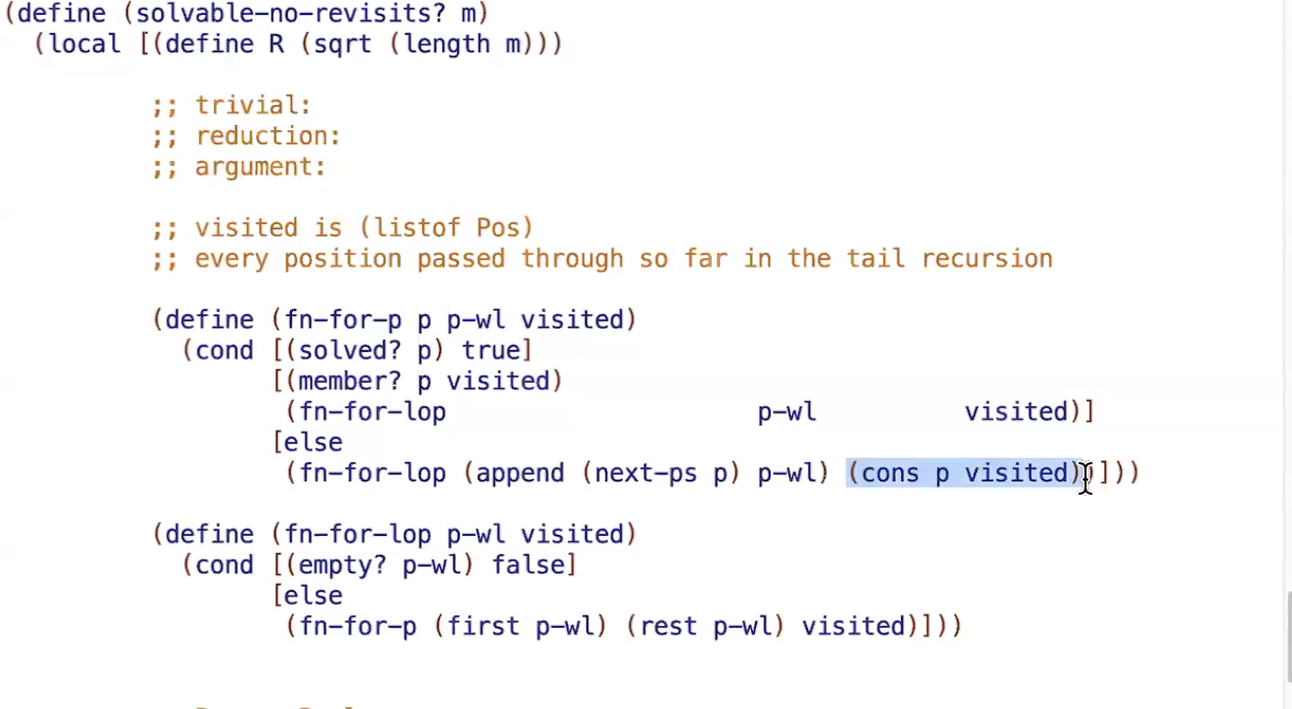

(fn-for-p (make-pos 0 0) empty false)))Visited Accumulators

When trying to keep track of all the nodes that have been checked, visited prevents … . This is similar to spray paint where if a node has already been “visited,” the program proceeds to the next node. This prevents

- Tail recursion - every node visited in the computation

- Prevents cycles and joins (two paths to the same node)

(define (solvable-no-revisits? m)

(local [(define R (sqrt (length m)))

;; trivial: ...

;; reduction: ...

;; argument: ..

(define (fn-for-p p p-wl visited)

(cond [(solved? p) true] ;is condition met?

[(member? p visited) (fn-for-lop p-wl visited)]

;if path has been visited, skip by "ignoring" current p by:

; 1. not adding p to visited accumulator

; 2. not adding p's children to worklist accumulator

[else

(fn-for-lop (append (next-ps p) p-wl) (cons p visited))]))

(define (fn-for-lop p-wl visited)

(cond [(empty? p-wl) false]

[else

(fn-for-p (first p-wl) (rest p-wl) visited)]))

; tail recursive to record all nodes visited.

...1

(fn-for-p (make-pos 0 0) empty empty)))

(Full code)

(local [(define R (sqrt (length m)))

;; trivial:

;; reduction:

;; argument:

(define (fn-for-p p p-wl visited)

(cond [(solved? p) true] ;is condition met?

[(member? p visited) (fn-for-lop p-wl visited)]

;if path has been visited, skip by "ignoring" current p by:

; 1. not adding p to visited accumulator

; 2. not adding p's children to worklist accumulator

[else

(fn-for-lop (append (next-ps p) p-wl) (cons p visited))]))

(define (fn-for-lop p-wl visited)

(cond [(empty? p-wl) false]

[else

(fn-for-p (first p-wl) (rest p-wl) visited)]))

; tail recursive to record all nodes visited.

;; Pos -> Boolean

;; produce true if pos is at the lower right

(define (solved? p)

(and (= (pos-x p) (sub1 R))

(= (pos-y p) (sub1 R))))

;; Pos -> (listof Pos)

;; produce next possible positions based on maze geometry

(define (next-ps p)

(local [(define x (pos-x p))

(define y (pos-y p))]

(filter (lambda (p1)

(and (<= 0 (pos-x p1) (sub1 R)) ;legal x

(<= 0 (pos-y p1) (sub1 R)) ;legal y

(open? (maze-ref m p1)))) ;open?

(list (make-pos x (sub1 y)) ;up

(make-pos x (add1 y)) ;down

(make-pos (sub1 x) y) ;left

(make-pos (add1 x) y))))) ;right

;; Maze Pos -> Boolean

;; produce contents of maze at location p

;; assume p is within bounds of maze

(define (maze-ref m p)

(list-ref m (+ (pos-x p) (* R (pos-y p)))))]

(fn-for-p (make-pos 0 0) empty empty)))BFS vs. DFS

Everything but big band,

Unlikely for htdf module 1 problem (6 and on)

Everything but big band,

Unlikely for htdf module 1 problem (6 and on)

Problems that build off of PSET 9-11

Problems that build off of PSET 9-11