2024-07-1519:18 Status:IBnotes

3.0 History of the periodic table

Gaps were left in the periodic table as Mendeleev believed that there should be an element between two, and filled them in once they were discovered.

3.1 The periodic table

The modern periodic table

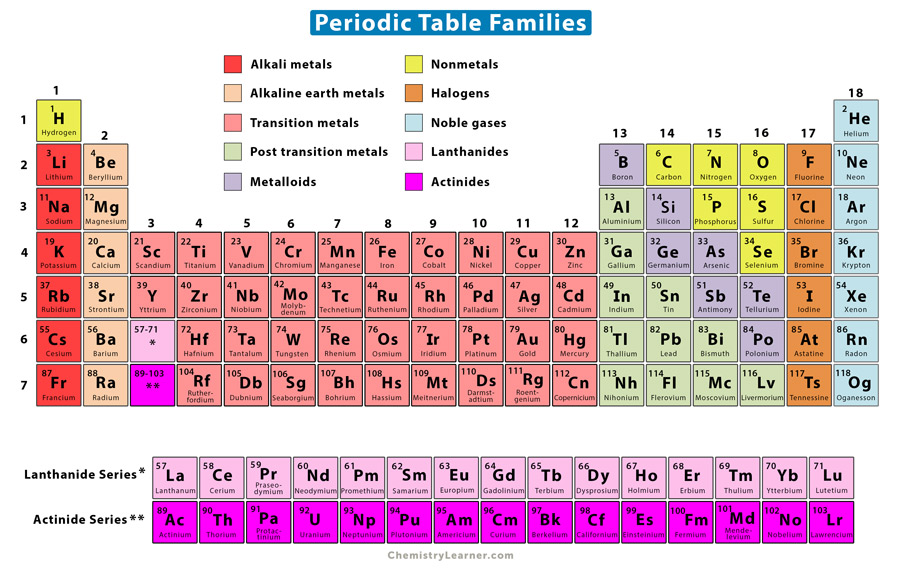

The periodic table is organized such that the following characteristics can be determined by their position on the periodic table.

- The elements are arranged in order of increasing atomic number

- There is a division between metals and non-metals.

- The metallic elements are located left of the division, having a relatively low amount of valance electrons.

- Non metals are on the right of the division, having a relatively high amount of valance electrons.

- Vertical columns, groups are distinguished using roman numerals, I to VIII (skipping transition metals) - IB uses 1 to 7 and group 0 being VIII. (IUPAC uses 1-18 to include the transition metals)

- Horizontal rows are the periods and are numbered 1 through 7. An element belongs to a period that matches the number of its outer shell, n. Elements in the same period have the same amount of ‘shells’ occupied by electrons.

- Hydrogen doesn’t fit neatly anywhere on the periodic table, but is typically found in group 1.

- The group number of an element is the amount of valance electrons it has. (up to Z =20 for SL)

- Group 1 metals for instance, all have 1 valance electron.

- Electron configuration and valance electrons are reserved for HL

3.2 Physical properties of the elements:

*This does not apply too well to transition metals.

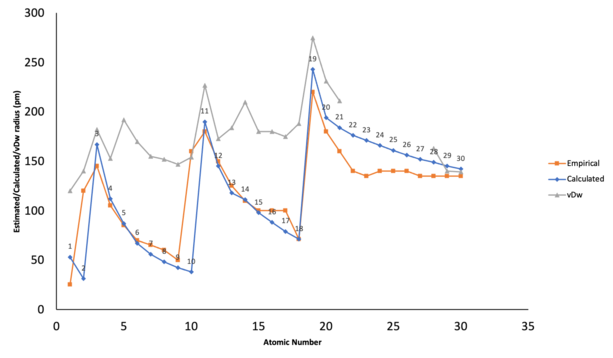

Physical properties such as atomic radii, first ionization energies and melting points are examples of physical properties that experience periodicity, a repeating pattern or trend on the periodic table. A physical property is a characteristic that can be found without changing the chemical composition. For example, the melting point of an element can be found by determining the temperature at which it turns from a solid to a liquid. The element doesn’t chemically change.

Atomic trends

The Periodic Table and Periodic Trends

The Periodic Table and Periodic Trends

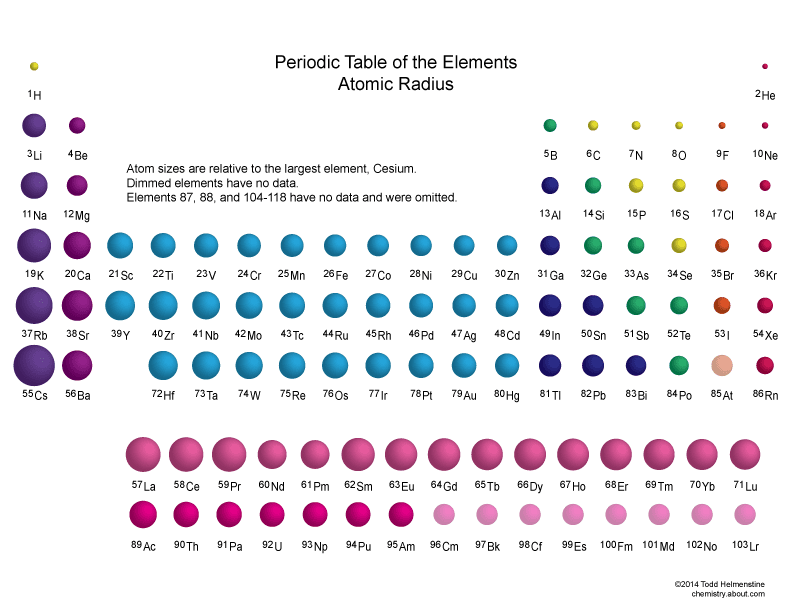

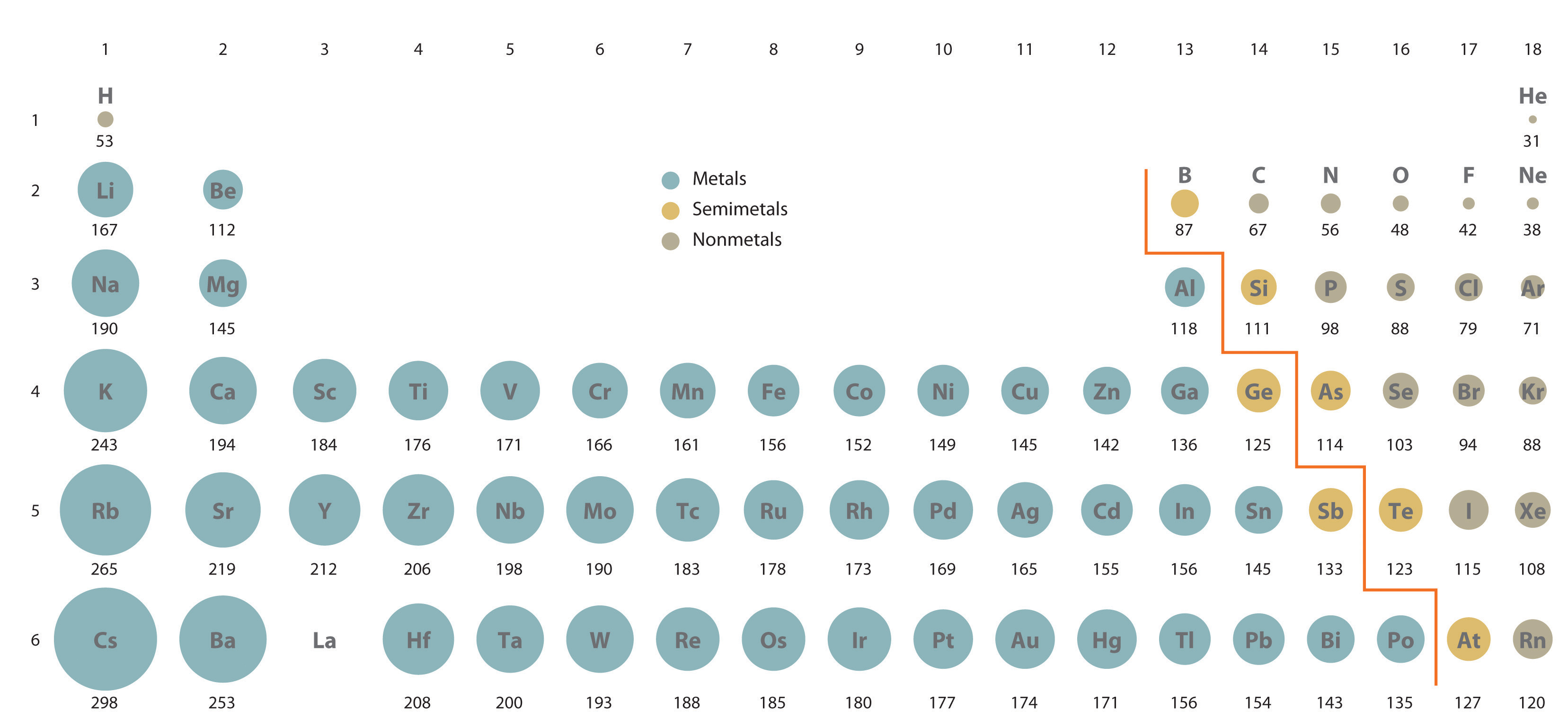

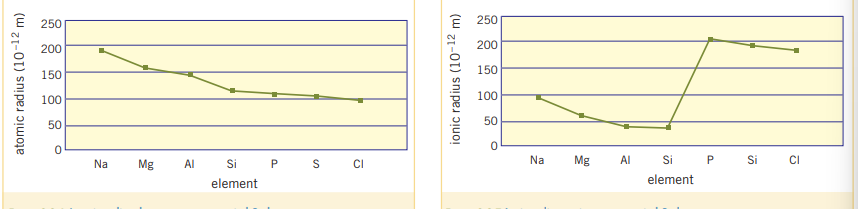

Atomic radius, AR

Atomic radius is the distance from the center of the nucleus to the outermost region. This is measured by the distance between two adjacent atomic nuclei. The metallic radius is the size of an

- The Bohr model has orbits, thus the radius can be measured easily however, we know that this model is highly simplistic as electrons are found in orbitals.

- The way to find the radius is to measure the distance between two atoms in a diatomic molecule, and divide the distance between them by two; .

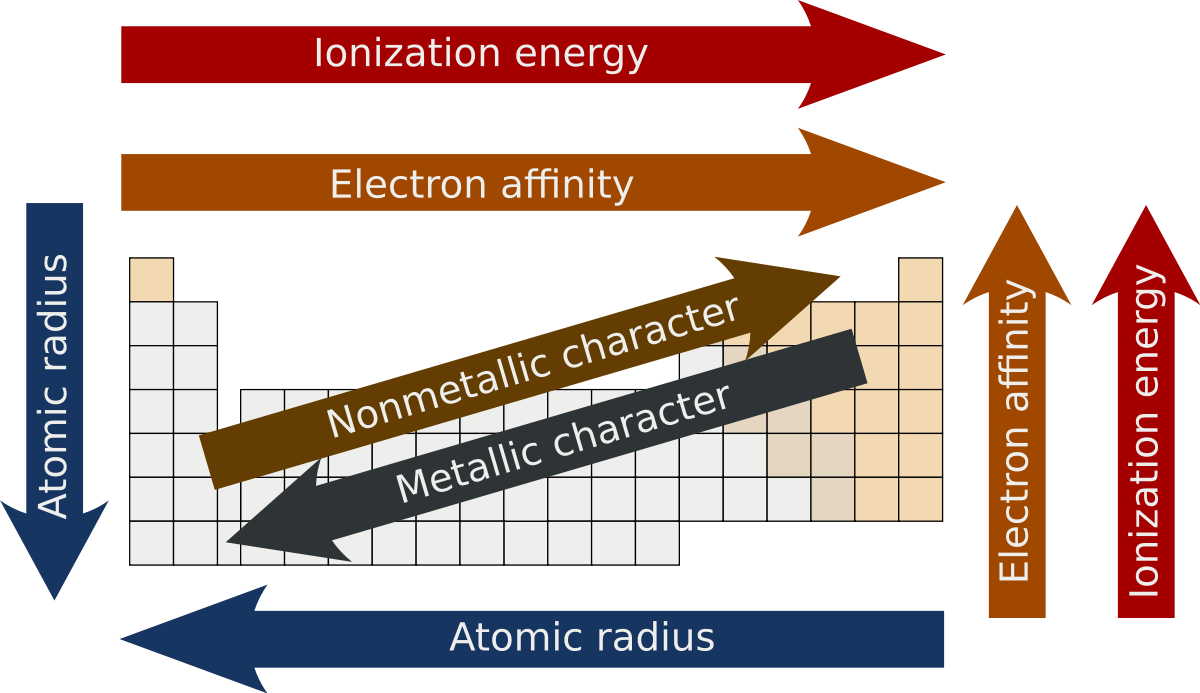

- The atomic radius increases as the effective nuclear charge, increases as the electrons get closer to filling their ‘shell’. A higher results in a higher attraction, pulling the electrons closer to the nucleus. (Where is the net positive charge from the nucleus that an electron can ‘feel’ attractions from. The core electrons are said to shield the valence electrons from the full force of the protons)

- The atomic radius increases down the group from top to bottom as there are more shells ‘blocking’ the valence electrons from the nucleus, This results in the outer shell being further from the nucleus and having a larger atomic radius.

Ionization energy, IE

Ionization energy is the energy required to remove the highest energy electron from a neutral atom. And has the opposite correlation to electron affinity, EA and atomic radius, AR. (First ionization energy). Additionally, ionization energy increases with electronegativity as the more energy required to take away an electron strongly attracted to its nucleus, the more energy is going to be require to take it away.

- In general, ionization energy increases across the period and decreases down a group.

- Across a period, increases as electron shielding remains constant. This pulls the electron cloud closer to the nucleus and strengthens the nuclear attraction to the outer-most electron. This make it more difficult to the (Additionally because the AR is smaller, and held more tightly there is a ‘higher attraction’. This lends to the the electrons being held more tightly and requiring more energy to be taken off)

- Down a group, the number of energy levels increase and the distance is greater between the nucleus and the highest energy electron. The increased weakens the nuclear attraction to the outer-most electron, and is easier to remove.

The first ionization energy is the energy required to remove the highest energy electron (1 electron). This can be represented as

Electronegativity

Electronegativity is the measure of the ability of an atom in a bond to attract electrons to itself.

In general, metals have few electrons in their outermost shell, and consequently lose tend to lose their electrons in reactions. Because of this they have a low electronegativity i.e. they are more willing to give up electrons than to hoard them. Non metals have an opposite tendency, the reason for this is outline below.

- Electronegativity increases across a period and decreases down a group; similarly to the trends of ionization energy, IE.

- Towards the left of the table, valance shells are less than half full, so these atoms (metals) tend to lose electrons and have a low electronegativity (meaning they would rather give off their highest energy electron than take another). Consequently, towards the right of the table, valance shells are more than half full and have a tendency to gain electrons and complete their shell.

- Down a group, the number of energy levels increases, and so does the distance between the nucleus and the outermost orbital. The increased distance and the increased shielding weaken nuclear attraction. Thus the atom cannot attract electrons as effectively. (As the atomic radius increases, electronegativity decreases)

- Fluorine is the most electronegative element whereas (Eka)francium has the least electronegative attraction.

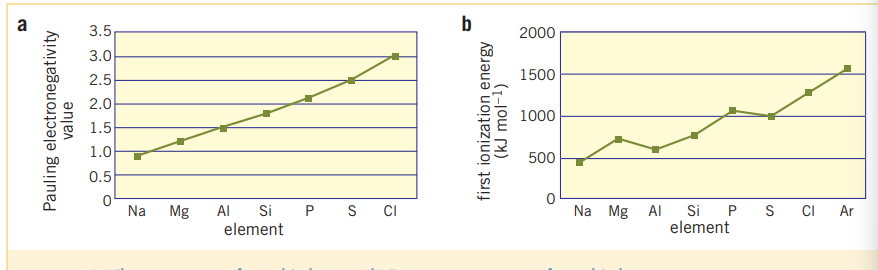

Trends across period 3

Properties of elements within periods are more variable than properties within groups. This can be seen in the following graphs:

3.3 Chemical Properties of elements and their oxides

Just as the physical properties exhibit a periodicity, within groups and periods, so do the chemical properties of the elements and some of their compounds. The chemical properties relate to the electron arrangement of the elements.

Trends in chemical properties within a group

Because the alkali metals have a low ionization energy and electronegativity, they are violently reactive to the point where they need to be stored in oil (As they react with water). The reactivity of alkali metals increase down the group. The easier a substance loses electrons the better a reducing agent they are (lr), similarly the better a substance is at taking electrons, the better oxidizing agent they are, (go); explored more in unit 10. The halogens get more reactive as the period number decreases, making fluorine the most reactive halogen, the most oxidizing agent.

The oxides of period 3 elements

All the period 3 elements react with oxygen and depending on the electronegativity of the period 3 element, the nature of the aqueous solution changes. For instance, and are both acidic as they are ionic whereas and are both alkaline as they are covalently bonded. When the oxides react with water, the ease at which they produce The more metallic in nature a period 3 element is the stronger it acts as an acid, the more non-metallic, the more alkaline it acts. This forms a kind of spectrum where metalloids such as aluminum are amphoteric, acting both as an acid and a base.

Alkaline reactions:

Acidic ration

Amphoteric reactions:

- Acting as a base:

- Acting as an acid:

Periodic Trends (Chemistry 25 Review)

The size of an atom is defined to be one half of the distance between two adjacent atomic nuclei (atomic radii). Metallic radius is the size of an atom in a solid crystal structure of the element (metallic bonds). Covalent radius is the radius of molecular compound (bonding distance). Note that trends do not hold very well for transition metals.

Effect of Energy Levels

As in an atom increases, the outer move further from the nucleus (As we move down a period, atomic radius increases).

Effects of Atomic Number

As atomic number increases, the number of protons in the nucleus increases, and there is a stronger electrostatic pull. (as we go across a period atomic size decreases).

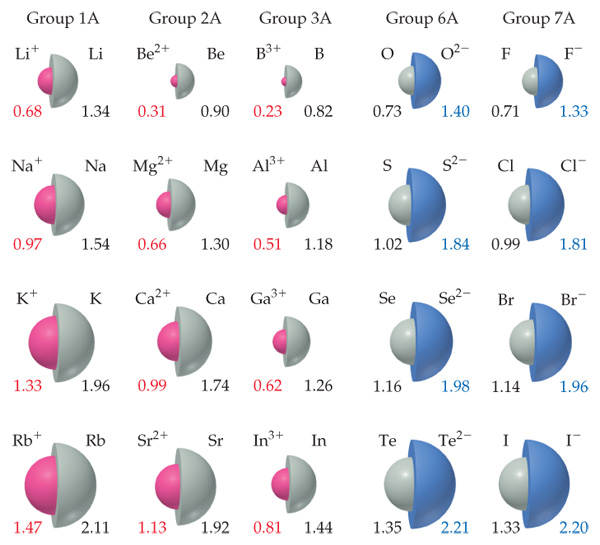

Ion Size

Cations will always be smaller than their atoms, and anions will always be bigger than their atoms. This is because cations have a full shell, which is more stable and ‘holds’ electrons closer, as it lost electrons not in their shell. Whereas anions have more elections, experience electron repulsion and have a new shell taking up space.

Trends in Electronegativity

Elements with smaller radii have stronger electronegativity.

Trends in Ionization Energy (Bond Breaking)

Ionization energy is the energy required to remove an electron and make the atom have a positive charge. This is fore one mole of electron from one mole of gaseous atom/ions.

The first ionization energy is removing one electron from the highest energy level

The second ionization energy is the energy require to remove the next highest energy electron. This is always larger than the first ionization energy as it is at a lower level. This also could be very high relative to the first ionization energy (depending on the substance).

Trends in Electron Affinity (Bond Forming)

Electron affinity is the energy required or gained when adding an electron. This is similarly for 1 mole of electrons to one mole of gaseous atoms/ions. In most cases, is negative because energy is released when the electron is added. For the second electron affinity, , the value is positive as the electron is being added to an atom/ion that already has a 1- charge.

Period 3 Oxides

Metal oxides are basic, non-metal oxides are acidic. \begin{gather} Na_2O_{(s)} +H_2O_{(l)} \rightleftharpoons2Na^+_{(aq)}+2OH^-_{(aq)} \\ MgO_{(s)} + H_2O_{(l)} \rightleftharpoons Mg^+_{(aq)} + 2OH^-_{(aq)} \end{gather}

Less basic With it can act as both an acid and as a base - it is amphoteric.

\begin{gather} Al_2O_{3(s)} + 6HCl_{(aq)} \rightleftharpoons 2AlCl_{3(aq)} + 3H_2O_{(l)} \\ Al_2O_{3(s)} + 6HCl_{(aq)} \rightleftharpoons 3H_2O_{(l)} + NaAl(OH)_{4(aq)} \end{gather}

neither an acid nor base naturally, but can function as a weak acid in the presence of a strong base at a high temperature.

Non-metal Oxide List:

Halogen Halides

Halogens reaction exothermically with each other to form interhalogen compound (every binary compound of the 4 common halogens is known). In these cases, the more electronegative halogen has the -1 oxidation state, and the less electronegative halogen has the+1 state. The larger halogens ( can expand their valence shells into unused orbitals and form the central atom for a compound with the formula: .

P3 chlorides as we go across a period become ‘more covalent’, and more acidic:

\begin{gather} SiCl_{4(s)} +3H_2O_{(l)} \to Si(OH)_{4(aq)} +4HCl_{(aq)} \\ PCl_{3(s)} + 3H_2O_{(l)} \to H_3PO_{3(aq)} +3HCl_{(aq)} \\ PCl_{5(s)} + 4H_2O_{(l)} \to H_3PO_{4(aq)} + 5HCl_{(aq)} \end{gather}

*Ignore sulfur chlorides

Transition Metal Properties

Transition elements have properties that differ considerably from the main group elements: Variable oxidation states, forming complex ions (with ligands), make colored compounds, catalytic properties, magnetic properties.

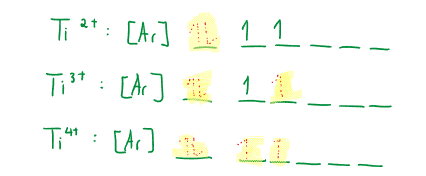

Electron Configuration

Transition elements are defined as elements that contain incomplete d-orbital level (in one or more of their oxidation states). To recall electron configurations: Transition metal examples: Vanadium: , Manganese: , Iron: , ** Chromium: , Copper: . *** Zinc is not considered a transition metal: = full orbital. Transition metals always have an incomplete orbital (or with a full orbital).

Atomic Properties

Moving right across a period in the transition metals size decreases at first, but then remains fairly constant (159, 148, 144, 130, 129, 124, 118, 117, 122). This is because there is relatively small increase in effective nuclear charge, experienced by the outermost .

The extra attraction from the added proton is offset by the extra electron added to the orbital (and its shielding effect). Electronegativity, and ionization energy both follow the same trends for the same reasons.

Oxidation States

Transition metals can have many oxidation states. Because the and electrons have very similar energy and thus are all available for bonding. Both the and orbitals’ electrons can be considered to be valence, and thus can have different electron configurations.

Up to group 7, the highest oxidation state for the element is the same as the group number. Very high oxidation states occur when bonded to highly electronegative elements (e.g. oxygen or fluorine): .

Coordination compounds

Transition elements can form coordination compounds (complexes). There are materials that have a central metal atom, and are bonded to molecules or ions called ligands. A ligand is a molecule or anion, with at lease one lone pair of electrons. The metal cation is attracted to the lone pairs and they form a coordinate covalent bond (dative bond) = a covalent bond, where the electrons only come from one source. Most transition metal ions exist as hexahydrate ions Some ligands include but a more exhaustive list can be found on t.15/16.

Example:

The bond between the water molecule’s oxygen and the iron ion is covalent, where water is acting as the ligand.

Counter ions

A counter ion is an ion that bonds to the central metal atom, and counters its charge while maintaining the complex’s overall structure (ligands are still covalently bonded to the central metal atom). An example of these ions are in or where is acting as the counter ion.

Coordinate Number

The number of ligand attached to the central atom is the coordinate number. The most common is 6, having an octahedral shape. The orientation for 4 is square planar/tetrahedral, and 2 is linear.

Ligands

Ligands are classified in terms of the number of donor atoms they can use to bond to the metal ion. Monodentate ligands only have one donor atom (one bond, and one lone pair). Bidentate ligands have two donor atoms (more=polydentate). An example of a polydentate is EDTA, ethylenediamine tetracetic acid.

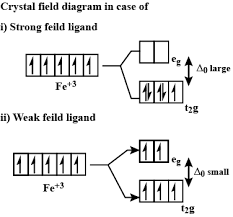

Magnetic Properties

Ferromagnetism is exhibited in materials that can maintain its own magnetic field. Magnetic particles align and create permeant magnetic domains. Some examples include Iron, Nickle and Cobalt. Asides from ferromagnetism, paramagnetic and diamagnetism are there other, weaker forms of magnetism: The orbital splitting observed in transition metals also helps explain its magnetic properties. Paramagnetic substances are attracted to weak magnetic field (mostly unpaired electrons), and diamagnetic substances are repelled by magnetic fields (mostly paired electrons).

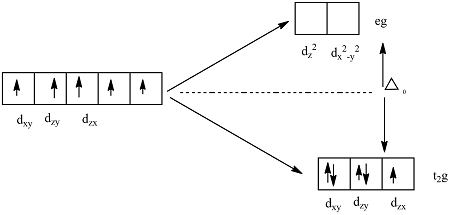

The high spin complex with a weak ligand has many unpair electrons. Because the electrons are in the same orientation, they amplify their magnetic properties. The low spin complex is a result of the many paired electrons who cancel each other’s spin and thus cancel each other’s magnetic field.

The orbital ‘splits’ into and

- to always has a high spin.

- to either has a high spin or a low spin - depends on the field (crystal field split = based on the ligands that are attached to it).

- to always has a low spin.

Transition Metals as Catalyst

Heterogeneous catalysts

Heterogeneous catalysts absorb the molecule on the surface: Hydrogenation: Haber process: Contact process: Catalytic converters:

Homogenous catalysts

Homogenous catalysts are materials that like to bond to the metal ion instead of the ligand. This changes the oxidation state. Used then recycled: E.g. Iron in hemoglobin, cobalt in vitamin

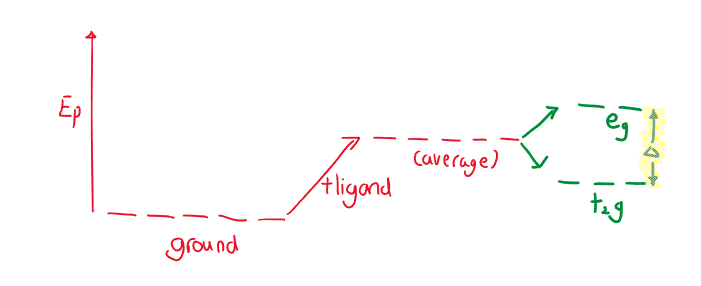

Crystal Field Theory

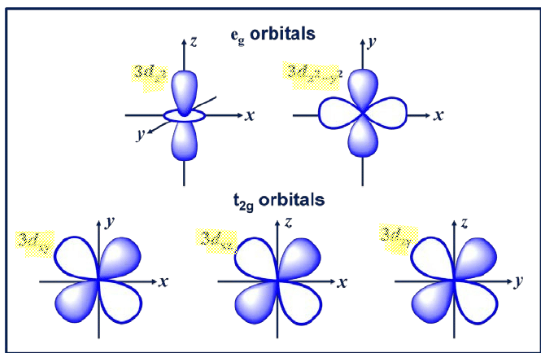

A ligand will cause unfilled orbitals to split into two energy levels. The electrostatic attraction between the metal cation and the negative charge of the ligands form bonds. The ligand approaches the metal, perpendicular to the x, y, and z axes.

As the ligand approaches, there is uneven electron-electron repulsion amongst the d-orbitals. The ligands push down on the and orbitals, which experience a stronger repulsion (high energy orbitals called orbitals). Since the ligands repulse less, they form the lower energy orbitals, called orbitals.

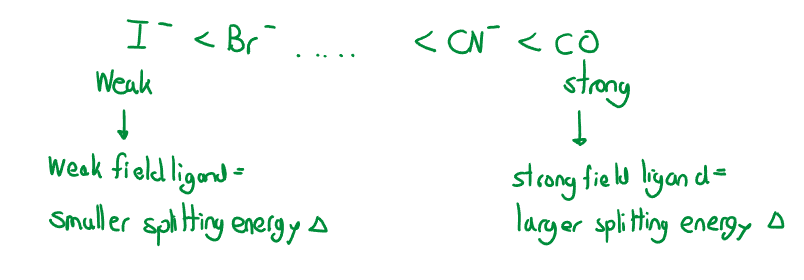

The difference in energy between and orbitals is called the crystal field splitting energy . Differing ligands create crystal fields of differing strengths.

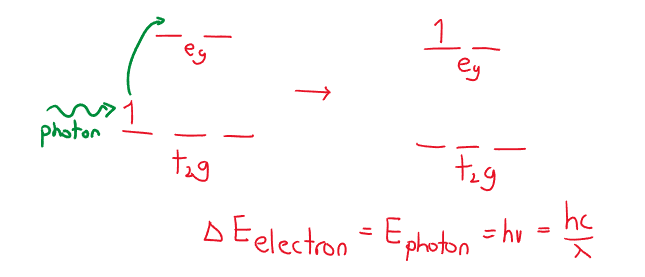

Color

Transition metals appear colored because their ions above absorb some light energies when the orbitals split into sublevels, . The transition metal that would not absorb any light, and would be colorless is as the orbital and orbital are empty. If there are electrons present, in any orbital, there is always potential for the electron to move to a different orbital. For an electron to move from a orbital to a orbital, it needs to absorb a specific energy photon (this absorption creates ion colors).

If an ion absorbs one color is will transmit the rest of the spectrum. We observe the lack/missing wavelength, as the complementary color. (Red-green, orange-blue, yellow-purple). What affects an ion color is the type of ion, oxidation state, type of ligand (which all impact the strength of the field crystal splitting).