2024-07-1113:49 Status:IBnotes

Addition reactions

Addition reactions are reactions wherein alkenes and alkynes have their double bonds broken and new elements are added. There are a few variations of this.

Hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is the process of adding to an alkene: e.g. The general reaction for this is: .

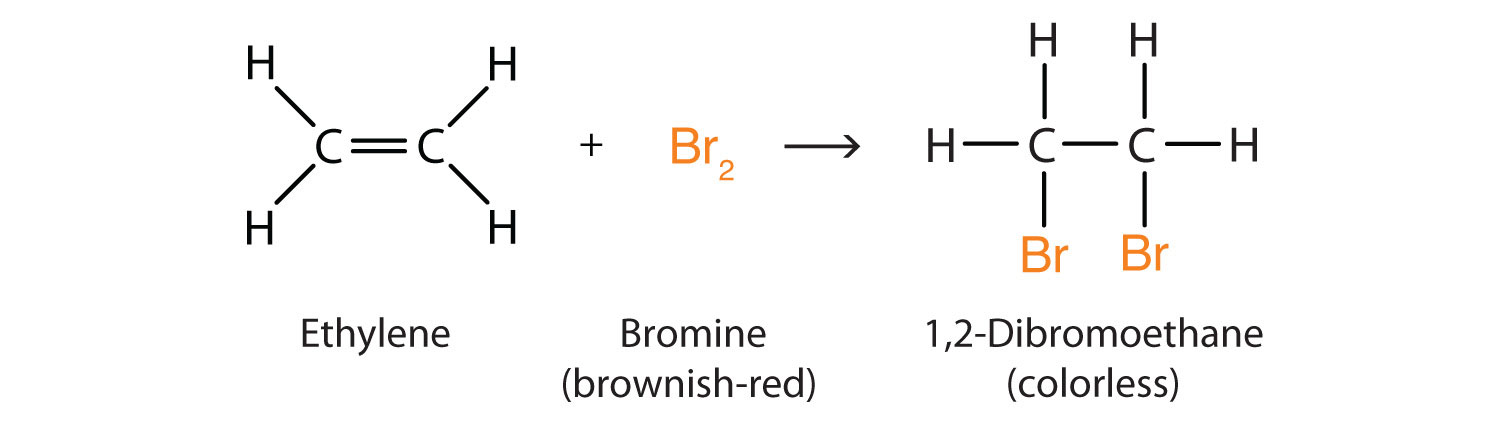

Halogenation

Halogenation is the process of adding to create an alkyl halide The general reaction for this is: .

This is the process for which alkyne and alkene detection works: With alkynes, this process occurs twice

Combustion

Complete

In a complete combustion, there is a rich amount of oxygen; thereby creating and (If the system is closed, then there is water vapor, if the system is closed then liquid water is produced.)

Incomplete

In an incomplete reaction there is a deficiency in oxygen, creating . Where is soot/coke/a pure form of carbon.

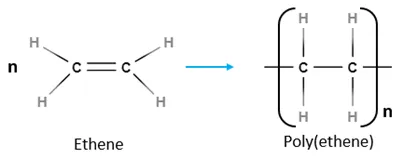

Polymers

Polymerization is the formation of very large molecules from many small units, monomers. Wherein a monomer is a single ‘unit,’ dimer is composed of two units, trimer is composed of three units, and polymers are composed of several units.

Polymers can have a variety of unique physical and chemical properties. Examples include: (Synthetic) plastic, nylon and Kevlar; (natural) proteins (amino acids), carbohydrates (starch, cellulose, etc.), DNA, spider thread.

Addition polymers

Addition polymers are a result of linking alkenes through addition polymerization. The double bond is broken; allowing for carbon to have two more free bonds. When this occurs on a large scale, the free bonds of one alkene bond with another; creating long strands of polymers.

Condensation polymers

Condensation polymers are always result in the polymer and a small extra molecule, . Esterification is a type of condensation reaction. Catalysts for his reaction are and heat.

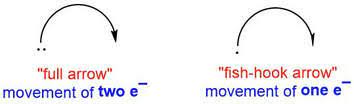

Important Symbols (Curly Arrows)

A ‘full’ movement is equivalent to 2 electrons moving, and is signified with an arrow with ‘hooks’ (curly arrow) on both ends. A ‘half’ movement is equivalent to 1 electron moving, and is signified with a ‘hooked’ (fish-hook) arrow

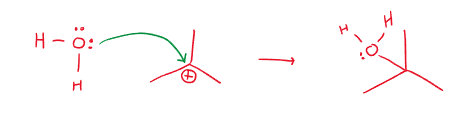

3 Electron movement scenarios

- A lone pair of electrons moving towards electrons in a bond: E.g. The lone pair of electrons on an oxygen atom moving to the positive part of a degree 3 carbon, forming a coordinate covalent bond.

- A pair of electrons in a bond going towards a lone pair of electrons: E.g. A \sigma bond moving towards the lone pair of electrons of a chlorine atom. - Forcing the two to separate.

- A pair of electrons in a bond moving to another bond. E.g. The electrons in a double bond moving to some hydro-halide; forming a single bond with a hydrogen, forming a chlorine ion, and having it bond to the now positive, formerly double bonded carbon.

- A lone pair to lone pair does not occur.

Bond cleavage

Heterolytic fission

Heterolytic fission is where both electrons in the bond go to either or (based on typical ionic charges), to form and (or and ).

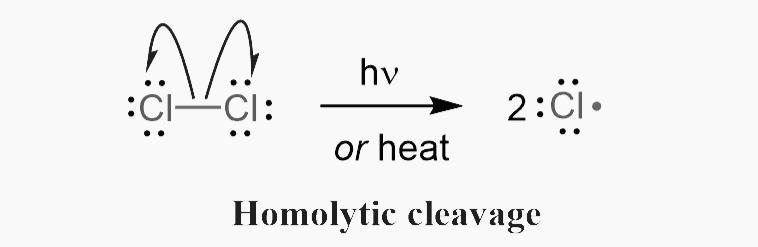

Homolytic fission

Homolytic fission is where one electron goes to both species and . and then become highly reactive radicals. E.g. .

Free Radical Substitution

Free radical substitution can be seen in reactions such as halogenation and substitutions of alkanes:

Step 1 - Initiation:

Heat or UV light causes the weaker bonds in the halogen to undergo homolytic fission. Two radicals are produced.

Step 2.i - Propagation:

The halogen radical abstracts (steals) a hydrogen to form and an alkyl radical (methyl radical).

Step 2.ii:

The alkyl radical will abstract a chlorine atom to form the product and a new chlorine radical continuing the cycle. The other chlorine radical can then participate in 2.i.

Step 3 - Termination:

Various reactions between radicals allow for the formation of the final products and ends the radical cycle by ‘removing’ radicals from the system/cycle.

- FRCR - Free Radical Chain Substitution.

Termination also forms: Organic mechanisms and reactions

Nucleophilic Substitution

Nucleophilic substitution occurs through one of two mechanisms: and . The mechanism is dependent on structures of the reactants, the solvent. Where stands for substitution, stands for nucleophilic, is for unimolecular, and is for bimolecular.

A nucleophilic substitution involves:

- A nucleophile, a nucleus seeking molecule

- A substrate (electrophile), a molecule that is being reacted with (must have a polar bond * The carbon must be have a slightly positive dipole, ).

- A leaving group - the material that is being substituted (in general, the more polar this is, the better it acts a leaving group).

Nucleophiles

- Larger elements are stronger nucleophiles than smaller elements, since they have less attraction to their electrons (this relates to the atomic distance and shielding of electrons).

- The more electronegative the nucleophilic atom the weaker the nucleophile:

Examples

Good : : Bad

Strength

The strength of a nucleophile is determined by the rate it reacts with an alkyl halide. - A strong nucleophile reacts fast, a poor nucleophile reacts slowly.

Trends

- Negative ions are stronger nucleophiles than neutral ones:

Components

Conditions

| - | Preferred/required | Suitable | Does not work |

|---|---|---|---|

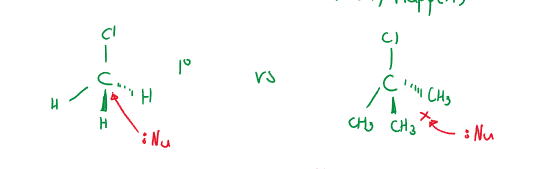

| Substrates | Primary alkyl halide | Secondary alkyl halide (Must be in a polar aprotic solvent) | Tertiary alkyl halide |

| Solvent | Polar aprotic solvent (propanone, ethanenitrile, ethers, acetone, DMF, DMSO, DME) | N/A | Polar protic solvents |

| Nucleophile | Strong nucleophile | N/A | Weak nucleophiles |

| Rate | Step 1: Nu: attacks (slow) Step 2: Leaving group leaves (slow) | N/A | N/A |

| Leaving group | Good leaving group | Poor leaving group | N/A |

Mechanism

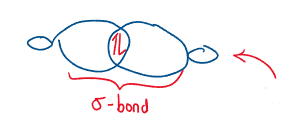

Recall that in an hybridized orbital there is a large lobe where the bond forms and a small lobe on the opposite side (antibonding).

In mechanism, the will attack the backside of the orbital that is bonded to the leaving group.

The carbon temporarily is bonded to both the and the leaving group in a transition state.

In this mechanism, there is an inversion of the molecular configuration.

These reactions happen at different rates for different substrates: , where happens so slowly, it is negligible. This is because substrates have a less electron dense backside, allowing for better attacks.

Examples:

| Preferred/required | Suitable | Does not work | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrates | Tertiary substrate | Secondary alkyl halide (Must be in a polar protic solvent) | Primary alkyl halide |

| Solvent | Polar protic solvent (water, alcohol, carboxylic acid) | / | Polar protic solvents |

| Nucleophile | Strong nucleophile | Weak nucleophiles | / |

| Rate | Step 1: Leaving group leaves (slow) Step 2: Nu: attack (fast) | / | / |

| Leaving group | Good leaving group | / | Poor leaving group |

Steric Hinderance

Bulky alkyl groups makes it very difficult for to attack the electrophiles.

Mechanism

Rate =

Rate =

Rate =

In , an intermediate is formed when the leaving group is in the substrate leave spontaneously. The carbocation intermediate can exist for an observable/significant period of time. The solvent is important for stabilizing both the leaving group and the carbocation

There must be a really good leaving group

This creates a racemic mixture where there is no optical activity.

Leaving Groups

In both and , there is a difference in the rate based on the leaving group.

Bond enthalpies

To compare leaving groups, bond enthalpies indicate the amount of energy required for the leaving group to break off.

- Iodo () = fastest leaving group

- Bromo ()

- Chloro ()

- Flouro () = slowest leaving group

Other leaving groups

Separately, are considered to be excellent leaving groups to poor leaving groups in ascending order.

vs.

When compared to , is considered (by IB*) to be faster because they are ‘unimolecular’ and are only dependent on 1 molecule to occur, whereas requires more than one species.

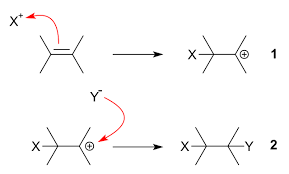

Electrophilic Addition

Reactants are classified as electrophiles or nucleophiles. In general, electrophilic addition is the process of a double bond turning into a single bond with some other diatomic molecule added.

- (electrophile) is attracted to the bond of the alkene.

- The electron in the bond reaches out and creates a covalent bond with the .

- This then breaks the bond between

- Since the and new uses two electrons to forma bond, the other carbon is now electron deficient, turning into a carbocation.

- The carbocation is an extremely attractive electrophilic substance to , nucleophile.

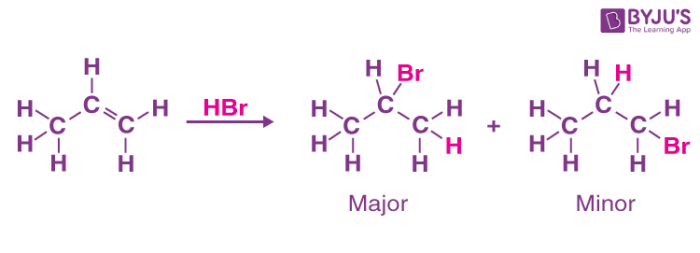

Markovnikov’s Rule

“The thing carbon that has more hydrogens is more likely to bond with the hydrogen of a hydro-halogen. This is because the carbon that is bonded to more electron rich branches tend to be more stable, thus less likely to be a cation.

- This applies to asymmetric reagents and asymmetric alkenes.

- The electropositive part of the reagent bonds to the carbon of the double bond that has a greater amount of hydrogens attached. - The stability of the carbocation intermediate.

- The less saturated carbons, form more stable carbocations, giving the nucleophile a chance to attack the electrophile.

- The inductive effect is where the electron density of the other alkyl chains stabilize the carbocation. Think if this as an orchestra compensating for a missing member, and getting away with it vs. having a missing solo, as in a primary carbon.

The major product is the Markovnikov product, and the Minor product is the Anti-Markovnikov product. The two species produced from electrophilic addition form regiorisomers.

Oxidation and Reduction

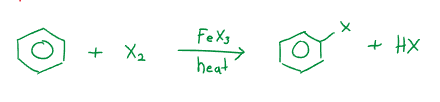

Aromatic Reactions

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

Halogenation reactions involve iron(III) halides, ; and aluminum halides, with heat as catalysts. For example:

Nitration:

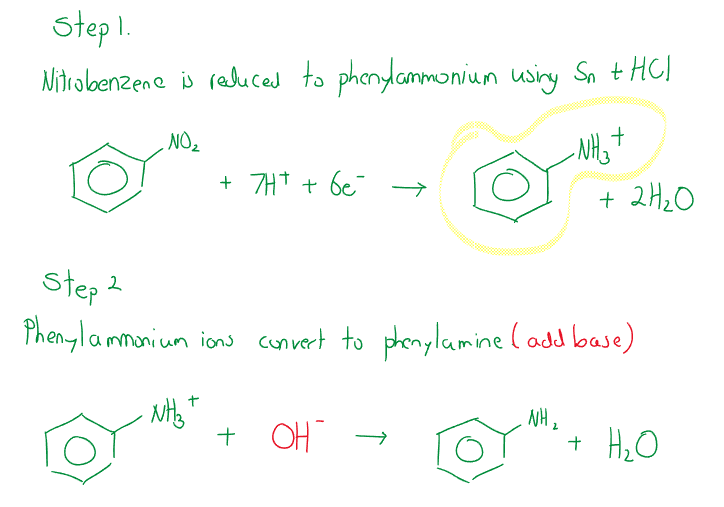

Nitrobenzene to Phenylamine (aniline)

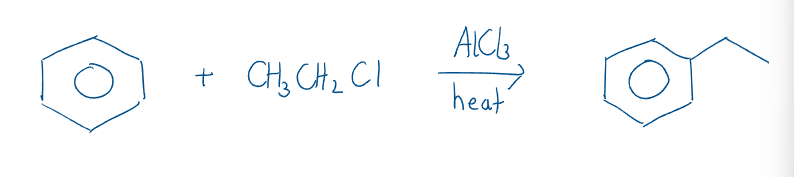

Friedel-Crafts alkylation