2024-07-1015:25 Status:IBnotes

Introduction to Chemical Equilibrium

Up to this point in chemistry, we assumed that reactions always proceed from reactant to product, however, this is not true in all reactions. For example when we react :

- All four chemicals can be detected after the reaction is complete.

- The collision between produces the product.

- The collision between produces the reactants.

The forward reaction is the reaction where the reactants create the products. (reactant → product) The reverse reaction is the reaction where the products create the reactants. (product → reactant) An equilibrium reaction is a balance between the forward and backward reactions. This is denoted by using the equilibrium arrows, . The reaction mentioned earlier, would written more accurately as:

Conditions of Equilibrium

- The reaction must be a closed system. (If there were other influences, the system would be compromised - see ozone.)

- No macroscopic or observable changes

- The equilibrium is considered to be dynamic, that is the reactions have not actually stopped but the rate of the forward and reverse reactions are the same

Initially, the majority of the reactants will form the products but gradually the reverse reactions will start to balance out the forward reaction (Think of this like a game of dodgeball where one side has all the balls at the beginning.)

Three kinds of equilibrium

- Chemical reaction equilibrium

- Solubility equilibrium

- Phase equilibrium

Percent reaction at chemical equilibrium

The amount of product produced vs. the theoretical maximum yield is what defines the percent reaction. This is away to express the position of equilibrium.

- Reactions that proceed more than 99% are: quantitative

- Complete reactions, (AKA: quantitative reactions and stochiometric reactions)

- The reverse reaction is more or less negligible

- Often use ‘→’ arrows

- An example of such a reaction is a combustion reaction

- e.g.

- Reactions that proceed between 99% and 50% are product favored reactions.

- These reactions are common for weak acid/base reactions.

- These reactions are common for weak acid/base reactions.

- Reactions that proceed above 1% but less than 50% are reactant favored reactions.

- These reactions are common for weak acid/base reactions.

- These reactions are common for weak acid/base reactions.

- Reactions that proceed at 1% or less are non-spontaneous reactions.

- No observable product is formed.

- Requires constant support from external forces to be sustained.

-

** The would not be detected.

-

Calculating and Using %Reaction

Calculating percent reaction, is very similar to calculating percent yield.

For example, weak acids do not ionize at 100%. They only produce a small percentage of the expected hydronium ion.

- If there is 3.00 mol/L of solution produced 0.60mol/L of solution, what is the percent reaction? Is this product or reactant forward?

It is expected that if there are 3.00mol/L of solution, there should be 3.00mol/L of solution. As per their balanced equation: .

If there was only 0.60mol/L of solution, then the percent reaction would be: . Thus the reaction would be reactant favored. 2. If the percent reaction would be 38%, what is the concentration of ? ; Leaving 62% of the reactant unused 1.86 mol/L of reactant remaining.

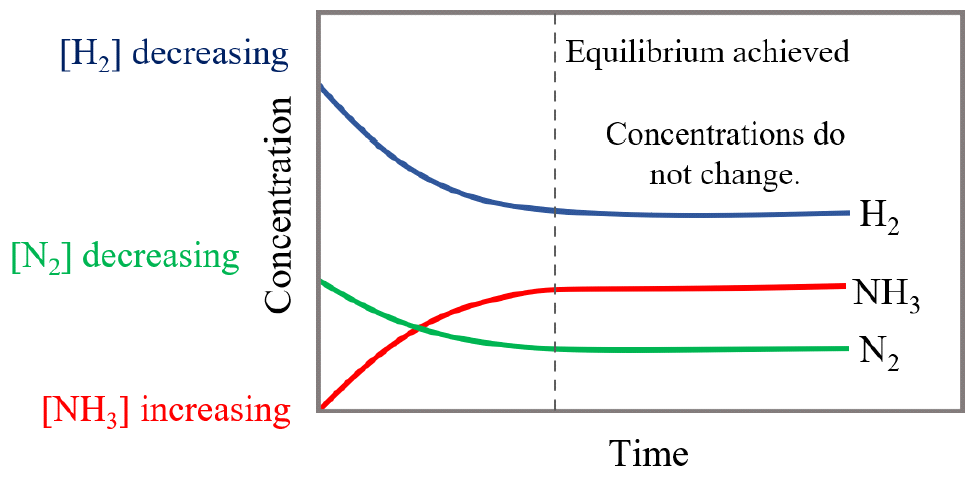

Concentration Curves

ICE (Initial-Change-Equilibrium) Tables

ICE tables can be used to track all information regarding equilibrium.

- Set up the ICE table with a column for each compound in the reaction. However, this is a concentration table therefore, we only include gases and aqueous solutions - ignore solids and liquids.

- Set up three rows for ICE.

- Fill in with all given information and also ensure that the initial concentration of the product is 0

- Complete the table

- Enter the concentration of each substance and their changes.

- We can use the molar ratio to calculate the change for all the other columns.

- Concentrations change reverse signs when calculating between reactants and products.

- Use “X” to indicate an unknown change.

Quantitative Changes in Equilibrium

It is possible to solve equilibrium concentration using the following formula:

\begin{gather} K_{c/eq} = \frac {[C]^c[D]^d}{[A]^a[B^b]} \\ (aA + bB \rightleftharpoons cC +dD) \end{gather}

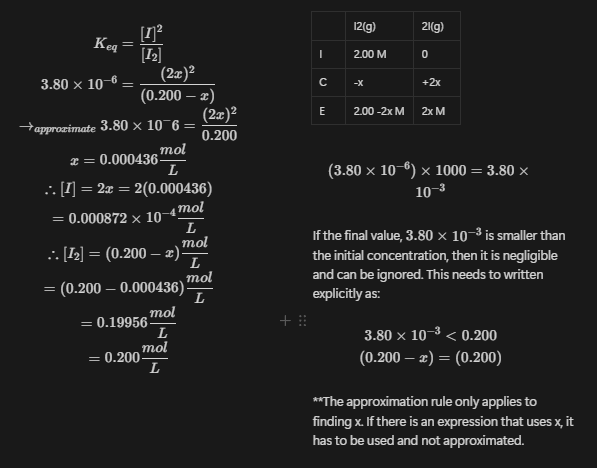

When solving for the concentration of (an) unknown value(s), when given can be solved for algebraically.

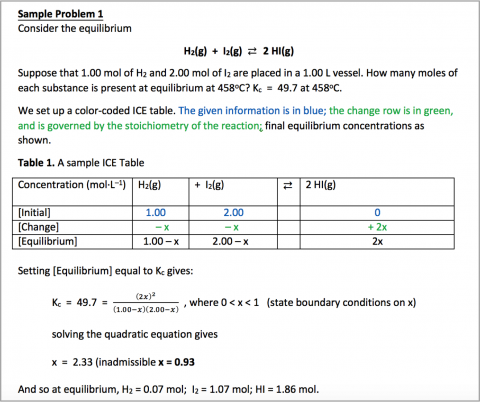

Example 1:

For the following reaction, , determine the concentration of , and at equilibrium.

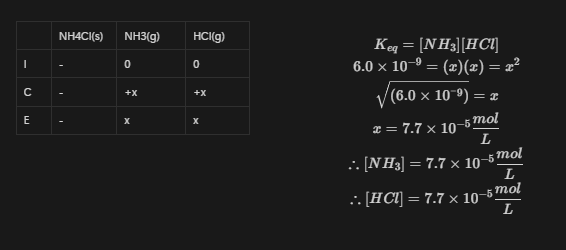

Example 2

For the following equilibrium reaction, , where the initial concentration of , determine the concentrations of all the substances involved.

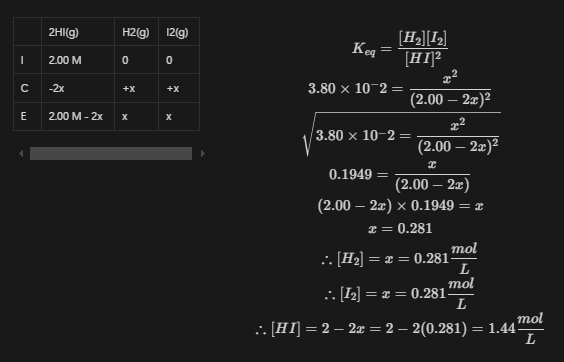

Approximation Rule:

If the initial concentration is greater than , then we can ignore the change that is happening to the initial concentration. This CANNOT be graphed when solving problems (for reasons :)) The application of this can be seen in the following example.

Example 3

At 72 for the reaction is . If the original concentration for , calculate the equilibrium concentrations.

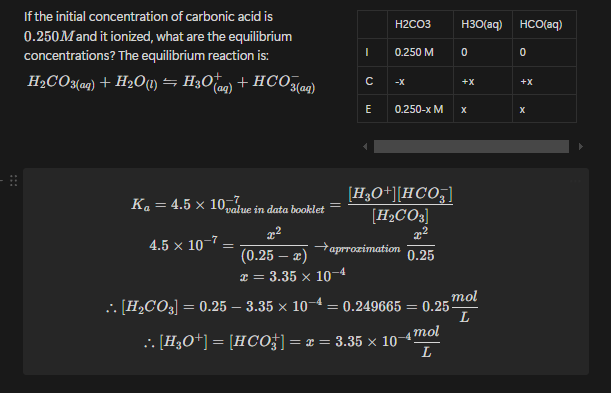

Example 4

If the initial concentration of carbonic acid is and it ionized, what are the equilibrium concentrations? The equilibrium reaction is:

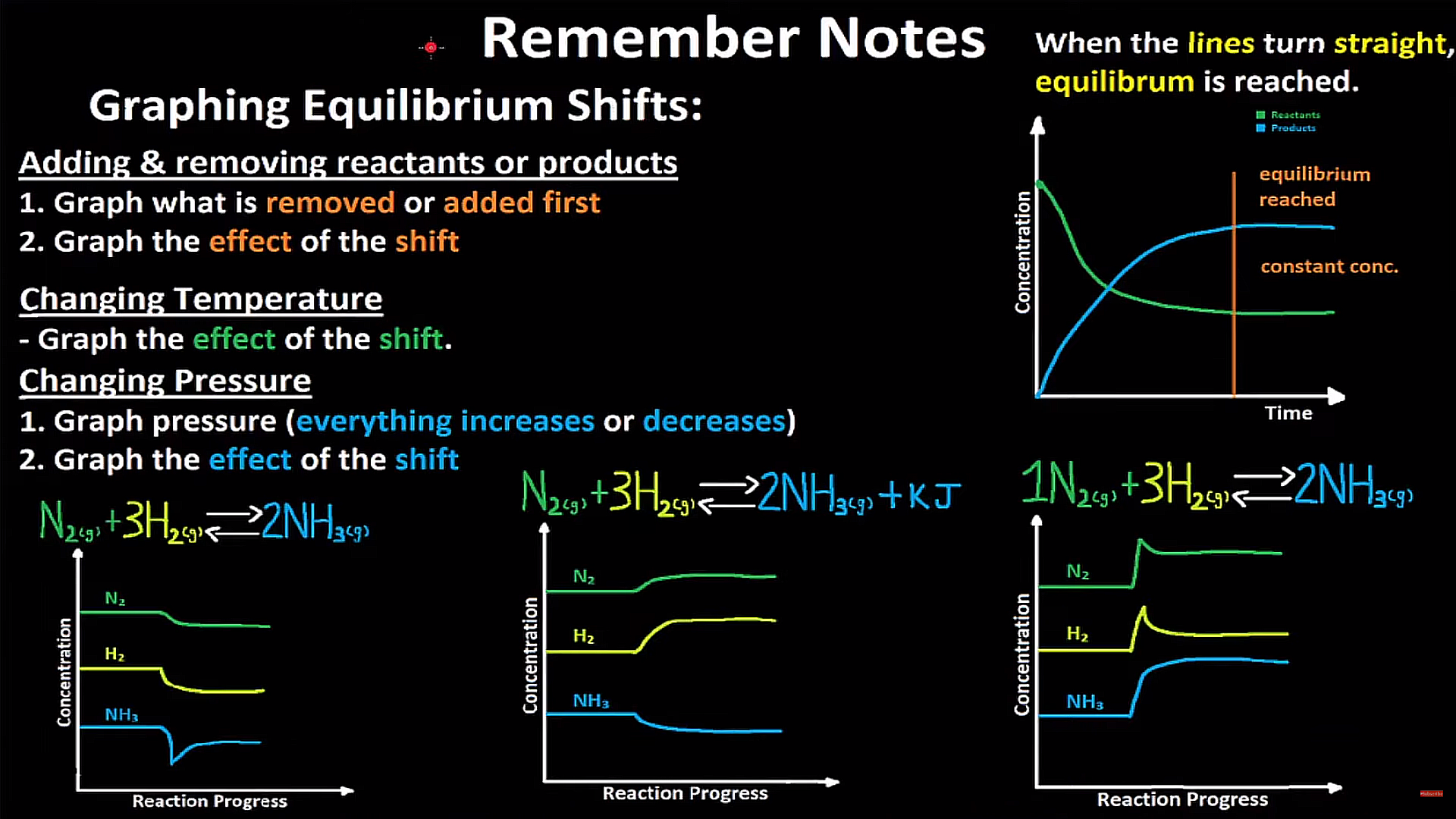

Le Chatelier

Several reactions is a closed system will reach equilibrium and if nothing is done to the equilibrium, it will stay that way. Le Chatilier’s principle states that when an equilibrium is disturbed (or experiences a stress), the system will adjust in a way that opposes that stress, and reach a new equilibrium. That is to say that when some ‘stress’ is put upon a system, it will naturally try to balance itself out. The major means of stressing an equilibrium system are as follows:

Concentration change

- If a reactant is added, the equilibrium will shift right/shift forward. This happens because there is ‘too much reactant’ and the system will tend to make more product to compensate for the relative lack of product. This is also true when product is removed as relative to the amount of product, there is a deficiency.

- Similarly, if a product is added, the equilibrium will shift left/shit backwards. This happens because there is ‘too much product’ and the system will tend to make more reactant to compensate for the relative lack of reactant. This is also true when reactant is removed as relative to the amount of product, there is a deficiency.

This can be seen when the concentration of is increased (reactant) and the reaction shifts left. Immediately after is added, the concentration decreases along with whereas the concentration of increases.

Note that the remains the same.

Temperature change

When dealing with a change in temperature, first identify whether or not the reaction is endothermic or exothermic. Appropriately assign energy as a term in the reaction and consider a change in temperature a change in the concentration of energy.

- For an exothermic reaction: . If the decreases, the equilibrium shifts left.

- For an endothermic reaction: . If the increases, the equilibrium shifts right.

Note that the only stress that can change the equilibrium constant of a system is a change in temperature.

Gas volume change (pressure change)

The concentration of the gas is directly related to the presume of the gas. As volume and pressure are inversely proportional.

- An increase in volume results in a decrease in pressure, thus decreasing the concentration.

- A decrease in volume results in an increase in pressure, thus increasing the concentration. If volume is altered in any way, the most effected portion of the reaction (either product or reactants) is the ‘side’ with the most moles of substance. This can be rationalized as the higher concentration would effect the reaction that has more ‘opportunity’ to collide and react.

For example: Suppose that the volume of a container decreases (pressure increases), will the reaction shift left, right or remain at the same equilibrium? As the products have 2 mols, a relatively smaller quantity than that of the reactants’ 3mols of substance, the equilibrium would shift right.

Catalysts and inert gases

Adding inert gases (substances that do not interfere with the reaction) and catalysts (substances that ONLY speed up the rate at which a reaction occurs) both do not partake in the equilibrium reaction. Thus, neither are stressors.

Summary and Graphs

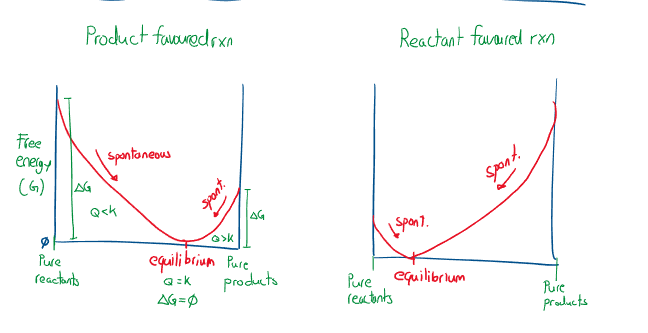

Q and Gibbs Free Energy

is the reaction coefficient/quotient, not to be confused with = Heat. It has the same formula as but where is a record of the equilibrium after it has been reached, is a measure of the equilibrium at an instance of time prior to equilibrium. In general helps find where the equilibrium reaction is.

- - equilibrium has been reached

- - equilibrium has not been reached, and it is experiencing a forward progression

- - not at equilibrium, and there is too much product. And there is a reverse progress

Gibbs free energy

Recall that means that a reaction is spontaneous. (There is free energy available to break bonds, and partake in reaction). When Gibbs free energy = 0, the reaction is at equilibrium. Consider a reaction that only has reactants: The reaction will be driven forward (spontaneous reaction). Eventually which is another way of communicating that the spontaneity of the forward reaction is the same as the spontaneity of the reverse reaction. Additionally equilibrium occurs when there is maximum entropy possible in a system and minimum free energy. This can also be expressed graphically:

Where the greater the absolute Gibbs free energy of a system in equilibrium the further away it is away from equilibrium, and more spontaneous the reaction will be. Where the closer the reaction is towards having pure reactants, , the more forward favoured the reaction will be, and vice versa. For a qualitative reaction, to reach equilibrium, there must be a near complete forward reaction.

Finding the Gibbs free energy using of an equilibrium system:

Where is the Gibbs free energy in , is the universal gas constant = 8.314 \frac {J}{mol\times K}$$T is the temperature in , and is the equilibrium constant (unitless).

Example 1

The formation of at has Calculate the equilibrium concentration of ammonia if the and at equilibrium \begin{gather} N_2 + 3H_2 \rightleftharpoons 2NH_3 \\ \Delta G ^ {\Theta} = -RTln(K_c)\\ ln(K_c) = \frac {\Delta G^{\Theta}}{-RT} \\ ln(K_c) = \frac {(-33.32) \frac {kJ}{mol} \times \frac {1000J}{1kJ}}{-(8.314 \frac {J}{mol \times K})(300K)} \\ln(K_c) = 13.3654... \\ K_c = e^{13.36554 } = 637562... \\ K_c = \frac {[NH_3]^2}{[N_2][H_2]^3}\\ 637572... = \frac {[NH_3]^2}{(0.2)(0.1)^3} \\ \therefore [NH_3] = 11.3 \frac {mol} L \end{gather}

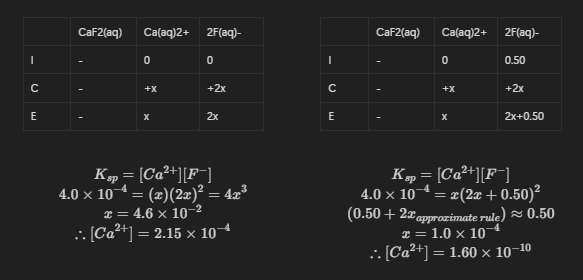

Solubility equilibrium:

Ionic compounds and its dissociation in water:

- If an ionic compound has a high solubility, it can be expressed as a qualitative reaction. For instance: .

- If an ionic compound has a low solubility, it can be expressed as an equilibrium reaction. For instance: Before the equilibrium reaction occurs, the solubility of the reactants (solid) would not be a part of the reaction. Thus, the conventional equation cannot be used as there is no value for the denominator: . Thus, the formula: is used to determine equilibrium. For the aforementioned low solubility ionic compound would have an equilibrium constant of: .

Note that molar solubility - what is the concentration at equilibrium.

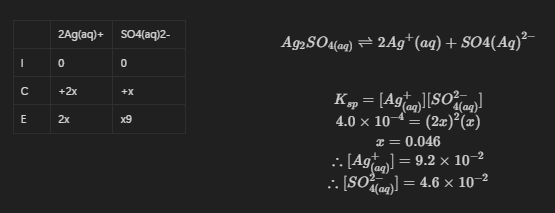

Example 2:

Silver nitrate has a . What concentration of ions are expected in solution?

Example 3:

If of is mixed with of will a precipitate form?

Therefore, no precipitate is formed as precipitate only forms when

Common ion effect

When two solutions are mixed with a common ion, it impacts the solubility of each other.

Example 4:

Given , what is the molar solubility of without any other ions and with the initial concentration of ?

Comparing the concentrations of ion when there is an initial concentration of fluorine is above 0, the consequence is that the Calcium will not dissociate as well.

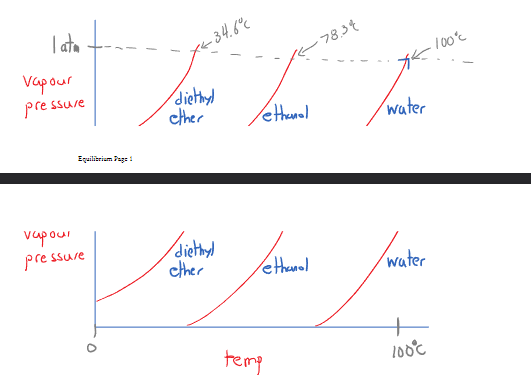

Phase change equilibrium

To demonstrate phase equilibrium the following example is typically used: Normally when we place a cup of water out, the water will evaporate. This occurs because some of the particles have significantly more kinetic energy that the average amount. (For more on this, see normal distribution and Maxwell-Boltzmann curve).

- Some particles have sufficient energy to vaporize. (Enough energy to overcome intermolecular forces that keep the liquid ‘together.’

- In a closed system, the vaporized particles can also cool off and recondense into a liquid.

The aforementioned water example can experience a phase change equilibrium, represented as:

Where the rate of vaporization and condensation are equal. Note that the equilibrium can be shifted only by changing the heat, concentration and pressure of the system.

Vapor change

Vapor pressure is the pressure from the vapors formed at equilibrium. The vapor is pushed against atmospheric pressure and thus pressure can be changed based on the temperature and the strength of the intermolecular forces.

A liquid boils when where the pressure of the vapor overcomes the pressure imposed by the atmosphere. However a liquid also starts to boil when where the vapor is crushed back into a liquid. Additionally the boiling point decreases at lower atmospheric pressures.

The graph to the right communicates that a phase change may occur due to an increase in temperature or an increase in pressure.

Contact and Haber Process

Contact process is the process for manufacturing sulfuric acid. It is called contact process because of the stage where sulfur (IV) oxide and oxygen come into contact with a catalyst. This process occurs across 3 stages:

- Sulfur is burned to make sulfur (IV) oxide:

- Sulfur dioxide is then mixed with more oxygen and passed over a vanadium (V) oxide catalyst at -, producing sulfur (VI) oxide.

- The sulfur (VI) oxide is then cooled and absorbed into a sulfuric acid and water solution, making it into a pure acid. This reaction is exothermic, as adding too much sulfur (VI) oxide would cause the acid to vaporize

The equilibrium for this reaction is: .

Haber process

The Haber process is the process used to manufacture ammonia gas. The equilibrium reaction is: .

- The activation energy for this reaction is large and reactant favored.

- It recycles unused gases and is rapidly cooled to remove ammonia.

- This is performed at extreme pressures and at moderate heat.

- This process yields approximately 20%.

- Effect of pressure (- ).

- The equilibrium favors the product’s formation.

- Temperature must be at least

- even though this process is exothermic, or so is required to break nitrogen under normal conditions.

- Removal of liquified ammonia.

- By removing the product and cooling it and the turning it into a liquid, the process can continue to be a forward reaction.

- Recycling of the reactants back into the reaction chamber creates more product.

- This process is speed up by an iron catalyst

- Has no effect on the equilibrium.

- Only makes the reaction faster.

- This is not a pure catalyst (iron oxide).