2024-07-1616:28 Status:IBnotesCHEM121

Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory

Overview

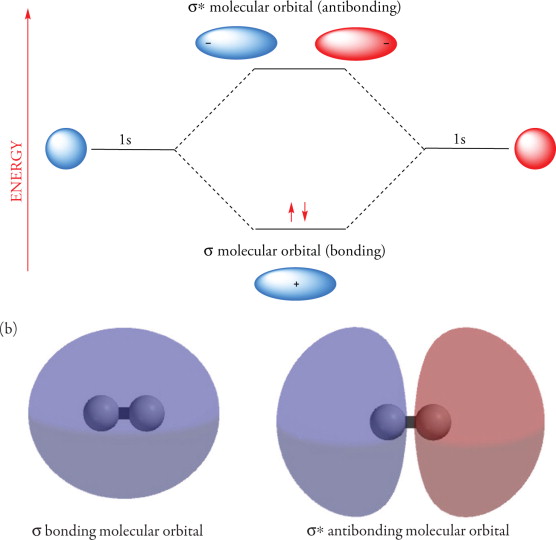

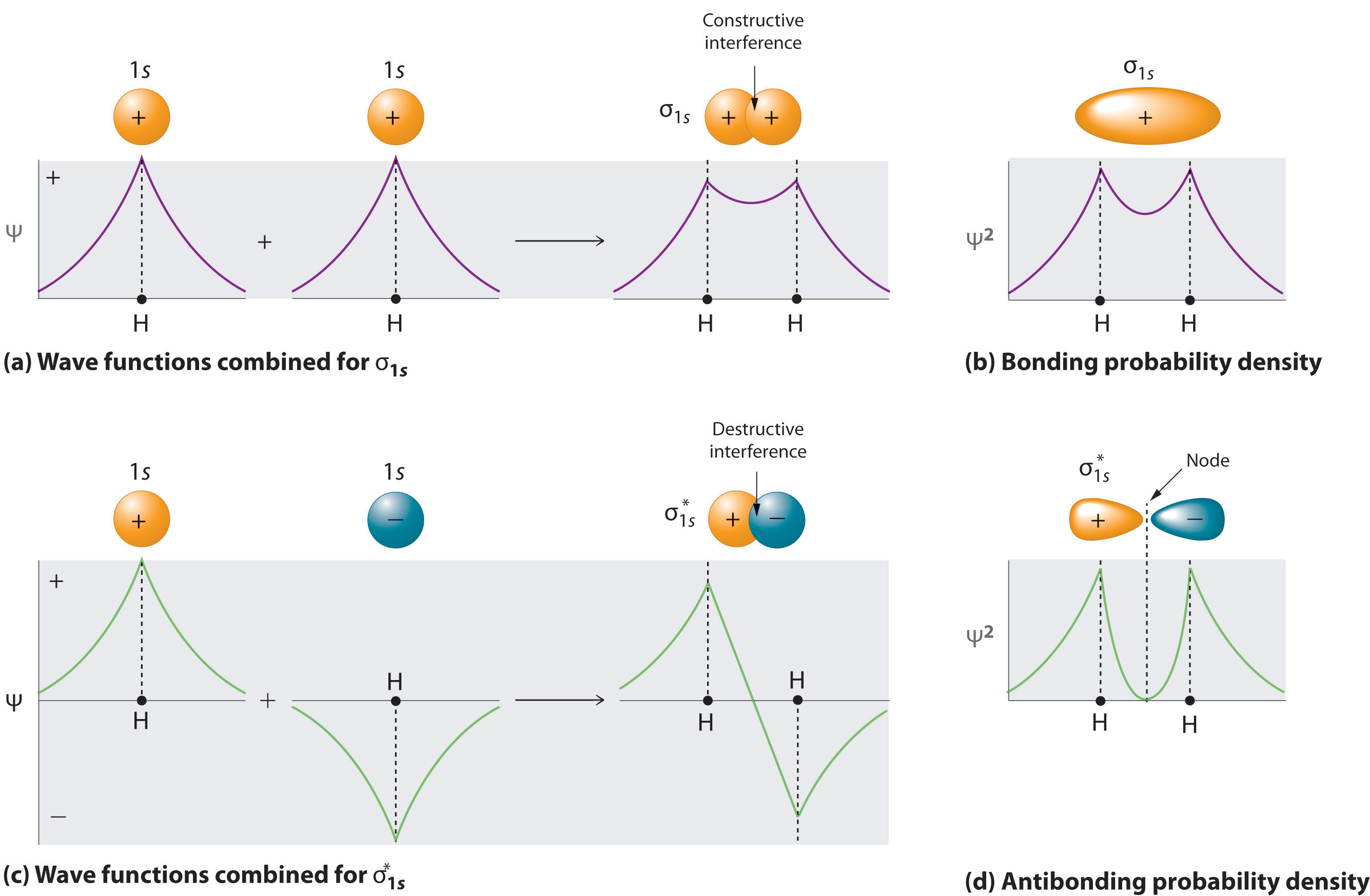

Molecular orbital (MO) wavefunctions describe wave-like behavior of electrons in a molecule as a while. MO wavefunctions can be approximated as the superposition of atomic orbital (AO) wavefunctions with constructive and destructive interference. (VBT is a localized application of MO theory. There are no cases where VBT fails but Lewis/VSEPR are successful).

- The total number of MOs formed is always the same number of AOs. (similar to 5 atoms = 5 nuclei, molecule with 5 atoms has 5 nuclei)

- When two AOs are combined, the resulting bonding MO has fewer nodes.

- The more AOs overlap, the larger the enrgy gap between the resulting bonding and antibonding orbitals.

- Only AOs of similar energy interact significantly (1s and 1s, not 1s and 2s)

Wave Superposition

When waves superimpose, they combine to produce a larger or smaller wave at certain points. As electrons have wavefunctions, this also applies. A covalent bond forms when atomic wavefunctions superimpose and there is increased electron density between the two nuclei. The principle of superposition is used both in VBT and MO theory.

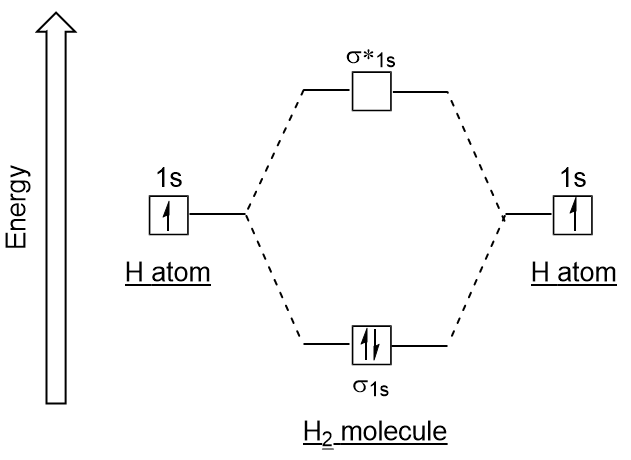

Molecular Orbitals of Molecular Hydrogen ()

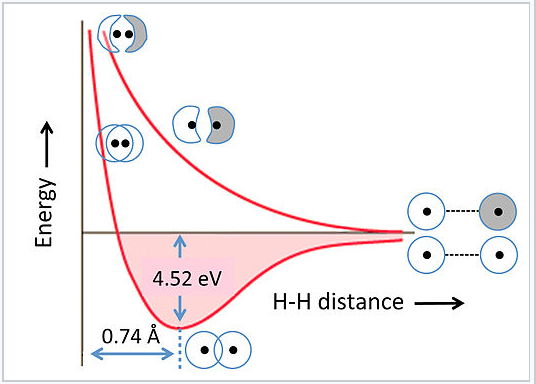

Consider two 1s orbitals on isolated hydrogen atoms. At an infinite distance, the wavefunctions of each hydrogen do not overlap to a significant degree. As the distance between the two decreases (i.e. is formed) there is constructive interference - bonding MO and destructive interference - antibonding MO. In some cases, nodal planes can form between the nuclei in antibonding orbitals.

- Constructive interference of the orbitals lowers energy, and destructive interference raises the energy.

- Orbitals with greater overlap have greater differences in energy between bonding and anti-bonding orbitals.

- Energy in antibonding orbitals increases as the internuclear distance decreases. Energy in bonding orbitals decrease as the internuclear distance decreases.

- There exists a minimum energy at which the average bond distance is = the lowest, most stable energy state.

- The nature of the antibonding MO is only considered for the minimum energy bonding MO. (For )

- Destructive interference leads to a node between the nuclei.

Probability Distribution Functions

Energy Levels of Molecular Orbitals in Hydrogen ()

As molecular orbitals are the overlap of atomic orbitals, MOs, must have specific energies associated with them. When the MOs of are formed, the bonding MO is the lower energy relative to the atomic 1s orbital, and the antibonding orbital is the higher energy.

In general, MOs with more nodes will have higher energies than MOs with fewer nodes.

When constructing an orbital interaction diagram, the electrons of opposite spin occupy the lowest energy orbital first. For , the orbital interaction diagram gives the ground state configuration for (unoccupied orbitals are not written). The overall energy of the two electrons in the orbital is lower than just , thus explaining why elemental hydrogen is instead of .

- calculate the total number of electrons in the atomic orbitals;

- Fill the MOs with the number of electrons calculated in previous step.

- Fill the lowest energy orbitals first (Aufbau principle)

- Place a maximum of 2 spin-paired electrons in each MO (Pauli exclusion principle)

- Place electrons in degenerate MOs singly, with the same spin before pairing them (Hund’s rule)

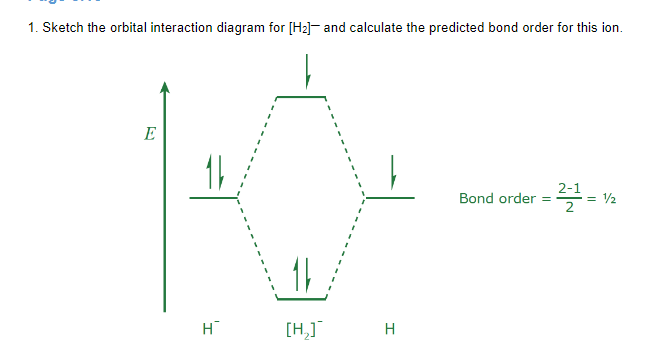

Bond order

MO theory can predict bond order: when electrons occupy bonding orbitals, the bonding interaction between the nuclei is strengthened, and when electrons occupy antibonding orbitals, the attraction is weakened. This explains why bonds of higher order require more energy to break. To find the bond order, Where is the number of electrons in bonding orbitals, and is the number of electrons in antibonding orbitals. To check if a molecule exists, find the bond order using a orbital interaction diagram and see if the bond order is 0

Molecular Orbitals of Second-Row Homonuclear Diatomic Species

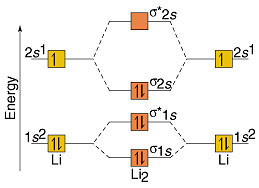

Molecular Orbitals of Dilithium ()

MO electronic configuration:

MO electronic configuration:

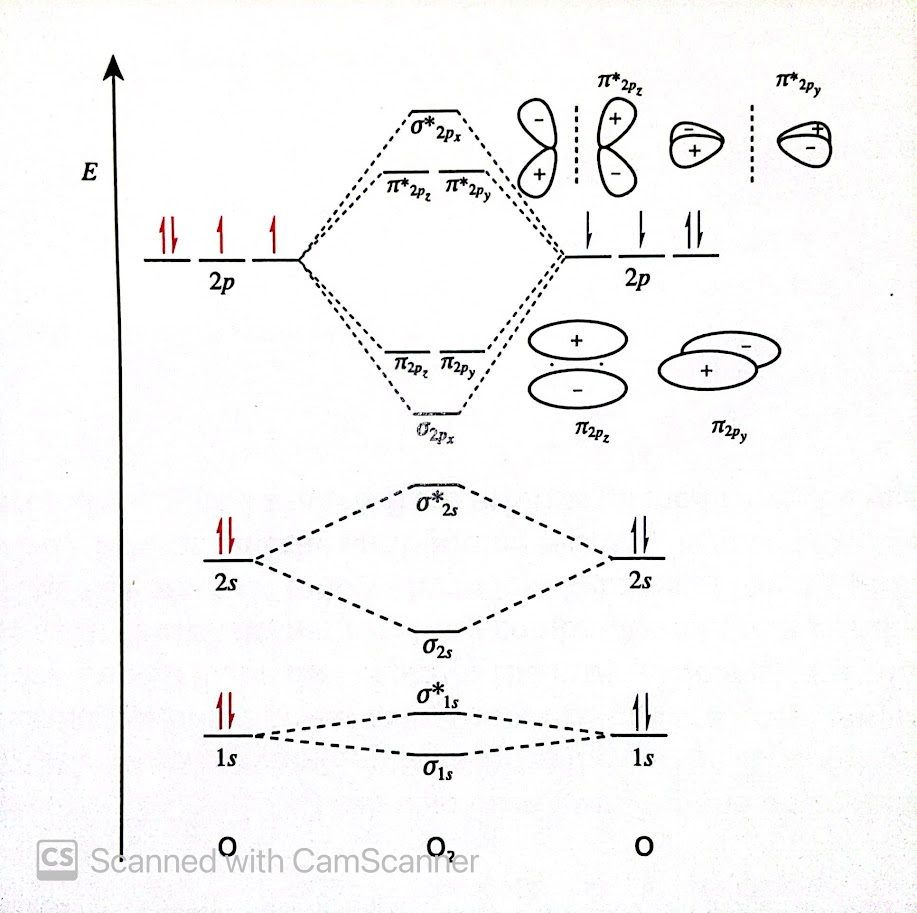

Molecular Orbitals of Dioxygen ()

When two 2p orbitals on adjacent atoms are oriented along the internuclear axis (x-axis), constructive interference occurs on that axis, thus the bonding and antibonding MOs have cylindrical symmetry. The other two nodes are not symmetrical about the axis as there is a nodal plane on the x axis for both. This leads to electron density above and below the axis. Therefore, resulting in and orbitals.

- The and orbitals are degenerate and the and degenerate, but higher energy. This is because the atomic orbitals from which these MOs are derived and are exactly the same other than their orientation. Thus, the MOs are exactly the same other than their orientation.

- The spacing between the and the is smaller than between the and orbitals. This is because the end-to-end overlap between the orbitals is greater than side-to-side overlap of the and the orbitals.

- The spacing between the and orbitals is smaller than the spacing between and orbitals. This is because the 1s orbitals do not overlap with each other as much as the 2s orbitals. The greater the constructive and destructive interference, the greater the energy lowering and raising respectively.

In an orbital interaction diagram, two orbitals are given special names as they play an important role in the chemical behavior and properties of a species. These are the highest energy orbital, highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), and lowest energy orbital, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). The HOMO can be fully occupied or partially occupied, but the LUMO is empty in the ground state.

HOMO in dioxygen = LUMO in dioxygen =

All homonuclear diatomics of the second period have the same MOs as , only the relative energies differ.

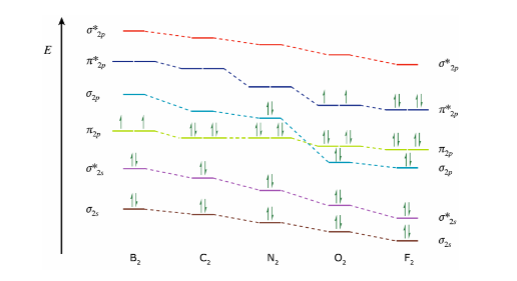

Two important observations need to be made from this graph:

- The MO energy levels decrease from left to right across the period. This experimental fact may be rationalized by the increase in and from boron to fluorine. I.e. the electrons are more strongly attracted to the nucleus.

- Between and , a change in relative energies for the and is observed. The complete explanation is complex but consideration of 2s and 2p orbitals can inform some of the reason: As Z increases, the difference in energy of 2p and 2s increases, however, for smaller differences in 2p and 2s energy levels, the orbitals start mixing. When these two orbitals start “mixing,” the is higher in energy than . This is the case for and .

One electron Atoms and Ions

Background

In a one-electron atom or ion, such as , etc. the negatively charged electron is located somewhere around the positively charged nucleus. The distance between the nucleus and the electron is given by . Where is the potential energy between the electron and the positive nucleus, and are the charges of the respective particles. Additionally, Is the form of the previous equation except the charge of the electron is (always) negative, multiplied by the charge of the nucleus’ charge, . In general, the attraction between two oppositely charged particles is greatest at smaller distances (smaller radial distances) as opposed to larger distances. Given de Broglie wavelength of an electron is comparable to the size of an atom, it must be treated as a wave (thus discarding Bohr’s model of the atom) and obey [Schrödinger’s equation][Basics of quantum mechanics]. This will be what describes the kinetic energy, and potential energy of an electron (with a nucleus).

The spherical model of the atom requires radial coordinates to describe the location of the electron at a given time.

The reason why only one electron is considered for a nucleus is that the Schrödinger equation can only be solved analytically for one-electron atoms and ions (other computer-based methods are used to solve for approximate multielectron atoms/ions position).

Spherical polar coordinates are used to describe wavefunctions with the following: The radial component of the wavefunciton, , depends only on , determining the size of the orbital. Whereas, the , corresponds to the origin and shape of the orbital.

Quantum Numbers ()

The solutions of the Schrödinger equation for the one-dimensional particle-in-a-box could be described with one quantum number, . For one-election atoms and ions, three quantum numbers are needed to solve the wavefunction ().

- is the principle quantum number (1,2,3, … )

- is the angular moment quantum number (for a given takes on all integer values between and ) ()

- is the magnetic quantum number. For

For each value of there are n values of and for each value of there are values of . These restrictions are in place so that the wavefunction is a valid solution of the Schrödinger equation.

Chemists call each value of n a “shell” and each value of "" a subshell. The latter are given these historical labels (for greater values of , the names follow in alphabetic order, i.e. )

| l | subshell |

|---|---|

| 0 | s |

| 1 | p |

| 2 | d |

| 3 | f |

| The principal quantum number and angular momentum quantum number together represent a specific type of orbital (subshell) (1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3d, 3p) | |

| For example when , and , the orbitals are called and . The quantum numbers corresponding to orbitals all in are: |

| n | l | m_l | Number of Orbital |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | -1,0,1 | 3 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| In general, there are a total of orbitals in the shell. | |||

| Similar to Wave-like Behavior Probability, nodes are related to quantum numbers. Nodes can appear in the radial coordinate, r (radial nodes) or in the angular coordinates, (called angular nodes). |

For any given wavefunction,

- the total number of nodes (radial + angular) is

- the number of angular nodes is

Shapes of and orbitals

Recall Wave-like Behavior Probability and that gives the probability distribution for a wavefunction. For atoms, depends on and it is difficult to fully plot in two dimensions. In practice, the only part depending on is plotted.

Radial Probability Distribution

The radial part of the hydrogen atom, wavefunction , depends on the distance from the nucleus, .

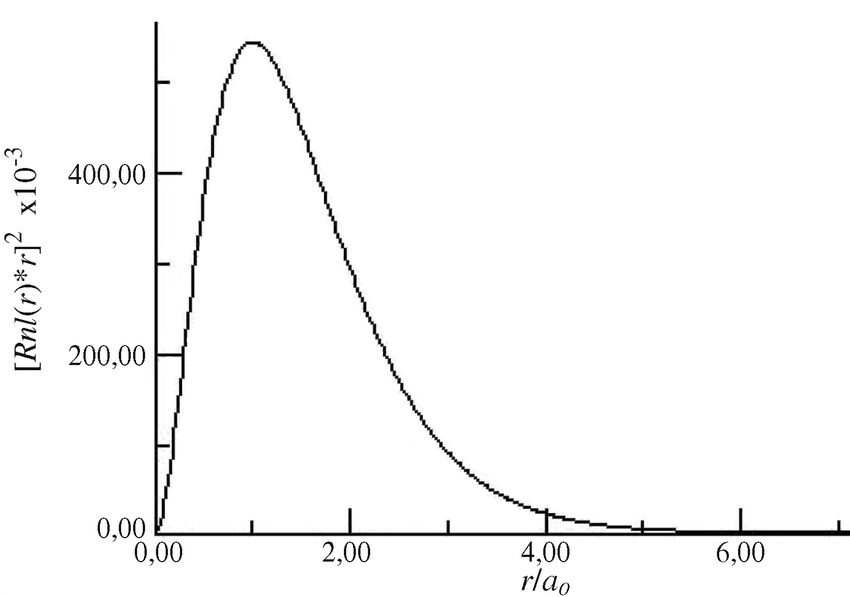

- has the highest value at and decays exponentially as increases. As the angular portion of the orbital is constant, it is spherical, and proportional to

- has the highest value at and decays similarly to . Though may seem to suggest the probability of finding an electron, it does not account for the 3d nature of the atom. In order to take the 3rd dimension into account, the overall probability of finding the electron at ALL possible points at distance must be considered. This is where the surface area of the sphere, is incorporated into

- depicts the probability of finding an electron; the probability is near 0 at the nucleus, and the maximum is at . This is the same value as the Bohr radius, .

Using the analogy of apples falling from a tree, they are very unlikely to fall near the trunk, and most likely to fall at a certain distance from the trunk, and decay from that maximum onwards. Thus, the probability for finding an electron will be the radial probability distribution model (as opposed to .

Orbitals

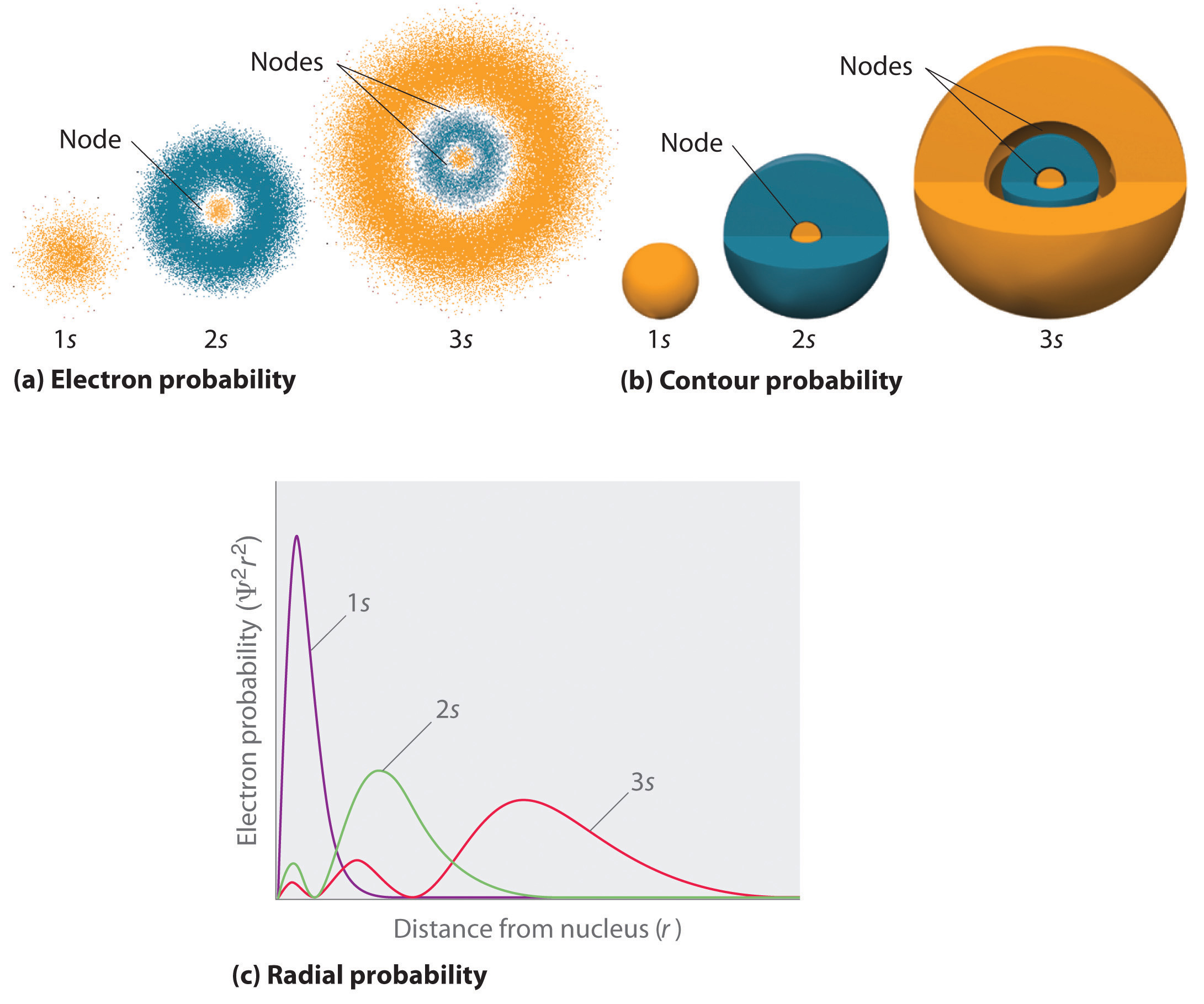

All orbitals have , and therefore no angular nodes. The probability distribution of orbitals varies only with . Which means they are only spherical. The radial probability distribution for the and orbitals are shown below:

The following conclusions from the graph can be taken:

- As increases, the distribution shifts to larger , and the most probable values of increase. This means that, as increases, there is a greater chance of finding the electron further away from the nucleus. However, there is a greater chance of finding an electron closer to the nucleus in increasing (for instance, an electron is more likely to be found closer to the nucleus for a orbital than a orbital)

- The number of radial nodes is , as there is no angular nodes in orbitals. The number of nodes increases as increases.

- The wavefunctions extend to infinity, which mathematically means that they are described as exponential functions that relate and , e.g. . This means that the electron can (theoretically) be found anywhere.

- Far end, and at the nucleus are node considered nodes.

As the charge of the ion increases, the attraction the electron has to the nucleus becomes greater. This means the electron is more likely to be found closer to the nucleus as the charge of the nucleus becomes more positive.

Because the probability distributions go on to infinity, only 90% of the probability distribution is considered.

Orbitals

The three orbitals have , and thus one angular node. Or one plane that separates the positive and negative phase. The equations that describe the orbitals are:

\Psi (p_x) \sim xR(r) \\ \Psi (p_y) \sim yR(r) \\ \Psi (p_z) \sim zR(r) \end{gather}$$ Where the radial term $R(r)$ is an exponentially decreasing function of $r$, and $x,y,z$ are distances along the corresponding Cartesian coordinates of the atom. Thus, the angular node for the $p_x$ orbitals arises where $x,y,z$ are 0 for their respective functions (presented above). The angular nodes are known as nodal planes, as they are planes in the Cartesian coordinate system. ![[Pasted image 20241026220635.jpg]] ![[atomic-orbital-radial-probability-graph-260nw-1639712317.webp]] The figure above shows that these orbitals exhibit the same behavior as $s$ orbitals. However, the sum of the angular and radial nodes implies that each $p$ orbital has $n-2$ radial nodes, (generally increasing with $n$). ![[Pasted image 20241026221332.jpg]] ### $d$ Orbitals The five $d$ orbitals $(d_{xy}, d_{yz}, d_{xz}, d_{x^2-y^2}, d_{z^2})$ have $\ell =2$ and thus two angular nodes. Like $p$ orbitals, the subscript of each $d$ orbital in the set $d_{xy}, d_{yz}, d_{xz}$ give its angular dependence. For example, $\Psi (d_{xy})\sim xyR(r)$, which means this orbital is zero when $x=0$ and when $y=0$ etc. ![[Pasted image 20241026222841.jpg]] The $d_{x^2-y^2}$ wavefunction has the form $\Psi (d_{x^2-y^2}) \sim (x^2-y^2)R(r)$ so the nodes depend on when $x^2 = y^2 \to x=y$. Thus, the planes are diagonal. The final orbital, $z^2$ has **cone shaped angular nodes.** ![[Pasted image 20241026223348.png]] ![[Pasted image 20241026223457.png]] ### Shell Structure of the Atom The radial probability distributions of orbitals in $n=1,2,3$ shells differ, but all orbitals with the same $n$ value have the same maximal probabilities about the same distance from the nucleus. I.e. this predicts that atoms have layered structures. Because some lower shell electrons are closer to the core, they do not participate in chemical reactions for this reason. ![[ByWihr92T4G30tQCrIMY_hy1s.png]] ### Energies of One-electron Atoms and Ions For a one-electron species, the energy of the electron is described by a specific wavefunction with a particular $n, \ell$ and $m_{\ell}$ given by: $$E_n = -2.18 \times 10^{-18} J\left( \frac {Z^2}{n^2} \right)$$ Where $Z$ is the periodic number, $n$ is the principle quantum number, and $-2.18\times 10^{-18}J$ is the Rydberg constant. Notice that all electrons on the same shell level have the same energy as $\ell$ and $m_{\ell}$ are unaccounted for. This is an example of degeneracy (multiple states with the same energy level) The value $E=0$ corresponds to the electron separated at an infinite distance from the nucleus, which is considered to be ionized. The equation given is negative, which suggests that it is energetically favorable to have the electron bound to the nucleus. ## Hybrid(ized) orbitals + overview of VBT #### Overview - textbook > When thinking of electrons as particles, representing bonds as dots or lines makes sense, however, once they are expressed as waves, new definitions of bonds are needed. This is where hybridized orbitals provide some clarity: if electrons can be represented as a wave, then superimposing them would result in a new region being formed. If the waves are constructive, the region formed is a covalent bond; if there is destructive interference, then there is a node (a region where the likelihood of an electron being in that region is 0). Hybrid orbitals are only formed in bonding. They take the intermediate energy between s and p orbitals. The shape of the hybridized orbital is still a probability function. #### Assumptions made for VBT Large molecules have hybridization of different orbitals and thus more complex than simpler models can accurately capture. For this reason, the following approximations are made: 1. Each covalent bond is treated individually - this excludes resonance: in which case, MO theory will have to be used to treat $\pi$ bonds as delocalized. 2. VBT covalent bonds are formed by overlap of half-filled orbitals in the valence shell of each atom (each contributing 1 electron). - Inner electrons are ignored. 3. Because of 2, the bonding/antibonding MO pair will only contain 2 electrons as only the bonding MO has electrons in it (constructive wavefunction). #### Expressing bonds in VBT + Ambiguity - Diatomic molecules such as $H_2$ MO: $\sigma_{1s^2}$ vs. VBT: $\sigma(1s-1s)$. - VBT predicts that $O_2$, MO: $\sigma_{1s^2}\sigma_{1s^2}^*\sigma_{2s^2}\sigma_{2s^2}^2\sigma_{2p^2}\pi_{2p^4}\pi_{2p^2}^*$ either has two $\pi$ bonds ($\pi(2p_y-2p_y), (\pi(2p_y-2p_y))$) or a sigma bond $\sigma(2p_x - 2p_x)$ and a $pi bond$, $\pi(2p_x-2p_x)$. Both of these options are inconsistent with bonding MO theory, and don't predict the existent of two unpaired electrons. = VBT is an approximation, so prefer the forming of $\sigma$ bonds over $\pi$ bonds for greater energy stabilization. #### Hybridized Orbitals Take $CH_4$. According to VBT, carbon only has two unpaired electrons in its $2p$ orbitals. This would imply that $CH_2$ is a stable molecule, but methane, $CH_4$ is more commonly seen. The reason why this method fails here is that it does not consider neighboring atoms disrupting the form of atomic orbitals. To resolve this inconsistency, mixing the orbitals of hydrogen and carbon superimpose the electron wavefunctions, thus creating a new, hybridized orbital. for $CH_4$ the following is formed: ![[Pasted image 20241122215811.png]] For each atomic orbital hybridized, one hybrid orbital is formed. There are "only 5 relevant hybrid orbitals" ##### $sp$ Hybridization Scheme - Take the hybridization of a $2s$ and a $2p_x$ orbital = 2 $sp$ orbitals. - Two hybridized orbitals, → Linear = $180 \degree$ - Each $sp$ orbital has one large lobe and a small lobe (the large lobe tends to be written as the positive phase but its arbitrary) - Energy of the $sp$ orbital is about half way between $2s$ and $2p$. ![[Pasted image 20241122220734.png]] ![[Pasted image 20241122221322.png]] ##### $sp^2$ Hybridization Scheme - Mixing the $2s, 2p_y$, and $2p_x$ orbitals = 3 $sp^2$ orbitals - None of the orbitals are directed in the $z$ axis, so they lie in the $xy$ plane - The orbitals are $120\degree$ from each other - The orbitals have about 3/4th the between $2s$ and $2p$ - Both the hybridized and unhybridized orbital splay an important role in bonding: the availability of of an unhybridized $2p$ orbital allows for multiple bonds to be formed - higher than degree 1, with a $sp^2$ orbital. ![[Pasted image 20241122222623.jpg]] ![[Pasted image 20241122222609.png]] DO NOT FORGET that the remaining $2p_z$ orbital exists. It's just not hybridized. ##### $sp^3$ Hybridization Scheme - Mixing $2s,2p_x, 2p_y$ and $2p_z$ orbitals = 4 $sp^3$ orbitals. - Tetrahedral. - Any 2 of the hybridized orbitals will lie in the same plane at the same time. ![[Pasted image 20241122223642.png]] ![[Pasted image 20241122223801.png]] - This is Carbon's energy hybridization ##### $sp^3d$ & $sp^3d^2$ Hybridization Schemes - Trigonal bipyramidal = $sp^3d$, - Octahedral = $sp^3d^2$ - Only occur in $n=3$ or higher. ##### Procedure for Application of VBT to Molecules with Hybridized Atoms 1. Draw Lewis 2. Determine VSEPR 3. Match hybridization to VSEPR bond angles ## Types of Hybrid Orbitals ### Linear Orbitals ($sp$ Hybridization) Linear orbitals have $sp$ hybridization. These orbitals allow for two bonding sites, and have a linear geometry. In $sp$ hybridization, there is often a triple bond. This often creates 2 $\pi$ bonds as a triple bond creates a linear chain of the bonded carbons. ![[643.jpg]] ### Trig. Planar Orbitals ($sp^2$ Hybridization) Trigonal planar orbitals have $sp^2$ hybridization. These orbitals allow for three bonding sites, and have a trigonal planar geometry. In 1,1,2,2-tertamethylethene, the sigma double bond between $C=C$ brings together the hydrogen attached to both carbons involved. This proximity creates a $\pi$ bond. → Pi bonds ![[reds.png]] ### Tetrahedral Orbitals ($sp^3$ Hybridization) Tetrahedral orbitals have $sp^3$ hybridization. These orbitals allow for four bonding site, and have a tetrahedral geometry. For this kind of hybridization, there are four possible orbital. Methane, $CH_4$ for example, has 4 $sp^3$ orbitals. Typically, carbon can only have two bonds, but with the introduction of the $sp^3$ orbital, the two electrons in the $2s$ orbital go to two of the empty $sp^3$ orbitals. The energy level of this orbital is between that $2p$ orbital’s and the $2s$ orbital’s. This creates 4 bonding orbitals with 25% s character (1:3=1/4 of the orbitals are $s$orbitals) and 75% $p$ character (3:1=3/4 of the orbitals are $p$. So the overall energy level is 75% the way to $p$ from $s$. ![[poihgf.png]] ![[f-d_9782b8d61b4c527b0aa301411399f745015afda8be04856670ce6f87+IMAGE_TINY+IMAGE_TINY.png]] ## Sigma ($\sigma$) & Pi ($\pi$) Bonds ### Sigma Bonds Sigma bonds are covalent bonds and have end-to-end overlapping orbitals. To describe the bonding of the $H-C$ in $CH_4$, take the orbital of the hydrogen, $s$, put a dash between it and the hybridized $C$ orbital, $sp^3$: $H-C$= $s-sp^3$. ![[[poor.jpg]] ### Pi Bonds Pi bonds are created when a sigma bond brings 2 lobes of electron density together; creating an axis that would overlap above. For a side by side view, there would be an overlap of 2-unhybrydized p-orbitals. close together. In 1,1,2,2-tertamethylethene, the sigma double bond between $C=C$ brings together the hydrogen attached to both carbons involved. This proximity creates a $\pi$ bond. - Double bonds = $1\sigma + 1\pi$ - Triple bonds = $1\sigma + 2\pi$ ![[7d0a3cedcde70e5298739462befded02.jpg]] ### Delocalized $\pi$ bonds A delocalized $\pi$ bond is a bond that is spread across 3 or more atoms (each of these atoms must have an unhybridized $p$ orbital). For example: Benzene has a delocalized $\pi$ bond above and below because each carbon has delocalized $p$ orbitals. In resonance structures, the $\pi$ bond is delocalized because it is perpetually moving between single bonds. This is true for resonance structures e.g. Ozone, $O_3$ ![[Delocalization_2.jpg]] ![[sdfghjk.png]] ![[Chem.jpg]]