2024-07-1402:44 Status:IBnotes

2.0 Intro:

A chemical bond forms when (generally) the outer-shell electrons of different atoms come close enough to each other to interact and rearrange themselves into a more stable arrangement - one with a lower overall chemical potential energy. All chemical bonds are based on the electrostatic attraction between positive and negative particles, protons and electrons. When two or more atoms approach one another to form a bond, it is their outer-shell electrons that generally interact. Outer-shell electrons known as valance electrons.

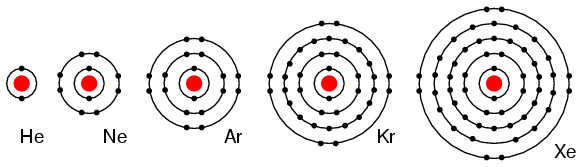

The most stable arrangement of electrons can be found in group 0 (VIII), of the periodic table. As the shell for their respective period is full. As there are no electrons to bond with another atom, they are both stable and generally unreactive. (The Bohr model generally works until calcium. The concept of a full octet, 8 electrons per shell being the most stable configuration, or shell only applies until that point.)

The rearrangement of valance electrons to form chemical bonds tend to result in the formation of very strong bonds. The energy required to break these bonds, the bond dissociation enthalpy is defined as the enthalpy (energy/mol) required to break the bonds of 1 mole of bonded atoms. The larger the value, the stronger the bond.

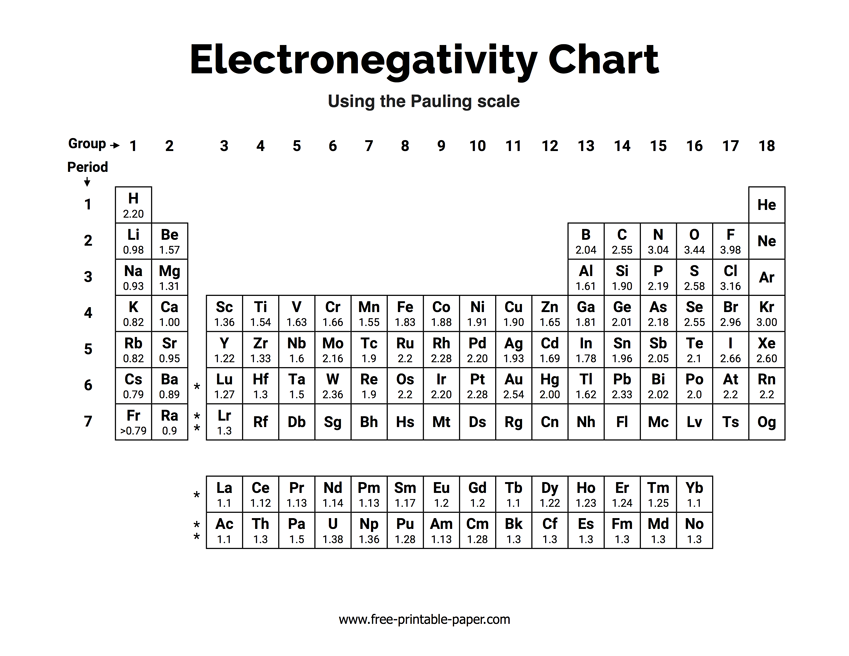

Electronegativity

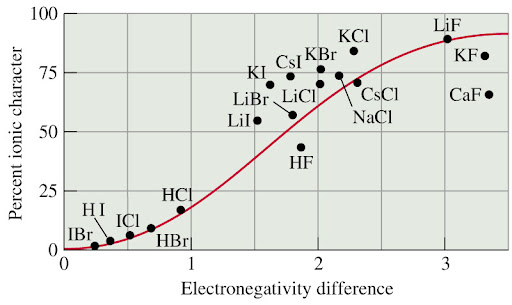

Electronegativity is the tendency for an atom to attract shared electrons (or electron density) when forming a chemical bond. Generally when the difference is large, (often a metal/non-metal) the bond is ionic, contrarily, smaller differences entail a covalent bond. There is no hard cut off between ionic and covalent: as it gets ambiguous higher chemistry needs to be used to differentiate the two kinds of bonds.

Dissociation enthalpy table

| Compound or element and formula | Atom types | Bonding type | Dissociation enthalpy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride, NaCl | Metal/Non-metal | Ionic | 411 |

| Magnesium oxide, MgO | Metal/Non-metal | Ionic | 601 |

| Aluminium fluoride, AlF3 | Metal/Non-metal | Ionic | 1504 |

| Hydrogen, H2 | Non-metal | Covalent | 436 |

| Nitrogen, N2 | Non-metal | Covalent | 945 |

| Water, H2O | Non-metal | Covalent | 285 |

| Sodium, Na | Metal | Metallic | 109 |

| Iron, Fe | Metal | Metallic | 414 |

| Tungsten, W | Metal | Metallic | 845 |

2.1 Ionic bonding

What differentiates ionic compounds from covalent bonding is the electrostatic difference in potential between two atoms. Generally high potentials are ionic and generally low potentials are covalent. There is no hard cut off, and is more of a prediction of nature than anything.

Types of elements:

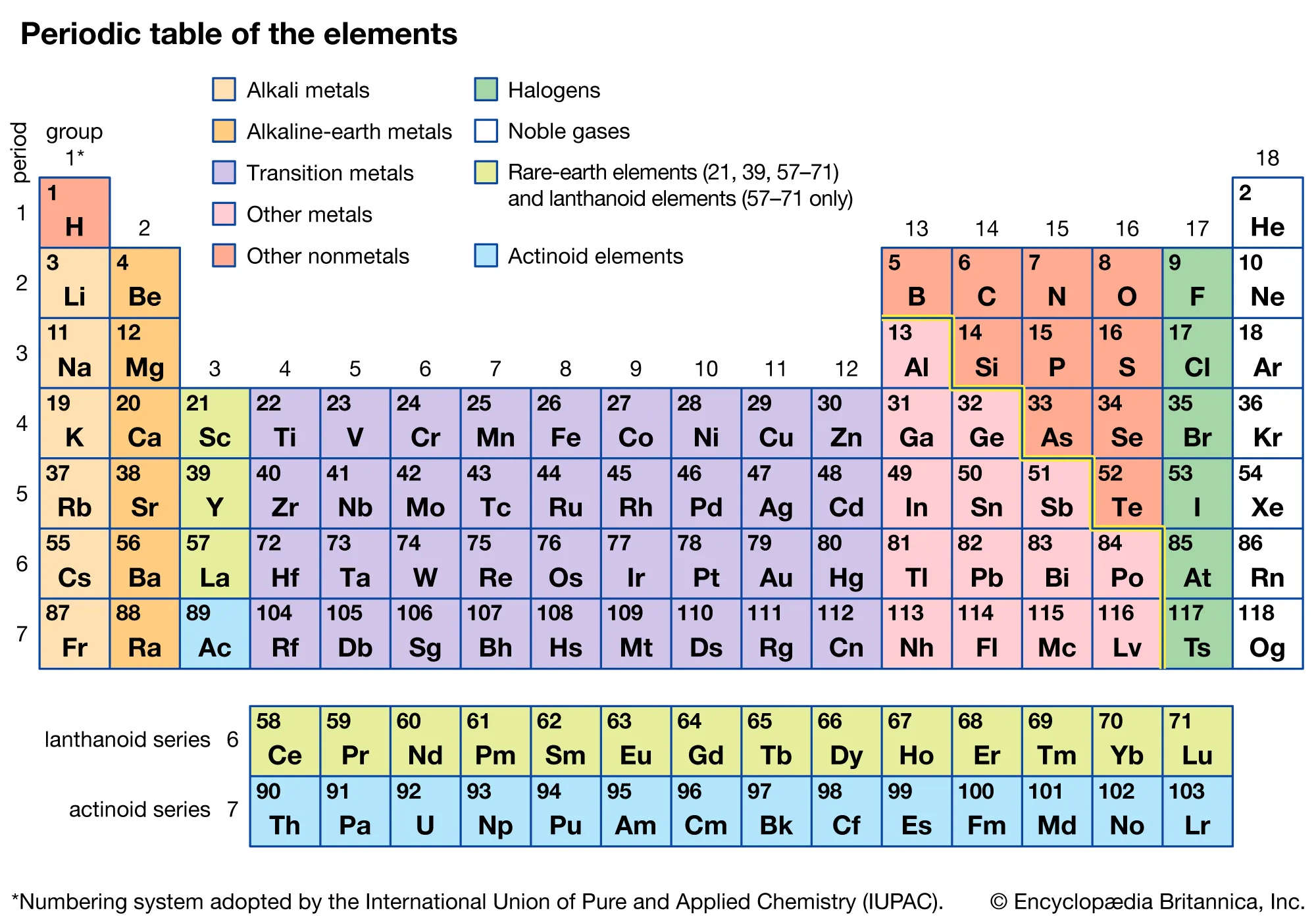

An element is a substance made up of atoms of the same type. The majority of the naturally occurring elements are metals and are found on the leftmost part of the periodic table (except for hydrogen). Non-metals tend to be on the right of the periodic table.

Metallic properties

Metals tend to be shiny; have a high melting point and high boiling point; are good conductors of heat and electricity; sonorous (makes a noise when struck); malleable (can be shaped); ductile (can be drawn into wires); have relatively low amounts of valance electrons and thus tend to give away electrons rather than take electrons to become stable and fill their valance shell.

Non-metallic properties

Non-metals tend to be poor conductors of electricity and heat; have low melting and boiling points (as such several are gaseous at room temperature); have relatively high amount of electrons in their outer shell; and tend to accept electrons rather than give them to become more stable.

The nature of the ionic bond

Ionic bonding occurs as the result of a metal atom donating its valance electron(s) to a non-metal atom. As the metal atom loses electrons, it will gain an overall positive charge, becoming a positively charged atom, a cation. Similarly, the non-metal atom accepts electrons, becoming a negatively charged, anion. An ionic compound has a net 0 charge and the appropriate ratio of anions and cations are required to make it neutral. The lowest ratio, is the empirical formula of the ionic compound.

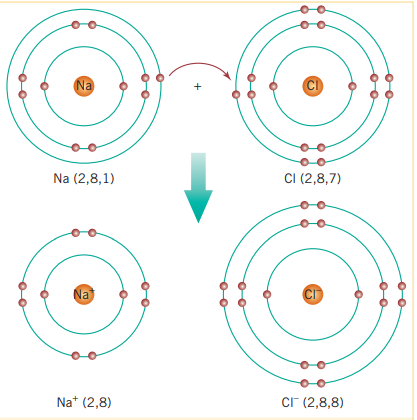

Sodium acts explosively with chlorine gas (this is because the difference in electronegativity is so great) to produce a white crystalline, solid, sodium chloride. This compound is an example of an ionic compound and its electron arrangement is formed as follows:

Notice that sodium’s atomic radius decreases when it becomes an ion. (And because of electron repulsion, the atomic radius of chlorine also gets slightly larger.)

Structure of ionic bonds

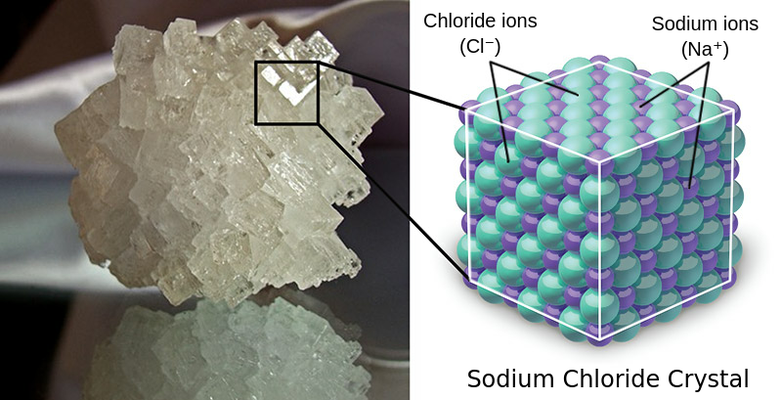

Ionic compounds can be formed by any combination of positive and negative ions. In an ionic lattice a positive ion will always be surrounded by negative ions, and a negative ion will always be surrounded by positive ions. The exact configuration is dependent on the relative sizes, the empirical formula and charges of the ions involved.

Ionic compounds do not exist in nature as separate parts; they arrange themselves into a regular pattern, a lattice structure. In a given sample, there are likely millions of ions that extend in all three dimensions. No fixed number of ions is involved, but the ratio of cations to anions is constant for a given compound, shown in the empirical formula for a given ionic compound.

The most stable arrangement of ions for any particular compound will be one in which the positively charged ions are packed as closely as possible to the negative charge ions, and the ions with the same charge are as far apart as possible. This arrangement serves to maximize the electrostatic attraction and minimize the repulsion between like ions (thus lowering the overall chemical potential)

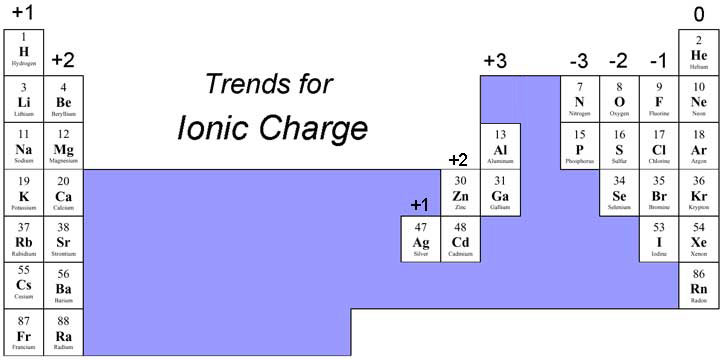

Trends for ionic charge for group 1, 2 and non-metals

Trends for ionic charge for transition metals

Transition metals tend to lose electrons when forming ionic compounds; however, their more complex electron arrangement means that they can generally from more than one type of ion. For instance, iron can form a 2+ charge and a 3+ charge.

Naming and formula conventions for ionic compounds

- When naming an ionic compound, cation is generally written first, followed by the anion. (E.g. Sodium chloride, NaCl) (The exceptions to this are salts of organic acids such as sodium ethanoate, )

- As compounds do not carry an overall charge, it is necessary to balance the charges of the anion and cation components. (E.g. )

- If more than one of each ion is required to balance the overall charge, a subscript is used to indicate the number of each species required. (E.g. )

- In the case of some polyatomic ions, it may be necessary to use brackets to ensure no ambiguity is present. (E.g. )

- For metals that are able to form ions of different charges, roman numerals are used to indicate the relevant charges (E.g. iron (III) chloride would have the formula, and iron (II) chloride would have the formula, )

- the name of the ion depends on its composition. For example, the ending -ate, for a polyatomic ion indicates the presence of oxygen; the ending -ide, indicates that the ion is made up of a single atom with a negative charge, such as

- The name of the ion often gives a clear indication of the atoms present. The hydroxide ion s made up of hydrogen and oxygen, , while hydrocarbonate ions are made up of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen, .

Popular ions (can be found in formula booklet or periodic table)

| +4 | +3 | +2 | +1 | -1 | -2 | -3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tin(IV), Sn 4+ | Aluminium Al 3+ | Magnesium, Mg 2+ | Lithium, Li + | Fluoride, F - | Oxide, O2- | Nitride, N 3- |

| Lead (IV), Pb 4+ | Chromium (III) Cr 3+ | Calcium, Ca 2+ | Sodium, Na + | Chloride, Cl - | Sulphate, SO4 2- | Phosphate, PO4 3- |

| Iron (III) Fe 3+ | Strontium, Sr 2+ | Potassium, K+ | Bromide, Br - | Sulphide, S 2- | ||

| Barium, Ba 2+ | Hydrogen, H + | Iodide, I - | Carbonate, CO3 2- | |||

| Iron (II), Fe 2+ | Copper (I), Cu + | Hydroxide, OH - | Chromate, CrO4 2- | |||

| Copper (II), Cu 2+ | Silver, Ag 1+ | Permanganate, MnO4 - | Dichromate, Cr2O7 2- | |||

| Zinc, Zn 2+ | Ammonium, NH4 + | Cyanide, CN - | Thiosulphate, S2O3 2- | |||

| Lead (II) Pb 2+ | Hydronium H3O + | Hydrogen sulfate HSO4 - | ||||

| Hydrogen carbonate, HCO3 - | ||||||

| Ethanoate ion, Ch3COO - |

Ionic compound properties:

Ionic compounds have a tendency to form crystals; be hard and, brittle; have high melting and boiling points; be non-conductive as solids but conductive when aqueous and molten; often soluble in water and insoluble in nonpolar solvents; have high enthalpies of fusion and vaporization; and when solid are good insulators.

2.2 Metallic bonding

The nature of the metallic bond:

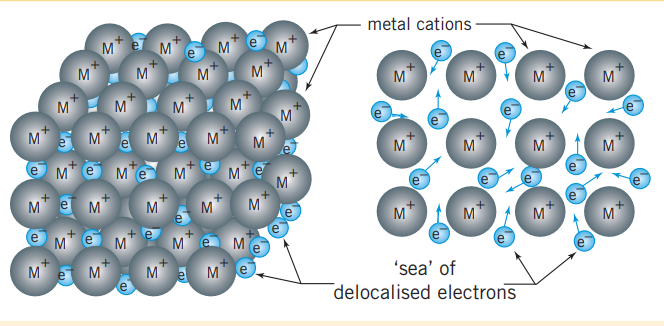

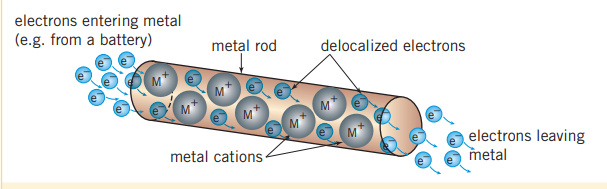

Metal ions are formed when atoms lose their valance electrons, and are arranged in a three-dimensional lattice. This array of ions is surrounded by freely moving electrons, that form a ‘sea’ of valance electrons that are said to be delocalized. This is because they are not confined to a particular location (as ions would be in ionic compounds) and can move throughout the structure. Electrons are attracted to the metal cations and this electrostatic attraction holds the lattice together. This kind of bonding is metallic bonding.

Metals lose their valance electrons to the sea of electrons simply because they achieve greater stability by doing so. Without their valance electrons, they achieve a noble gas configuration.

When non-metals are present, the valance electrons in the sea of electrons are transferred to the non-metal atoms, creating an ionic bond.

Why metals are conductive

Because the sea of delocalized electrons exist throughout the metal in a fluid like state and exist within a discrete ratio with the cations, they experience a specific amount of electron electron repulsion. Thus when electrons are entering forms a battery for instance, electrons will also leave to keep this ratio in tact. This phenomenon is why metals are conductive.

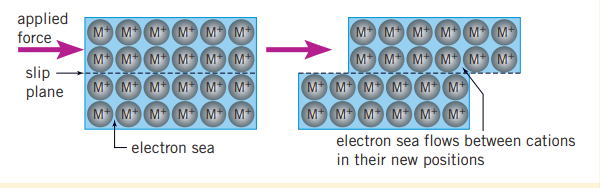

Why metals are malleable/ductile

Malleability is the ability to be beaten into shape without breaking. The delocalized electrons are responsible for maintaining the lattice structure of metals when morphed. When a metal is bent, its lattice of positive ions is displaced, and there is a possibility of ions coming into contact with another cation and repelling each other. The constant movement of the delocalized electrons prevents this from occurring, so the metal bends without breaking.

2.3 Covalent bonding

Chemical bonding

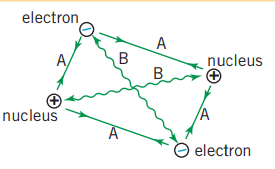

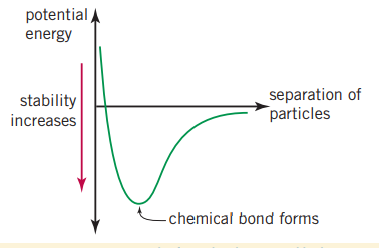

A chemical bond is generally defined as being the emergence of a more stable state as a result of the rearrangement of valance electrons. A more stable chemical state is one of a lower chemical energy, where chemical potential energy is the sum of the chemical potential energy and their kinetic energy. The electrostatic attraction between the electrons and the nuclei is the major source of chemical potential energy.

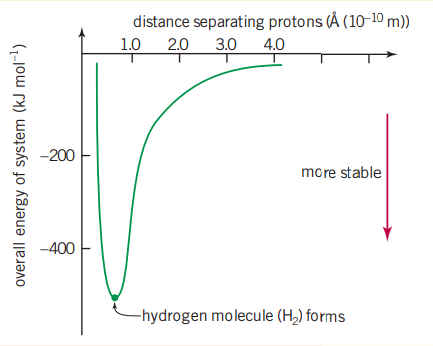

However as two or more atoms approach each other, they begin to repel, this is also true for their valance electrons. These repulsive forces also increase the chemical potential energy within the system. At a certain point, when oppositely charged ions are attracted to one another, the potential decreases. The ideal distance where the valance electrons are attracted to the nuclei but have the minimum repulsion by other electrons and the nuclei are have a similar relationship with other nuclei, is where the chemical potential is lowest and where the chemical bond forms.

The nature of the covalent bond:

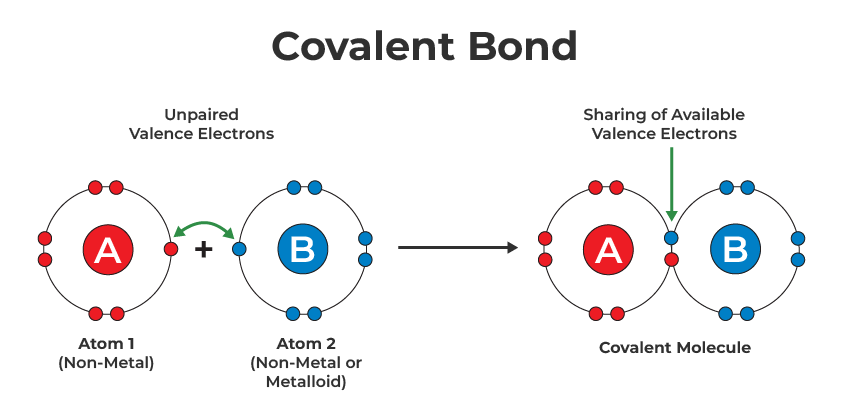

A molecule is a discrete group of non-metal atoms covalently bonded together; existing only in discrete ratios. There must be significant overlap of the atomic radii of two or more atoms to form a molecule.

Atomic radius relative to bond length

Arguably the simplest covalent bond is a diatomic molecule. An accurate measurement of the average molecules is now possible with modern X-ray crystallographic techniques (of which Dalton had no access to). The average radius of a hydrogen atom is but the atomic radius separating the two nuclei in a hydrogen bond is . This means that there must be significant overlap of the atomic radii of the individual atoms for a molecule to form.

As two atoms approach each other, electrostatic attractions and repulsions occur between the nuclei and the electrons. Where the greatest energy has been lost to the environment is where the bond forms. For hydrogen this happens at as where the lowest energy is, is where the atom is the most stable.

Covalent bond definition

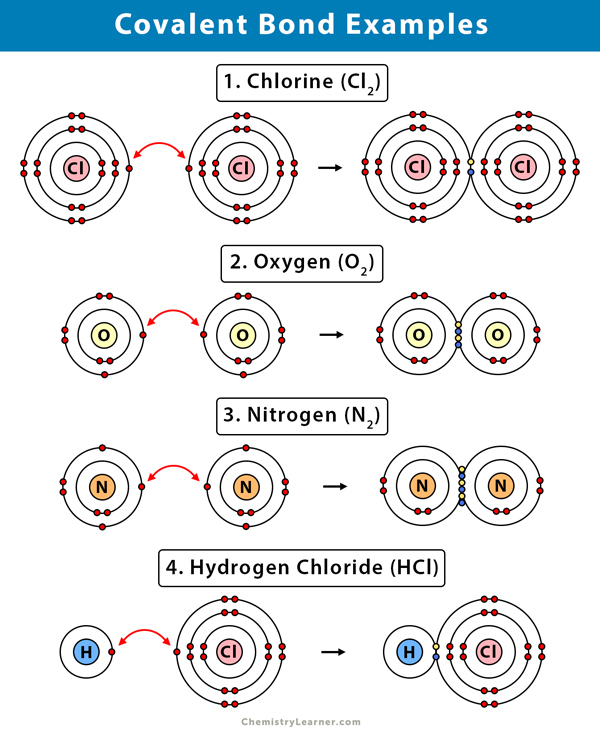

A covalent bond is formed when the valance electrons of a non-metal are rearranged and subsequently shared with one or more non-metals.

When covalent bonds form, they fill the octets of all elements involved.

Types of covalent bonds and electron arrangements

- Single bond (when 1 electron from each atom is shared)

- Double bond (when 2 electrons from each atom are shared)

- Triple bond (when 3 electrons from each atom are shared)

- Lone pair; non-bonding pair (when a pair of electrons exist only on one atom and don’t bond with another atom; and have significant implications for the properties of an element)

Formal Charges

Formal charges measure the “electron deficiency” of a certain atom in a covalent molecule. It assumes that each electron in a bond is shared equally by each bonding atom (e.g. fluorine pulls at electrons as hard as hydrogen in ). Where is the formal charge, is the number of lone pair electrons, and is the amount of bonded electrons (the reason only 1/2 is considered is because it has “1/2” of each electron in the bond=“sharing”).

Oxidation States

Given that oxygen has an oxidation state of -2 in all molecular substances (excluding peroxides), and hydrogen has an oxidation state of +1 in all molecular substances, (excluding hydrides), find the relative charge on an atom such that the net charge = the overall charge of the molecule.

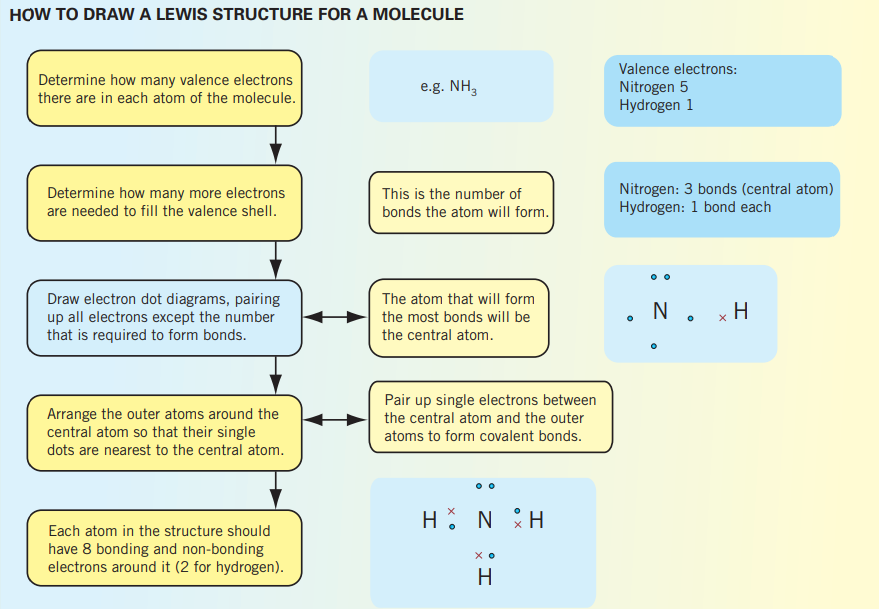

Lewis structures

Electron shell, Lewis, electron dot structures and diagrams, can be drawn to represented the electron configuration within an atom; representing its bonds and having all valance electrons represented. Bonds can be represented using dashes or two dots/crosses, where 1 dash is 2 electrons.

Diatomic molecules

Diatomic molecules are molecules composed of two of the same elements; examples include . The only non-metal elements that don’t form such bonds are elements in group 0/VIII as they already have a ‘full octet’ and are stable as is, phosphorus, sulphur as well as a few others.

The relationship between bond length and bond strength

A triple covalent bond between nitrogen atoms is very strong and explains why nitrogen is a relatively unreactive gas. It requires 945kJ/mol to break its bonds (for the sake of comparison, chlorine gas requires 242 kJ/mol). The amount of energy required to break a bond is the dissociation enthalpy for a substance, measured in kJ/mol. Additionally the bonding length of a triple nitrogen bond with itself, 109pm, is significantly shorter than that of a chlorine chlorine bond, 199pm.

(Bond length is the distance between two nuclei, when in its most stable state (has the least chemical energy))

VSEPR (Valance Shell Electron Pair Repulsion)

Lewis diagrams are useful for learning what a covalent bond is, but it has several flaws, the preferred way to represent a molecule’s arrangement and its structure is using its structural formula. Bonds are only represented using a line and their placement on the atoms matters. This is done to ensure that the diagram actually looks like the molecule depicted. Non-bonding electrons are represented the same as in Lewis dot diagrams.

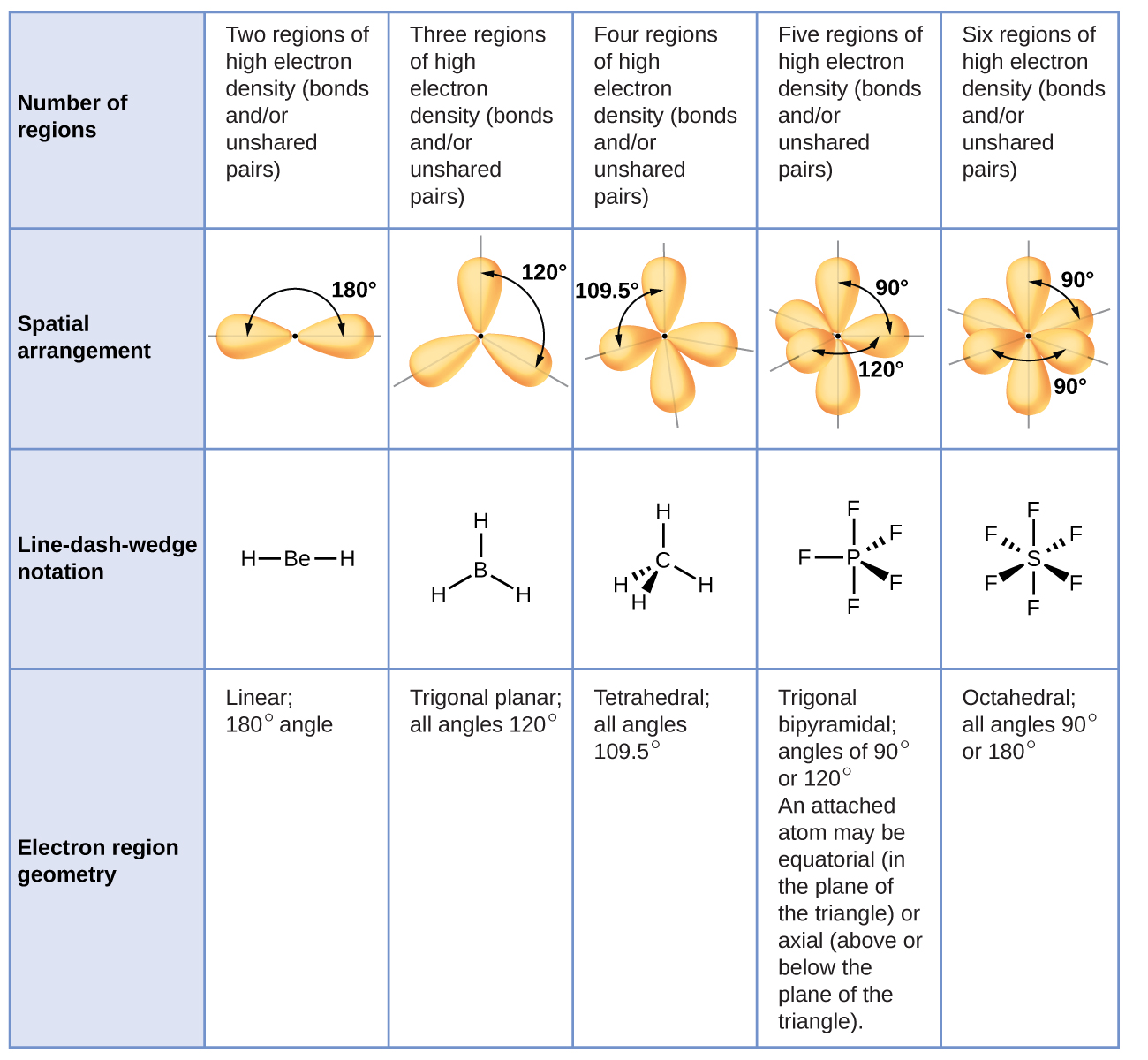

Due to electron repulsion, the electrostatic repulsion of pairs of electrons determine the geometry of the atoms in the molecule. The non-bonding pairs and bonding pairs of electrons are arranged around the central atom to minimize the repulsion of electrons. The relative magnitude of the strength of each kind of repulsion is: Non-bonding pair — non-bonding pair > bonding pair — non-bonding pair > bonding pair — bonding pair. When taking this into account, the bonding angle of atoms changes and is best seen when examining examples.

Transclude of vsepr-chart-table.avif

More on specific bonds:

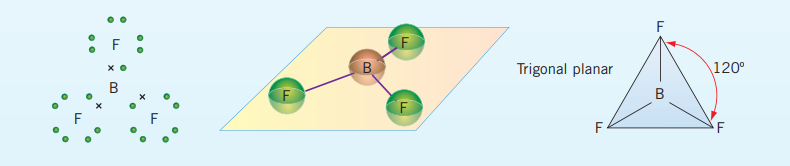

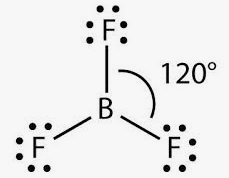

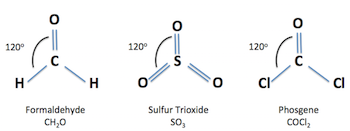

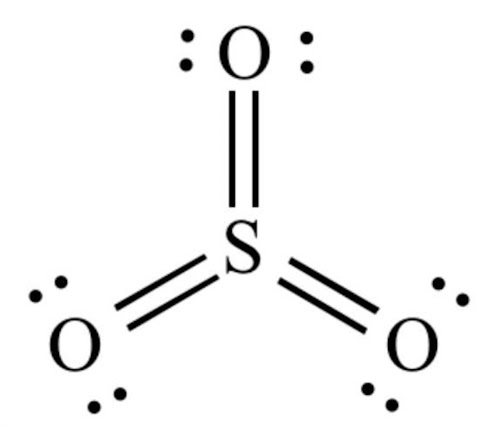

Trigonal planar bonds

These bonds form as a result of having a 3- charge on the central atom, bonding with three other atoms and the central atom having no lone pairs. Examples include: and takes the general form, .

In the unusual case of boron trifluoride to fill boron’s octet it only requires 6 electrons in its outermost shell.

Similarly in sulfur achieve a full octet with 3 double bonds (12 electrons in its outer ‘shell’) - the reason why both of these happen will be discussed in a later unit.

These have a bonding angle of

(Central atom can have multiple kinds of bonds as seen with )

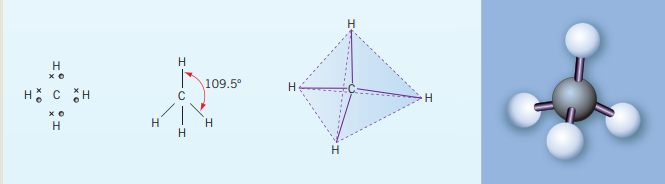

Tetrahedral bonds

These bonds are a result of the central atom having 4 bonding electrons, bonded to 4 atoms (often with a single bond) and no lone pairs on the central atom. Carbon is a common central atoms for these kinds of bonds.

An example of such a bond is methane, . As carbon is in group IV, it has 4 valance electrons; four bonding electrons. In order to minimize repulsion each bonded hydrogen is as far away from each other in a 3D space. This entails the bond angle for H-C-H bond to be

Bent liner (V-shaped) bonds

These bonds are a result of having two bonds with a central atom and two lone pairs of electrons. These molecules have the general formula of Examples include where both central atoms form single bonds with hydrogen. The resulting angle for the bond X-A-X is

V shaped bonds

Another version of the bent linear bonds are the V-shaped bonds. However they differ as the central atom only has one lone pair of electrons. They have two bonds and one pair of electrons. This results in V shaped bonds having a general formula of and a bonding angle of . An example of this is, .

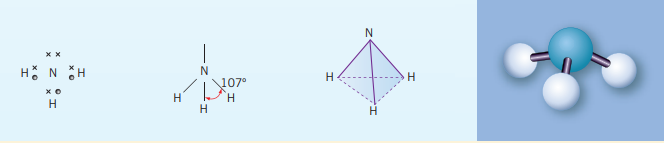

Trigonal Pyramidal

These bonds are a result of the central atoms having 3 bonding electrons and one lone pair. However, it does have a similar general formula to the trigonal planar, , but because there is a lone pair, the X-A-X bonds will have a bonding angle . For example, in an ammonia molecule, , nitrogen only needs to bond with three other atoms (single bonds) to have a complete octet. But due to nitrogen’s lone pair the bonds get ‘pushed down. The shape is similar to the tetrahedral shape but without a bond and at a slightly smaller angle. Another example of this kind of bond is .

Electronegativity and bond polarity:

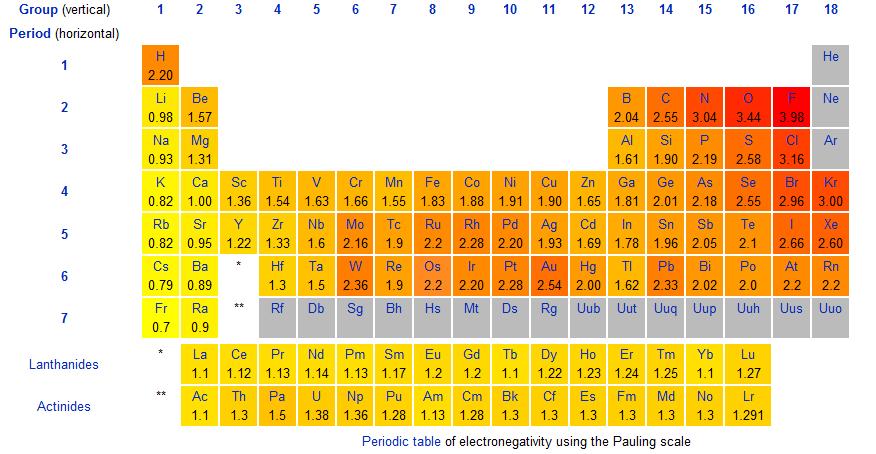

Electronegativity is a measure of the ability of an atom to attract the electrons in a bond. Electronegativity is the highest at the top left of the periodic table. As the valance shell of electrons is closest to the nucleus in smaller atoms. Elements that are closer to filling their shell are better at ‘taking away’ electrons to become stable. The most electronegative element is fluorine. (Group 0 (VII) have already completed filling their valance shells and have an undefined electronegativity)

Comparisons between electronegativity values can be used to make generalizations about the type of bonding and types of atoms forming a bond. Elements such as fluorine and oxygen have higher electronegativities. The difference in electronegativity is the strength at which the element with a higher electronegativity pulls the electron that is shared in a bond. For diatomic molecules or bonds that are of equal strength, the difference in the atoms’ electronegativity is 0.

Pure covalent, polar and ionic bonds in terms of electronegativity

- Difference less than 0.5: This difference will form pure covalent bond, non-polar bonds.

- Differences between 0.5 and 1.8: This difference of electronegativity results in a poler bond; a covalent bond that has a positive end and a negative end.

- Differences of 1.8 or more: This is an extreme difference in electronegativity which most likely results in ionic bonds being formed, where the difference is high enough for an electron to be taken away entirely. **There are a few bonds that defy the boundaries of what is considered ionic and covalent, but the difference in electronegativity is used as a general outline to identify the bonding types of compounds.

Polar bonds and molecules

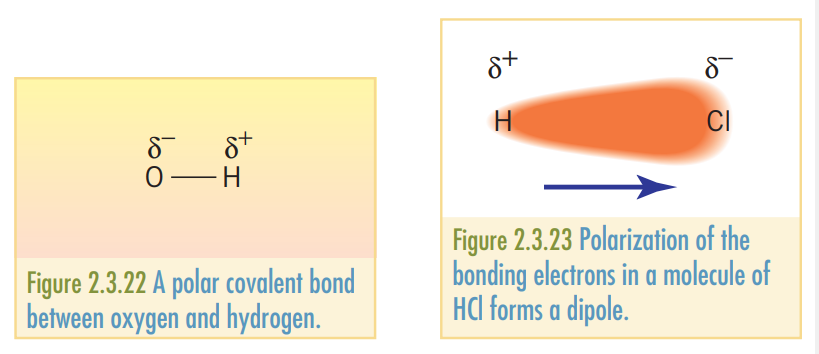

If the electrons are shared unevenly in a covalent bond, the bond is said to be a covalent bond or a permanent dipole. Such a bond can be identified using, . Where and are used to represent positive and negative dipoles respectively.

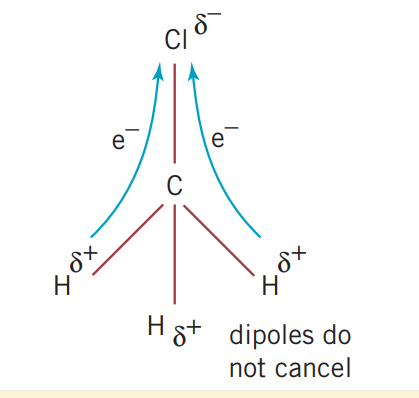

In cases where the net polarized electronegativity of the dipole has a direction, the molecule is said to be a polar molecule as there is an overall electronegativity towards one region of the atom. For instance, in the bond, , the polarity is towards the atom.

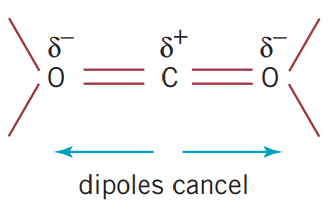

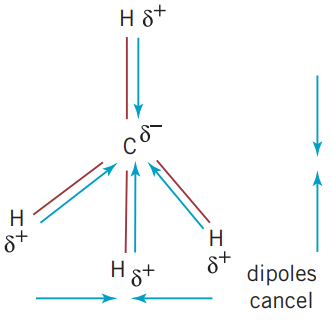

However, just because a molecule has polar bonds, it is possible for all the dipoles to cancel each other out. An example of this is in methane, . As all of the bonds all have the same difference in electronegativity. When determining whether a molecule is polar, the shape of the molecule must be considered. Due to methane’s tetrahedral molecular structure, all of the dipoles cancel each other out.

However, in the case of chloromethane, , there is a significantly larger pull towards the atom. It has a similar molecular structure to methane, however, due to the difference of electronegativity in the bond, being grater than that of , the overall polarity is towards the atom.

2.4 Covalent bonding and network lattices

Several elements exist in different structural forms. For instance carbon, exists as diamond, graphite and fullerene, . Different structural forms are allotropes.

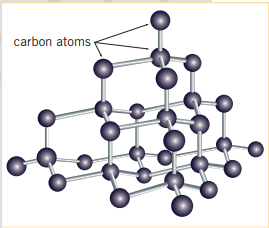

Diamond

Diamonds are hard, non-conductive, clear solids that are used to cut hard materials (including other diamonds), and as jewelry (very unpleasant history + not relevant) The structure of a diamond is a result of carbon bonding with other carbon atoms in a tetrahedral fashion. All four of a given carbon’s valance electrons are used to bond with other carbon atoms. This is a contributing reason why diamond is non-conductive (electricity). Because the bonding forces within diamonds are strong, it is a hard substance (having a Moh of 10) and the energy required to break these bonds and turn diamond into a gas (sublime the substance), diamond must be at .

In order to cut a diamond, the cleavage plane, must be found; it is found at a specific angle as to cleave the diamond and not shatter the diamond (similar to a domino effect)

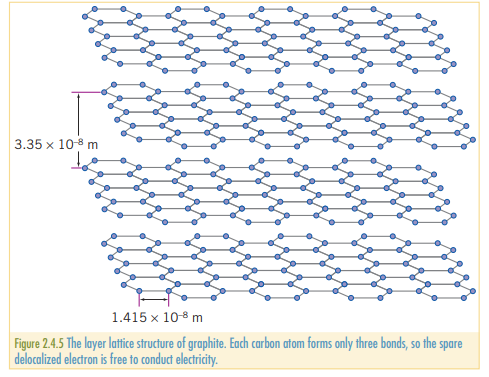

Graphite

Graphite is a soft, greasy solid that is a good conductor of electricity. Common applications include, pencil ‘lead’, inert electrode in dry cells, and parts of a composite material used in the strings of tennis roquettes. It is also used as a moderator in nuclear reactions, used in mechanics and sports.

In the giant covalent structure of graphite, a given carbon atom is bonded to 3 other carbon atoms, leaving one unattached electron, in between the layers of graphite.

The delocalized electron is free to move around, and is the reason why graphite is conductive (and explains why diamond is not.) With only the weak Van der Waals forces keeping the layers of carbon together, it is easy for layers to slide on top of each other. Because the bonding within the layers is strong, it similarly has a high melting point of .

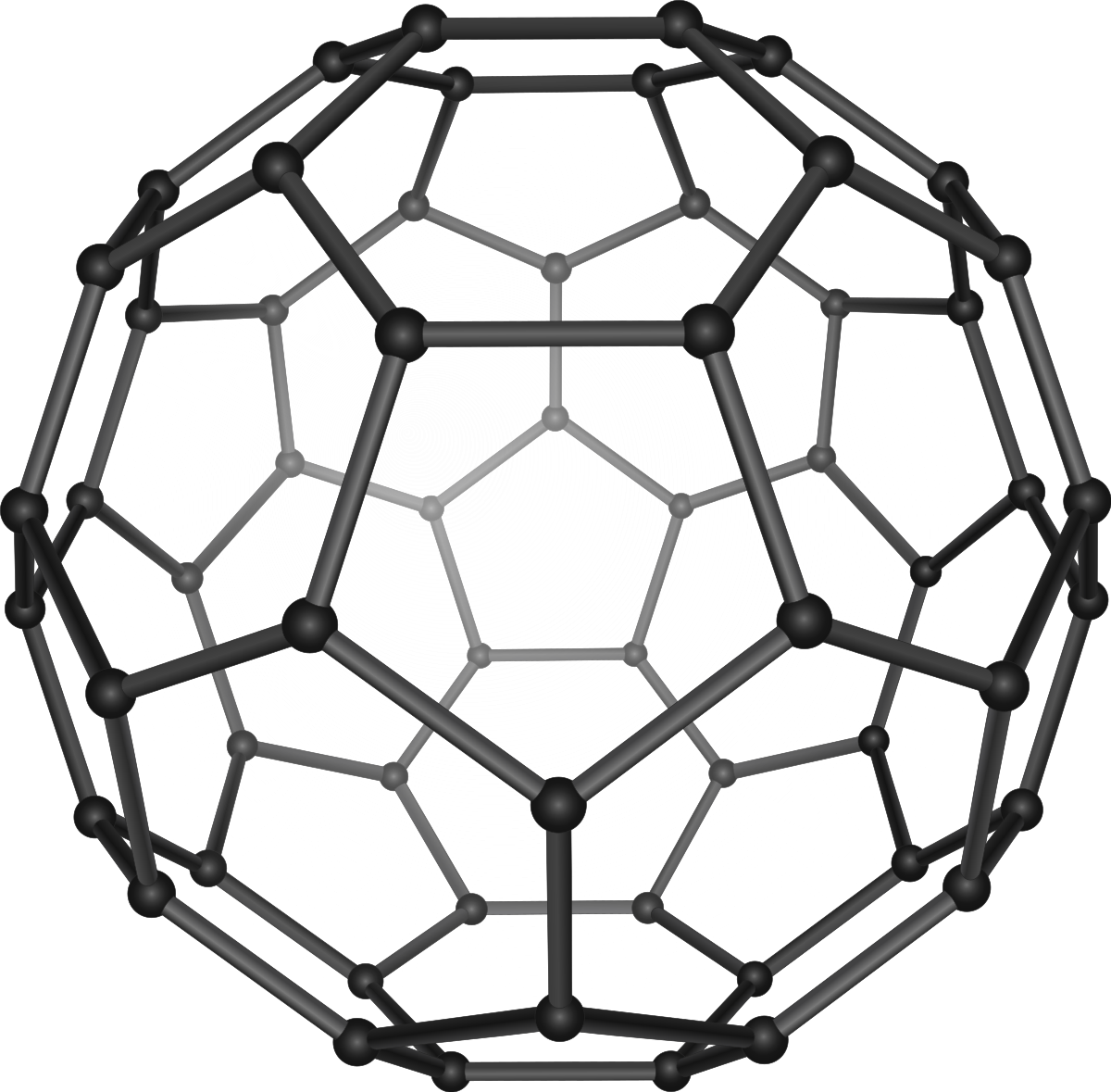

Fullerenes (buckyballs)

There is one free electron per carbon atom in this molecule. Allowing these molecules to conduct electricity, are superconductive, used int the production of micro-scale semiconductors, used in electrochemical devices and broad-spectrum lasers.

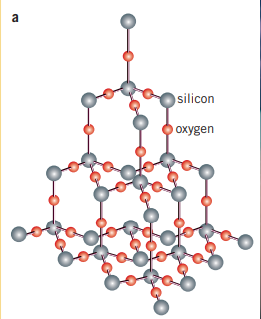

Silicon and silicon dioxide

Similar to carbon, silicon is a group 4 element, which allows it to create a tetrahedral lattice network, similar to diamond. Silicon crystals are dark blue-grey and is well known for its ability to bond with and become a semiconductor. As has a bonding length of 235.2pm, ( bonds have a bond length of 142.6pm), the bond strength is less and consequently has a lower melting point than that of diamond

Silicon dioxide, or silica, is a major part of sand, and is used to make glass. It is a network covalent structure made up of 1 for every 2 . Silica is found in sandstone, silica sand, and quartzite. In its crystal form, it is known as quartz.

2.5 Intermolecular forces

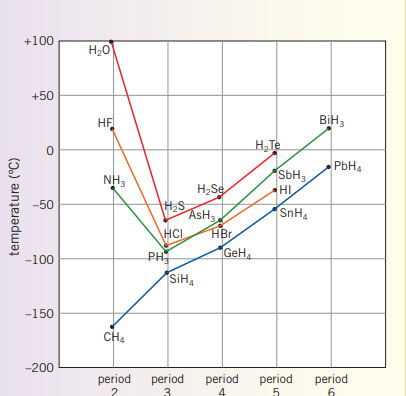

When water boils, water molecules are not breaking ( bonds), rather they are separating themselves to become gaseous. The bonds that are being broken are the intermolecular forces that bond one water molecule to another. The strength of the intermolecular forces determine a substance’s melting and boiling point. The strength of intermolecular forces are determined by the strength of he electrostatic attraction between molecules, which depend on if the molecules are polar or non-polar, big or small.

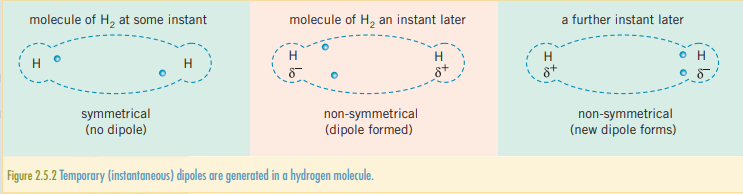

Van der Wall’s forces (London dispersion forces)

As not all substances are polar, and said substances exist at room temperature as solids and liquids, some force must be keeping them together. They are being kept together by the London dispersion force, LDF.

Considering the orientation of electrons, both bonding and non-bonding, it is possible for several electrons to be in a region. This results in an instantaneous dipole, which causes one region of a molecule to be more negative than another. Once an instantaneous dipole has been generated, it will influence the electrons on other molecules close to it, cascading across the substance. A moment later the molecule will have a different orientation but averaging out to have no permanent dipole. The billions of temporary dipoles will have resulted in a weak overall attractive, van der Waals’ force or LDF. They exist in all molecules.

The larger a molecules, the greater amount of electrons there are to produce an instantaneous dipole. The more electrons there are, the more pronounced an instantaneous dipole can become in an atom. The more pronounced an instantaneous dipole can become, the stronger the LDF forces and the higher the melting and boiling point will be.

| Molecule | Number of electrons in molecule | Melting point (C) | Boiling point (C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorine, F2 | 18 | -220 | -188 |

| Chlorine Cl2 | 34 | -101 | -35 |

| Bromine Br2 | 70 | -7 | 58 |

| Iodine I2 | 106 | 114 | 184 |

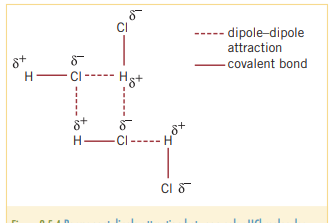

Permanent dipole attraction (dipole dipole attraction)

Polar molecules have a permanent dipole, where one ‘end’ of the molecule is always more positive than another end. For example, is a polar molecule where is the more negative side and is the more positive side. This results in in different molecule being attracted to in the aforementioned molecule.

Based on polarities alone, it would be reasonable to assume that would have a greater boiling/melting point than for instance. However the number of electrons is significant as has twice as many electrons as , the temperature required to melt/boil a substance.

**The reason why has a greater boiling point than any of the other hydrogen halides in the table is because is has hydrogen bonding

| Hydrogen Halide | Melting point (C) | Boiling point (C) |

|---|---|---|

| HF | -83 | 20 |

| HCl | -114 | -85 |

| HBr | -87 | -67 |

| HI | -51 | -35 |

Hydrogen bonding

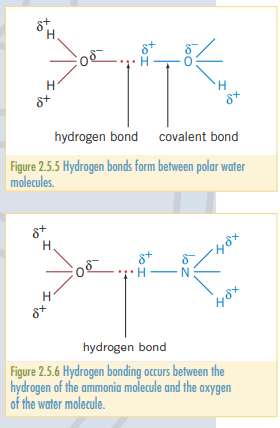

As elements like all have large electronegativities, when bonded with hydrogen, they forma particularly strong polar bond. This is a special case of dipole-dipole bonding.

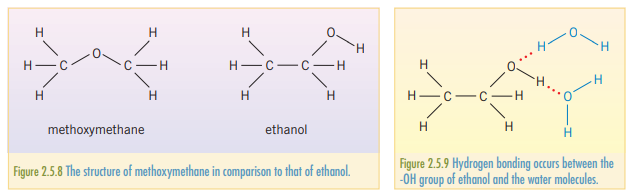

For instance, water exhibits hydrogen bonding and has a relatively high melting and boiling point when compared to other covalent molecules. Additionally, water has a low density when froze, and high surface tension (think belly flop) can be explained through hydrogen bonding.

Ammonia, , similarly to water, has a relatively high boiling and melting point